Unit 2 - Notes

CSE325

Unit 2: Shell Scripting

1. Script Creation, Execution, and Permissions

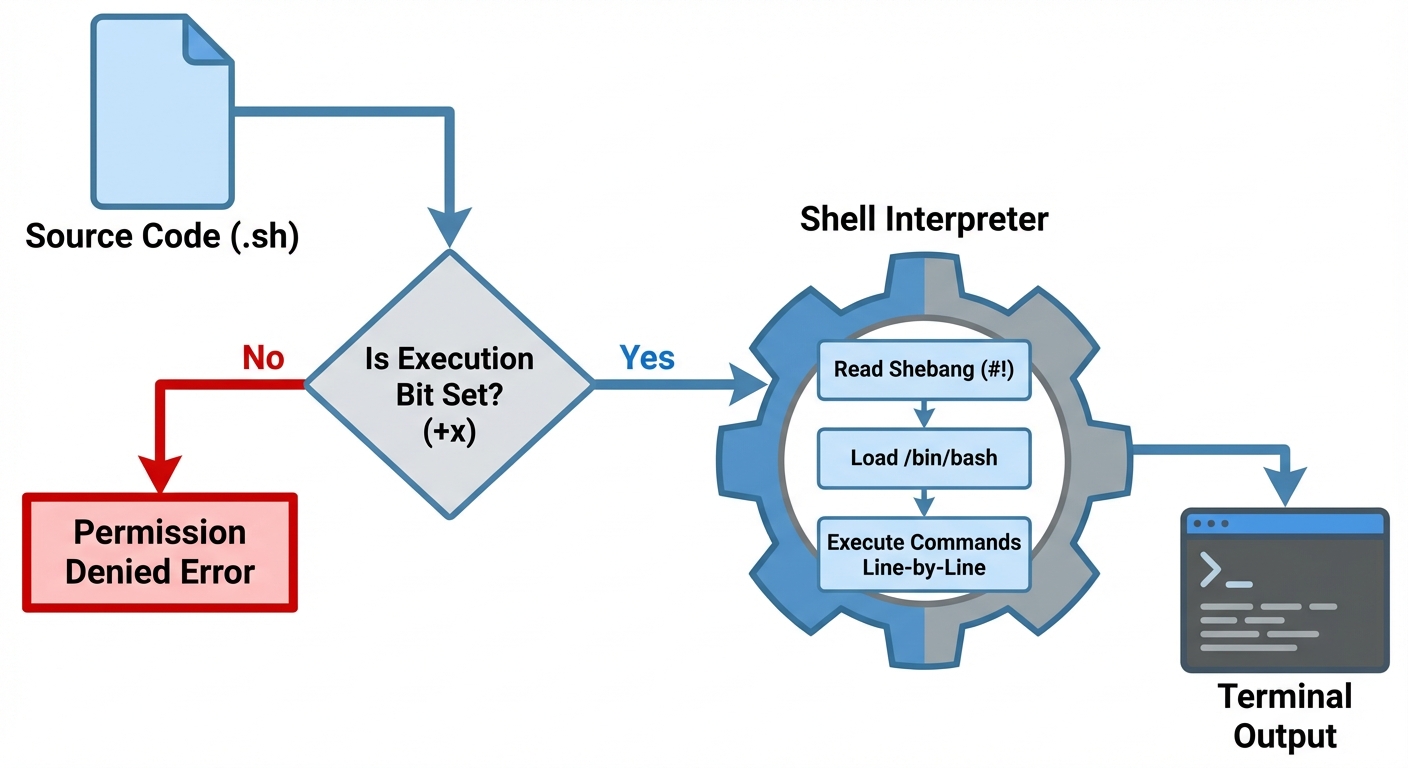

Shell scripting allows users to automate sequences of commands by storing them in a text file. The shell (command-line interpreter) reads the file and executes the commands.

1.1 The Shebang (#!)

Every shell script should begin with a "shebang" line. This tells the system which interpreter to use to parse the script.

- Format:

#!/path/to/shell - Standard Bash Shebang:

#!/bin/bash - Standard Sh Shebang:

#!/bin/sh

1.2 Creating and Saving

- Open a text editor (vi, nano, gedit).

- Write the commands.

- Save the file with a

.shextension (convention only, not mandatory for execution).

Example:

#!/bin/bash

# This is a comment

echo "Hello, Operating System Lab!"

1.3 Execution Modes

There are two primary ways to run a script:

- Direct Execution (Requires Permissions):

BASH./scriptname.sh - Using the Interpreter (bypasses permission check):

BASHbash scriptname.sh sh scriptname.sh

1.4 File Permissions (chmod)

By default, created files are usually read/write but not executable. To run a script directly (./script.sh), you must change its mode.

Symbolic Mode:

chmod +x script.sh(Adds execute permission for everyone)chmod u+x script.sh(Adds execute permission for the User/Owner only)

Numeric (Octal) Mode:

chmod 755 script.sh(rwx for owner, rx for group, rx for others)chmod 700 script.sh(rwx for owner only)

2. Environment and User-Defined Variables

Variables in Bash are typeless (treated as strings) and do not require declaration before use (unless using arrays).

2.1 User-Defined Variables

- Definition:

variable_name=value(NO spaces around the=) - Access:

variable_name - Rules: Case sensitive, usually uppercase by convention.

Example:

#!/bin/bash

name="John Doe"

age=25

echo "Student Name: $name"

echo "Age: $age"

2.2 Environment Variables

These are system-wide variables available to all child processes of the shell. They control the behavior of the system.

Common Environment Variables:

$HOME: Path to current user's home directory.$PATH: Colon-separated list of directories to search for commands.$USER: Current logged-in username.$SHELL: Path to the current shell.$PWD: Present Working Directory.

Exporting Variables:

To make a local variable available to child scripts/processes:

export MY_VAR="Value"

3. Arithmetic Operations using expr and bc

Bash treats variables as strings by default. Specific tools are needed for mathematical calculations.

3.1 Using expr

expr is an external utility used for integer arithmetic.

- Syntax:

expr op1 operator op2 - Crucial Rule: Spaces are mandatory between operands and operators.

- Escaping: Multiplication

*must be escaped as\*.

Example:

a=10

b=20

sum=`expr $a + $b` # Backticks for command substitution

mul=$(expr $a \* $b) # $() notation is preferred over backticks

echo "Sum: $sum, Product: $mul"

3.2 Using bc (Basic Calculator)

expr cannot handle floating-point numbers. bc is an arbitrary precision calculator language.

- Syntax:

echo "expression" | bc - Scale: Used for division to specify decimal precision.

Example:

a=10.5

b=2.5

# Addition

res=$(echo "$a + $b" | bc)

# Division with precision

div=$(echo "scale=2; 10 / 3" | bc)

echo "Result: $res, Division: $div"

4. Input/Output Redirection and Pipes

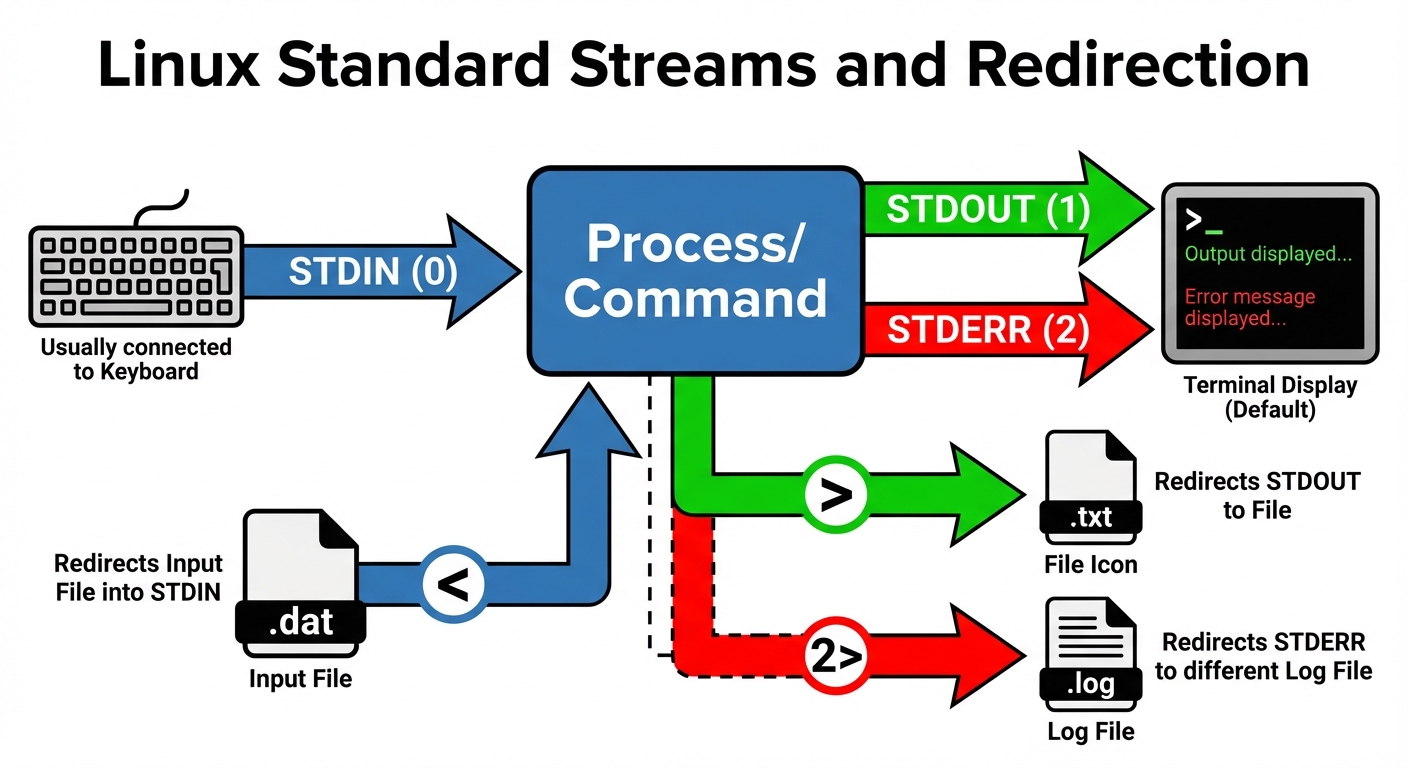

Linux treats input and output as streams of characters.

4.1 Standard Streams

- stdin (0): Standard Input (default: Keyboard)

- stdout (1): Standard Output (default: Terminal Screen)

- stderr (2): Standard Error (default: Terminal Screen)

4.2 Redirection Operators

>: Overwrite output to a file (ls > file.txt).>>: Append output to a file (echo "Log" >> log.txt).<: Input from a file (wc -l < file.txt).2>: Redirect error messages (gcc prog.c 2> error.log).&>: Redirect both stdout and stderr.

4.3 Pipes (|)

Pipes connect the STDOUT of one command to the STDIN of the next command.

Syntax: command1 | command2

Example:

# List files, filter for 'txt', and count lines

ls -l | grep ".txt" | wc -l

5. Conditional Statements and Menu-Driven Programs

5.1 Test Conditions

Bash uses the test command or brackets [ ] for evaluation.

- Numeric:

-eq(equal),-ne(not equal),-gt(greater than),-lt(less than). - String:

=(equal),!=(not equal),-z(string is null). - File:

-f(is file),-d(is directory),-r(readable),-x(executable).

5.2 if-else Construct

if [ condition ]; then

# commands

elif [ condition ]; then

# commands

else

# commands

fi

Note: Spaces inside brackets

[ b ] are mandatory.

5.3 case Statement (Menu-Driven)

Used for multiple choice scenarios (like switch-case in C).

Example: Menu Driven Calculator

echo "1. Add"

echo "2. Subtract"

read -p "Enter choice: " ch

case $ch in

1) echo "Addition selected" ;;

2) echo "Subtraction selected" ;;

*) echo "Invalid choice" ;;

esac

6. Looping Constructs

6.1 for Loop

Used to iterate over a list of items or a range.

Syntax 1 (List):

for i in 1 2 3 4 5

do

echo "Number: $i"

done

Syntax 2 (C-Style):

for (( i=1; i<=5; i++ ))

do

echo "Counter: $i"

done

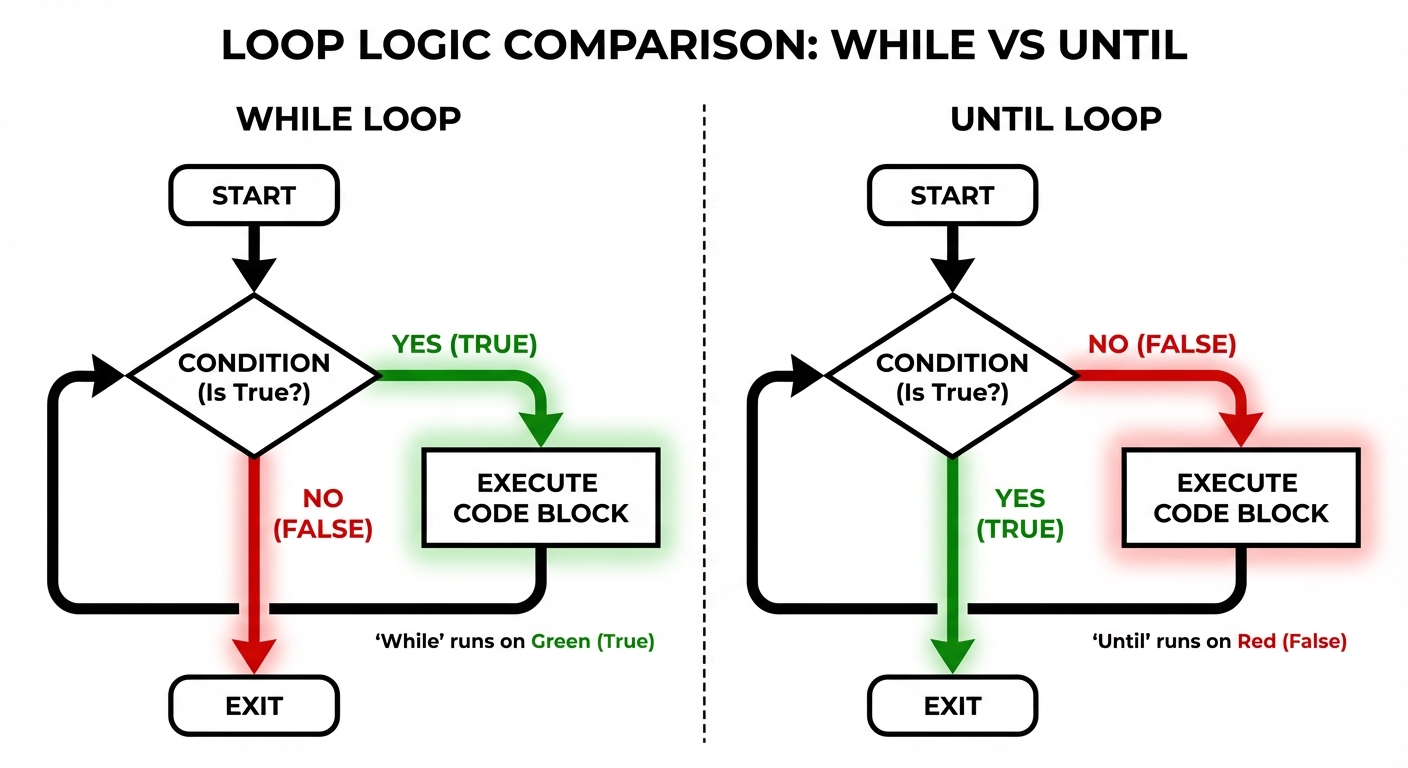

6.2 while Loop

Executes as long as the condition is TRUE.

count=1

while [ $count -le 5 ]

do

echo $count

((count++))

done

6.3 until Loop

Executes as long as the condition is FALSE (runs until the condition becomes true).

count=1

until [ $count -gt 5 ]

do

echo $count

((count++))

done

7. Indexed and Associative Arrays

7.1 Indexed Arrays (Integer Key)

Arrays are zero-indexed variables that can hold multiple values.

- Declaration:

declare -a myArr(Optional) - Initialization:

myArr=(Value1 Value2 Value3) - Access Single Element:

${myArr[0]} - Access All Elements:

{myArr[*]} - Array Length:

${#myArr[@]}

7.2 Associative Arrays (String Key / Dictionary)

Available in Bash 4.0+. Keys are strings instead of integers.

- Declaration:

declare -A userMap(Mandatory) - Assignment:

userMap=([name]="Admin" [id]="001") - Access:

echo ${userMap[name]}

Example:

declare -A cities

cities[UK]="London"

cities[USA]="New York"

echo "City in UK is ${cities[UK]}"

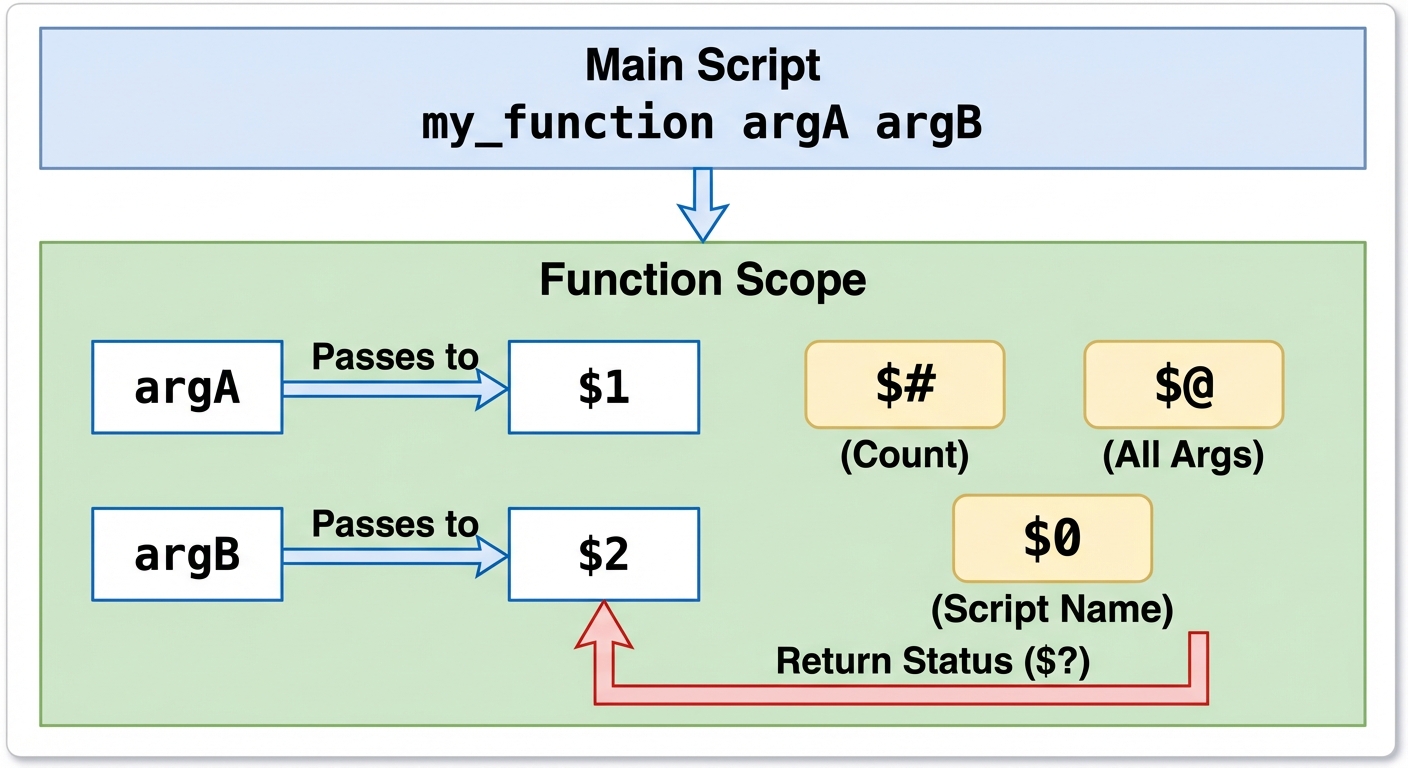

8. User-Defined Functions and Parameter Passing

Functions allow code modularity and reuse.

8.1 Definition Syntax

function_name() {

# commands

}

# OR

function function_name {

# commands

}

8.2 Calling Functions and Passing Parameters

Functions are called by name without parentheses. Parameters are passed as space-separated values.

Inside the function, parameters are accessed using standard positional variables:

$1: First argument$2: Second argument$@: All arguments$#: Number of arguments

Example:

greet_user() {

echo "Hello, $1!"

return 10

}

# Calling the function

greet_user "Alice"

# Checking return value (exit status)

echo "Function returned: $?"

8.3 Variable Scope

- Global: By default, variables defined inside functions are global.

- Local: Use the

localkeyword to restrict scope.

my_func() {

local temp="I am local"

global_var="I am global"

}