Unit 3 - Notes

INT242

Unit 3: Secure Cloud Network Architecture, Resiliency, and Vulnerability Management

1. Cloud Infrastructure Security

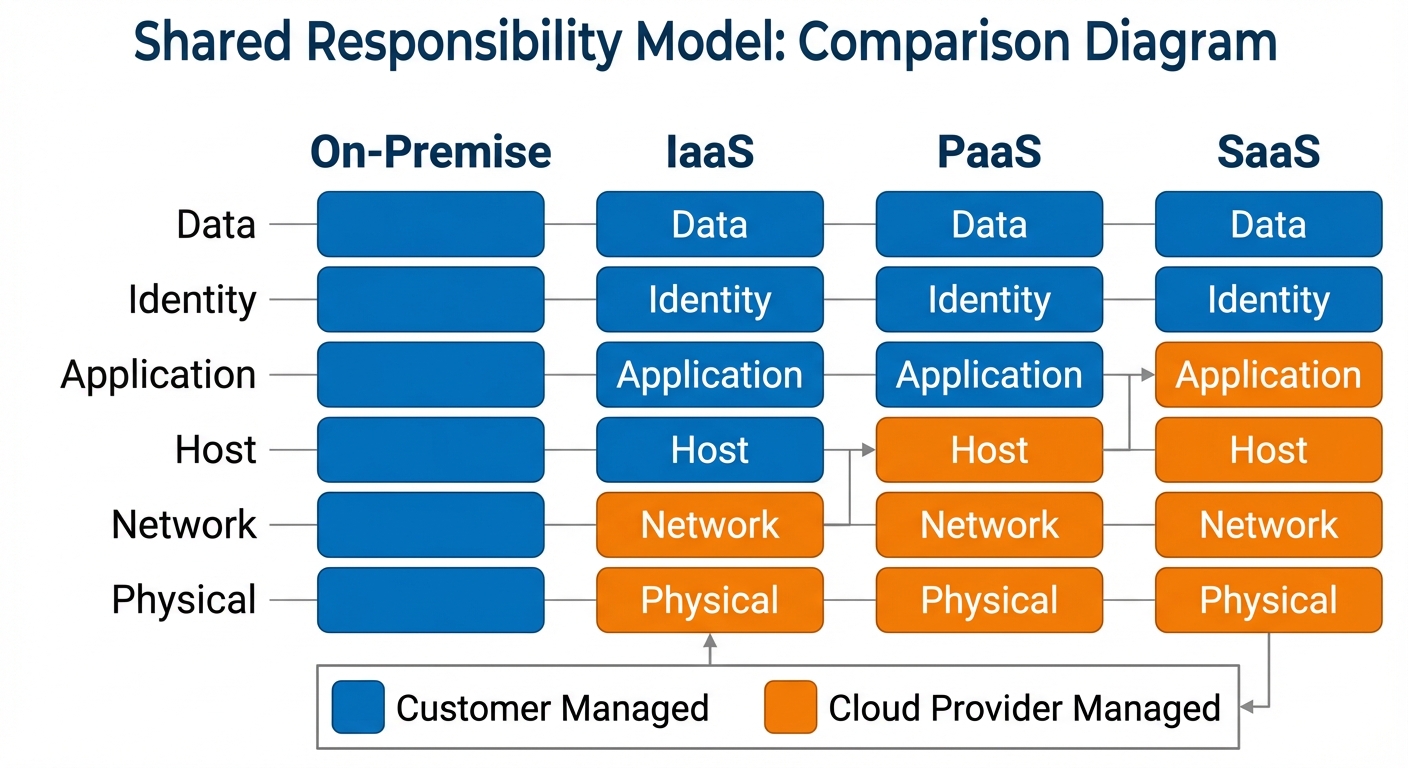

Cloud infrastructure shifts security responsibilities from a purely on-premise model to a shared model between the provider and the customer. Understanding the architecture is prerequisite to securing it.

1.1 Cloud Service Models

- IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service): The provider manages virtualization, servers, storage, and networking. The customer manages the OS, middleware, runtime, data, and applications (e.g., AWS EC2, Azure VMs).

- PaaS (Platform as a Service): The provider manages the underlying infrastructure and the runtime environment. The customer manages data and applications (e.g., Google App Engine, Heroku).

- SaaS (Software as a Service): The provider manages everything including the application. The customer only manages configuration and access (e.g., Microsoft 365, Salesforce).

1.2 The Shared Responsibility Model

Security obligations vary based on the service model. In on-premise, the customer owns the entire stack. In the cloud, security is a partnership.

1.3 Secure Cloud Network Architecture Concepts

- Virtual Private Cloud (VPC): A logically isolated section of the cloud where customers can launch resources in a virtual network they define.

- Security Groups: Acts as a virtual stateful firewall for instances (VMs) to control inbound and outbound traffic.

- Network Access Control Lists (NACLs): An optional layer of security for the VPC that acts as a stateless firewall for controlling traffic in and out of one or more subnets.

- East-West Traffic: Traffic moving laterally between servers within a data center (needs micro-segmentation).

- North-South Traffic: Traffic entering or leaving the data center (typically protected by edge firewalls).

2. Embedded Systems and Specialized Architecture

Embedded systems are computing systems designed for specific tasks, often with real-time computing constraints. They pose unique security challenges due to limited processing power and infrequent update cycles.

2.1 Types of Embedded Systems

- IoT (Internet of Things): Consumer or industrial devices connected to the internet (smart thermostats, cameras). Often lack robust security defaults.

- SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition): Systems used to control industrial processes (power grids, water treatment). High availability is the priority over confidentiality.

- ICS (Industrial Control Systems): The umbrella term for SCADA and Distributed Control Systems (DCS).

- SoC (System-on-Chip): An integrated circuit that integrates all components of a computer or other electronic systems (Raspberry Pi, Mobile phones).

2.2 Security Constraints and Risks

- Resource Constraints: Limited battery and CPU make standard encryption (AES-256) or heavy antivirus agents difficult to implement.

- Patching Difficulties: Many embedded devices have "hard-coded" firmware that cannot be updated remotely, or the vendor ceases support quickly.

- Lifecycle Management: Industrial systems are often designed to last 20+ years, while the OS they run on (e.g., Windows XP Embedded) becomes obsolete in 5-10 years.

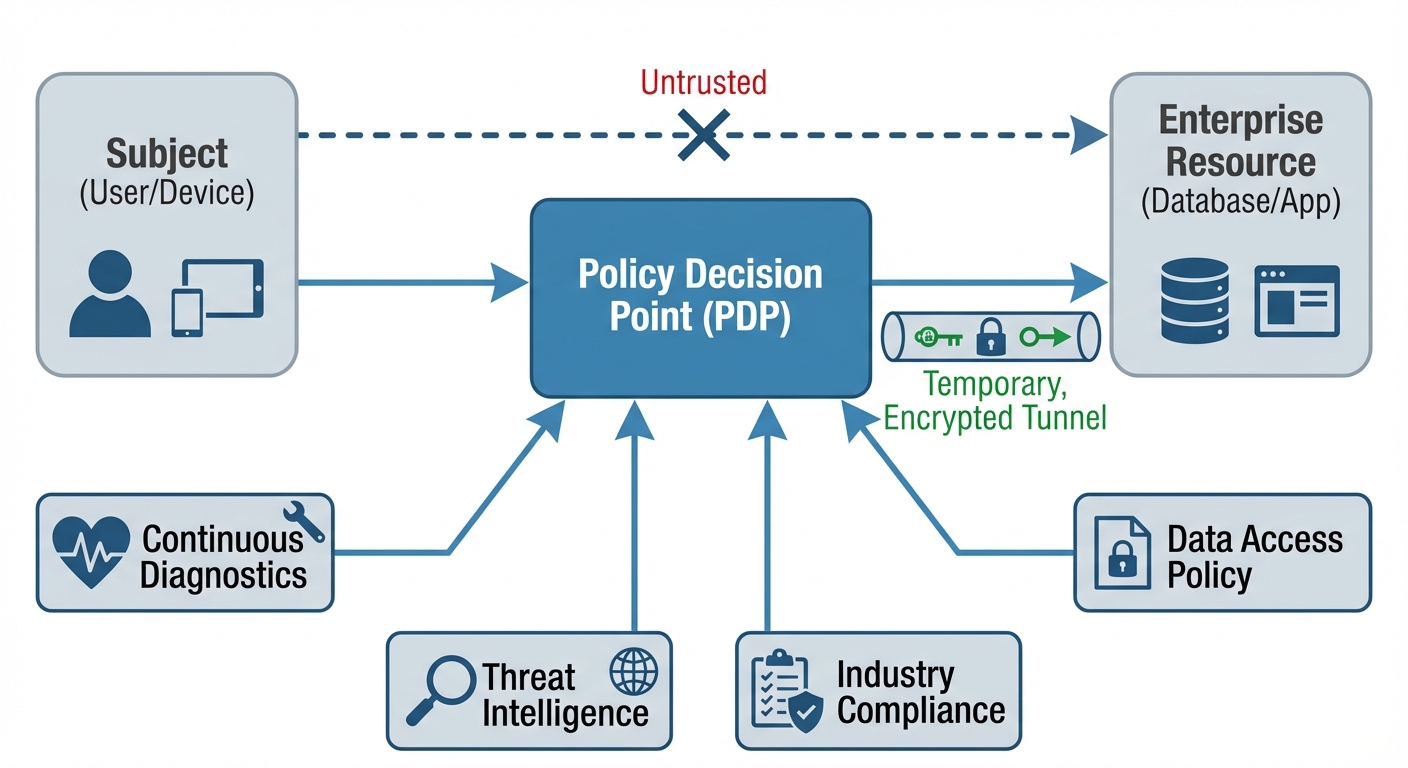

3. Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA)

Zero Trust is a strategic initiative that eliminates the concept of trust based on network location. The core mantra is "Never Trust, Always Verify."

3.1 Core Principles

- Verify Explicitly: Always authenticate and authorize based on all available data points (identity, location, device health, service classification).

- Use Least Privilege Access: Limit user access with Just-In-Time and Just-Enough-Access (JIT/JEA), risk-based adaptive polices, and data protection.

- Assume Breach: Minimize blast radius and segment access. Verify end-to-end encryption and use analytics to get visibility.

3.2 Implementation Components

- Micro-segmentation: Breaking the network into small zones to maintain separate access for separate workloads.

- Identity and Access Management (IAM): The foundation of Zero Trust. Use Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) and Single Sign-On (SSO).

- Software-Defined Perimeter (SDP): Hides internet-connected infrastructure so external parties and attackers cannot see it.

4. Asset Management and Physical Security

You cannot secure what you do not know you have. Asset management is the foundation of vulnerability management.

4.1 Asset Management

- Inventory Management: Maintaining an accurate, real-time list of all hardware (servers, laptops, IoT) and software (OS, applications, licenses).

- Asset Tagging: Applying physical barcodes or RFID tags to hardware for tracking.

- Lifecycle Management: Managing an asset from procurement -> deployment -> maintenance -> retirement -> disposal (sanitization).

4.2 Physical Security Controls

- Perimeter Security: Fencing, lighting, bollards (to stop vehicles), and guards.

- Internal Security:

- Mantraps: A small room with two doors where the first must close before the second opens, preventing "tailgating."

- Biometrics: Fingerprint, retina, or iris scanners for high-security areas.

- Faraday Cages: Enclosures used to block electromagnetic fields (preventing wireless signal leakage).

- Environmental Controls: HVAC (temperature/humidity control) and Fire Suppression (using inert gases like FM-200 rather than water for server rooms).

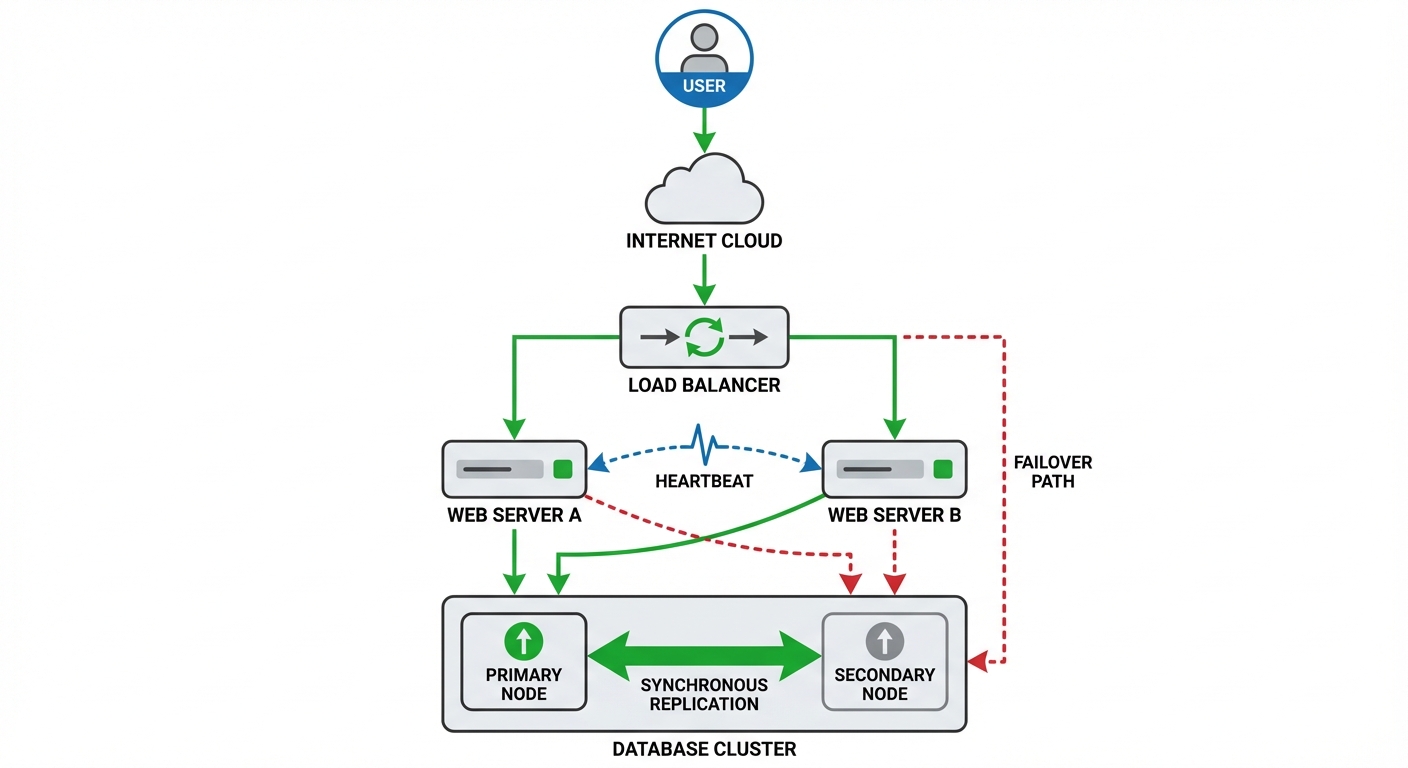

5. Resiliency and Redundancy Strategies

Resiliency is the ability of a system to endure and recover from failures. Redundancy is the method of duplication used to achieve resiliency.

5.1 Storage Redundancy (RAID)

- RAID 0 (Striping): Data split across drives. Fast performance, zero redundancy. If one drive fails, all data is lost.

- RAID 1 (Mirroring): Data duplicated on two drives. High redundancy, higher cost.

- RAID 5 (Striping with Parity): Requires minimum 3 drives. Data and parity information striped. Can withstand 1 drive failure.

- RAID 10 (1+0): A stripe of mirrors. Combines speed and redundancy but requires minimum 4 drives.

5.2 Power and Network Redundancy

- UPS (Uninterruptible Power Supply): Battery backup for short-term power outages/spikes.

- Generators: Long-term power backup (diesel/gas).

- NIC Teaming: Grouping multiple network interface cards to act as one for failover and increased bandwidth.

5.3 Geographic Redundancy (Disaster Recovery Sites)

- Hot Site: Fully operational site with real-time data replication. Near-instant failover. Most expensive.

- Warm Site: Partially equipped (hardware/network ready), but data requires restoration from backups. Recovery takes hours/days.

- Cold Site: Basic infrastructure (power/cooling) only. No hardware or data installed. Cheapest, but recovery takes weeks.

6. Vulnerabilities: Device, OS, Application, and Cloud

A vulnerability is a weakness in a system that can be exploited by a threat actor.

6.1 Device and OS Vulnerabilities

- Buffer Overflow: An application writes more data to a block of memory (buffer) than it is allocated, potentially overwriting adjacent memory and allowing code execution.

- Firmware Vulnerabilities: Outdated BIOS/UEFI can allow boot-level malware (Rootkits).

- End-of-Life (EOL) Systems: Operating systems that no longer receive security patches (e.g., Windows 7).

6.2 Application and Cloud Vulnerabilities

- Injection (SQLi): Malicious SQL statements are inserted into entry fields (e.g., login forms) for execution.

- Broken Access Control: Users acting outside of their intended permissions.

- Misconfiguration (Cloud): The #1 cause of cloud breaches. Examples: S3 buckets left public, default administrative passwords, open management ports (RDP/SSH) to the internet.

- API Vulnerabilities: Unsecured Application Programming Interfaces allowing unauthorized data scraping or logic manipulation.

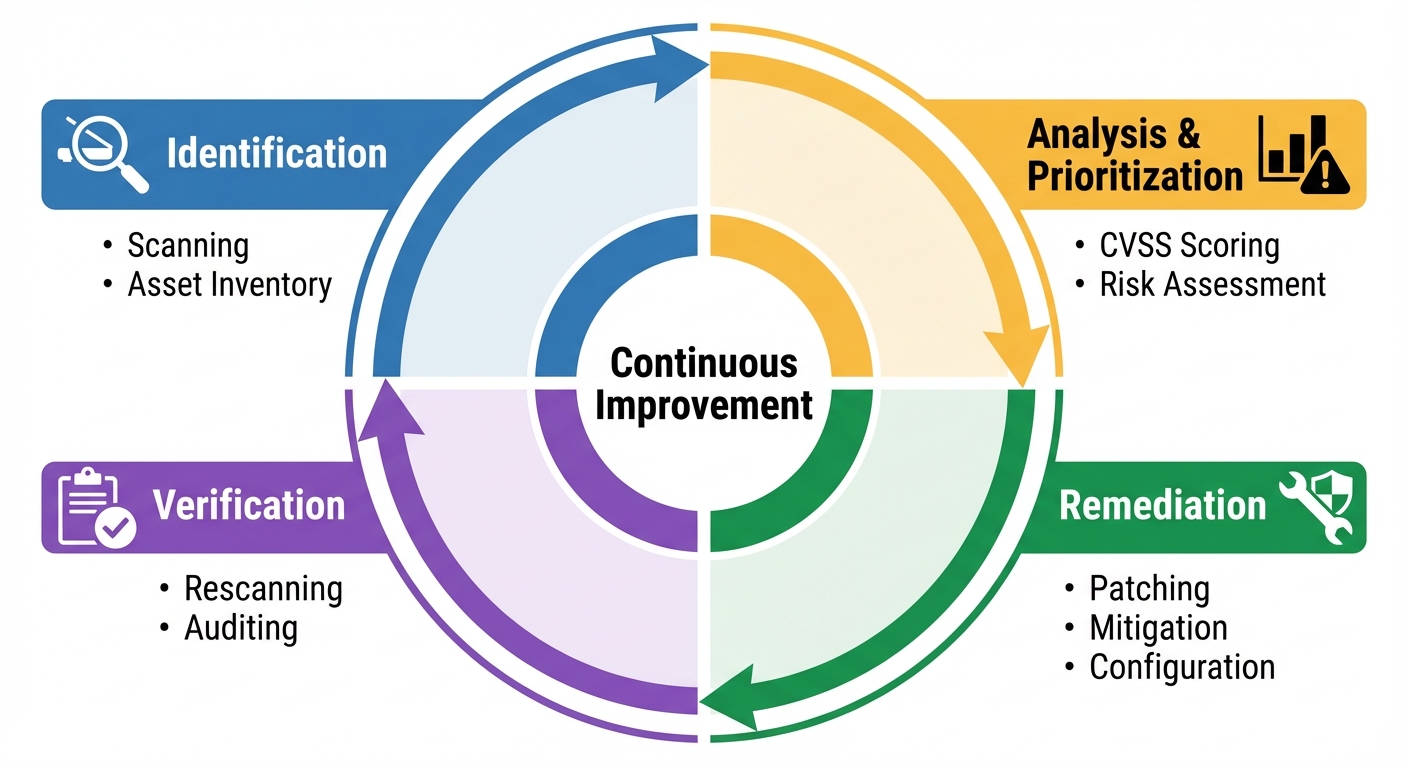

7. Vulnerability Management: Identification, Analysis, and Remediation

Vulnerability management is the cyclical practice of identifying, classifying, remediating, and mitigating vulnerabilities.

7.1 Vulnerability Identification Methods

- Credentialed Scan: The scanner logs into the device with admin rights. Provides deep visibility into missing patches, registry settings, and configuration issues.

- Non-Credentialed Scan: The scanner looks at the device from the "outside." Identifies open ports and banners but misses internal flaws.

- Penetration Testing: Simulating a cyberattack to exploit vulnerabilities (Active assessment vs. Passive scanning).

7.2 Vulnerability Analysis

Once vulnerabilities are found, they must be ranked.

- CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System):

- Base Score: Intrinsic qualities (Attack Vector, Complexity, Privileges Required).

- Temporal Score: Characteristics that change over time (Exploit Code Maturity, Remediation Level).

- Environmental Score: Specific to the user's environment (Asset value, Impact).

- False Positives: The scanner reports a vulnerability that does not exist.

- False Negatives: The scanner fails to report a vulnerability that does exist (more dangerous).

7.3 Remediation Strategies

- Patching: Applying the vendor-supplied update to fix the code (Preferred).

- Mitigation/Workaround: Implementing a control to reduce risk if patching isn't possible (e.g., blocking a port via firewall, disabling a service).

- Acceptance: Management signs off on the risk because the cost of fixing outweighs the risk of exploitation.