Unit 2 - Notes

CSE316

Unit 2: CPU Scheduling

1. Introduction to CPU Scheduling

CPU scheduling is the basis of multiprogrammed operating systems. By switching the CPU among processes, the OS can make the computer more productive.

Basic Concepts

- CPU–I/O Burst Cycle: Process execution consists of a cycle of CPU execution and I/O wait. Processes alternate between these two states.

- CPU Burst: The process is actively executing instructions.

- I/O Burst: The process is waiting for data transfer (disk, network, user input).

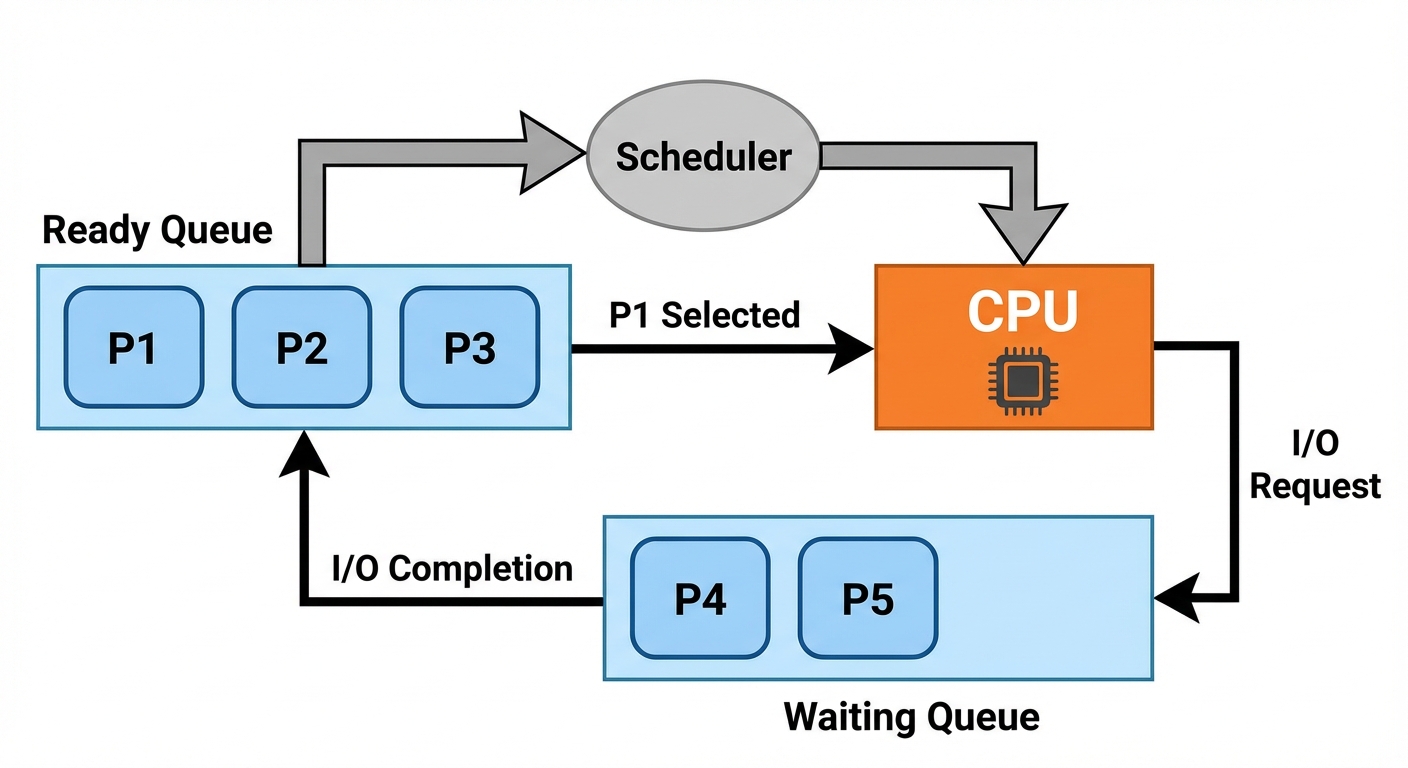

- CPU Scheduler (Short-term Scheduler): Selects from among the processes in memory that are ready to execute and allocates the CPU to one of them.

2. Dispatcher

The dispatcher is the module that gives control of the CPU to the process selected by the short-term scheduler.

Functions of the Dispatcher:

- Context Switching: Saving the state of the old process and loading the state of the new process.

- Switching to User Mode: Changing the execution mode from kernel to user.

- Jumping: Moving to the proper location in the user program to restart that program.

- Dispatch Latency: The time it takes for the dispatcher to stop one process and start another running. This must be minimized.

3. Types of Scheduling

Scheduling decisions may take place when a process:

- Switches from Running to Waiting state (e.g., I/O request).

- Switches from Running to Ready state (e.g., interrupt occurs).

- Switches from Waiting to Ready (e.g., I/O completion).

- Terminates.

Non-Preemptive Scheduling

- Occurs only under conditions 1 and 4.

- Once the CPU has been allocated to a process, the process keeps the CPU until it releases it either by terminating or switching to the waiting state.

- Pros: Simple, low overhead.

- Cons: Poor response time, bugs can hang the system.

Preemptive Scheduling

- Occurs under conditions 2 and 3 (as well as 1 and 4).

- The OS can interrupt a currently running process and move it to the Ready queue to run a higher-priority process.

- Pros: Better responsiveness, necessary for real-time systems.

- Cons: Requires complex race condition handling (shared data).

4. Scheduling Criteria

To compare CPU scheduling algorithms, the following metrics are used:

- CPU Utilization: Keeping the CPU as busy as possible (0% to 100%).

- Throughput: The number of processes that complete their execution per time unit.

- Turnaround Time: The interval from the time of submission of a process to the time of completion.

- Formula:

- Waiting Time: The sum of the periods spent waiting in the ready queue.

- Formula:

- Response Time: The time from the submission of a request until the first response is produced (critical for interactive systems).

5. Scheduling Algorithms

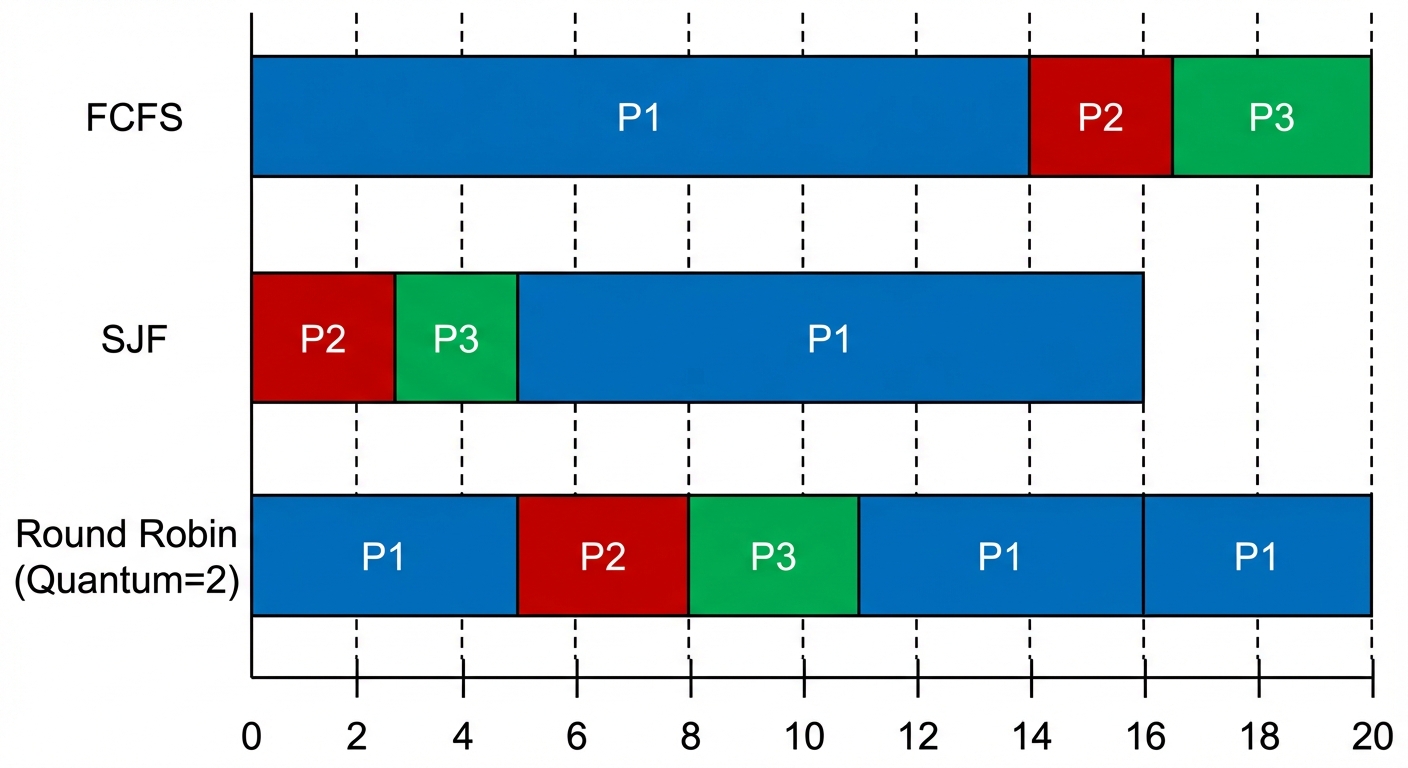

A. First-Come, First-Served (FCFS)

- Type: Non-preemptive.

- Mechanism: The process that requests the CPU first is allocated the CPU first using a FIFO queue.

- Characteristics:

- Simple to implement.

- Convoy Effect: Short processes wait behind a long process (like a CPU-bound process blocking I/O-bound processes), leading to low CPU and I/O utilization.

- High average waiting time.

B. Shortest Job First (SJF)

- Type: Can be Non-preemptive or Preemptive (Shortest Remaining Time First - SRTF).

- Mechanism: Associates with each process the length of its next CPU burst. The CPU is assigned to the process with the smallest next burst.

- Characteristics:

- Optimal Algorithm: Gives the minimum average waiting time for a given set of processes.

- Difficulty: Cannot know the length of the next CPU burst in advance (must predict using exponential averaging).

C. Priority Scheduling

- Mechanism: A priority number (integer) is associated with each process. The CPU is allocated to the process with the highest priority.

- Issue - Starvation (Indefinite Blocking): Low priority processes may never execute.

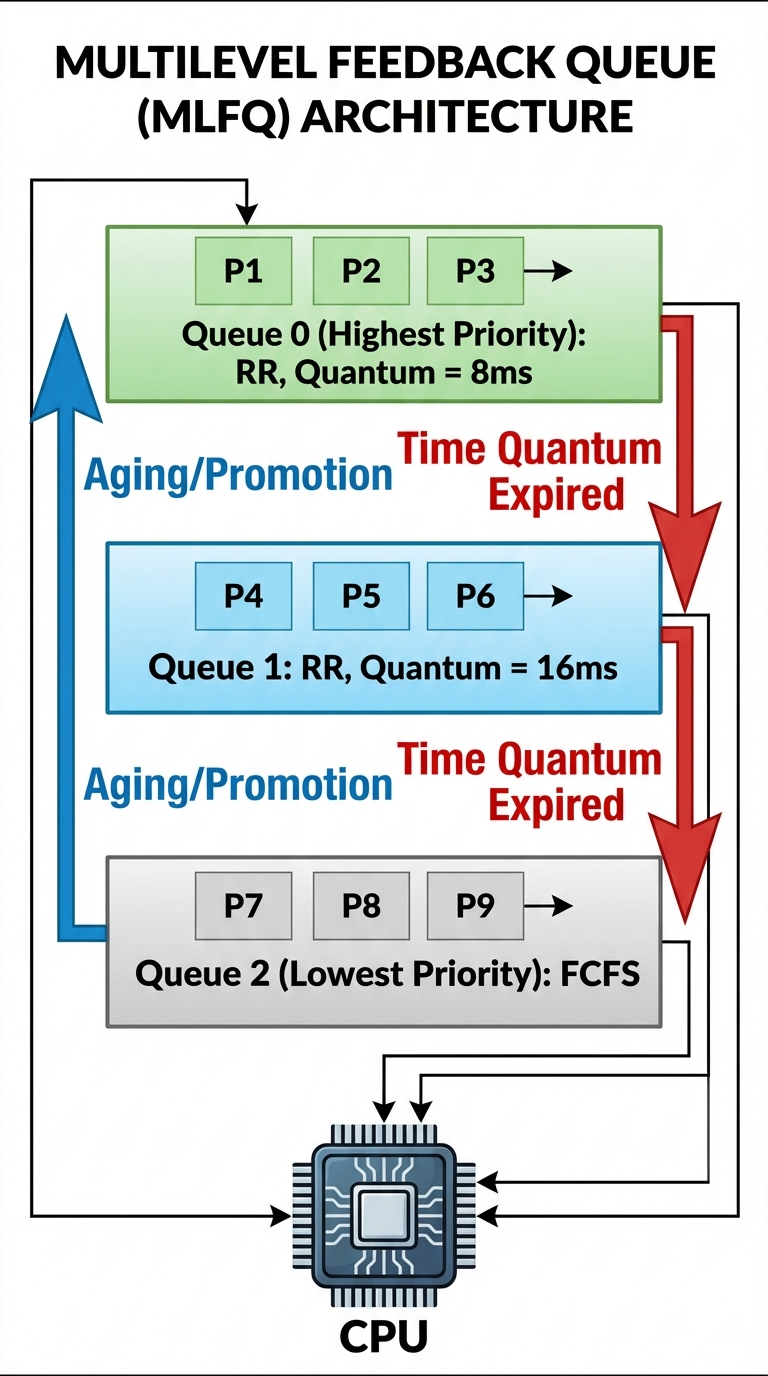

- Solution - Aging: Gradually increase the priority of processes that wait in the system for a long time.

D. Round Robin (RR)

- Type: Preemptive.

- Mechanism: Designed for time-sharing systems. A small unit of time called a Time Quantum (or Time Slice) is defined (e.g., 10-100 ms).

- The ready queue is treated as a circular queue.

- The CPU scheduler goes around the ready queue, allocating the CPU to each process for a time interval of up to 1 time quantum.

- Performance:

- Depends heavily on the size of the time quantum ().

- If is extremely large FCFS.

- If is extremely small High context switch overhead.

E. Multilevel Queue Scheduling

- Partitions the ready queue into several separate queues (e.g., foreground/interactive and background/batch).

- Processes are permanently assigned to one queue based on memory size, process priority, or process type.

- Each queue has its own scheduling algorithm (e.g., RR for foreground, FCFS for background).

F. Multilevel Feedback Queue (MLFQ)

- Allows a process to move between queues.

- Philosophy: Separate processes according to the characteristics of their CPU bursts. If a process uses too much CPU time, it is moved to a lower-priority queue. This leaves I/O-bound and interactive processes in the higher-priority queues.

- Parameters:

- Number of queues.

- Scheduling algorithm for each queue.

- Method used to determine when to upgrade a process.

- Method used to determine when to demote a process.

6. Thread Scheduling

Modern operating systems schedule kernel threads, not processes. User-level threads must be mapped to kernel-level threads.

- Process-Contention Scope (PCS): Used in Many-to-One and Many-to-Many models. The thread library schedules user-level threads to run on an available LWP (Light Weight Process). This happens purely in user space.

- System-Contention Scope (SCS): Used in One-to-One models (Windows, Linux). The kernel decides which kernel-level thread to schedule onto a CPU.

7. Multiprocessor Scheduling

When multiple CPUs are available, load sharing becomes possible, but scheduling becomes more complex.

Architecture Approaches

- Asymmetric Multiprocessing: Only one processor (the master) accesses the system data structures, reducing the need for data sharing. Other processors run user code.

- Symmetric Multiprocessing (SMP): Each processor is self-scheduling. All processes may be in a common ready queue, or each processor may have its own private queue. Most modern OSs (Windows, Linux, macOS) use SMP.

Key Concepts in SMP

- Processor Affinity: A process has an affinity for the processor on which it is currently running (due to cache memory contents).

- Soft Affinity: OS attempts to keep process on same CPU but doesn't guarantee it.

- Hard Affinity: System calls allow specifying a subset of processors where a process can run.

- Load Balancing: Keeps the workload evenly distributed.

- Push Migration: A specific task checks load and pushes processes from overloaded to idle CPUs.

- Pull Migration: Idle processors pull a waiting task from a busy processor.

8. Real-Time Scheduling

Real-time systems are defined by their ability to complete a specific task within a specific time constraint.

Types

- Soft Real-Time: Critical real-time processes get preference over non-critical processes, but no guarantee as to when it will be scheduled.

- Hard Real-Time: Tasks must be serviced by their deadline; service after the deadline is the same as no service at all.

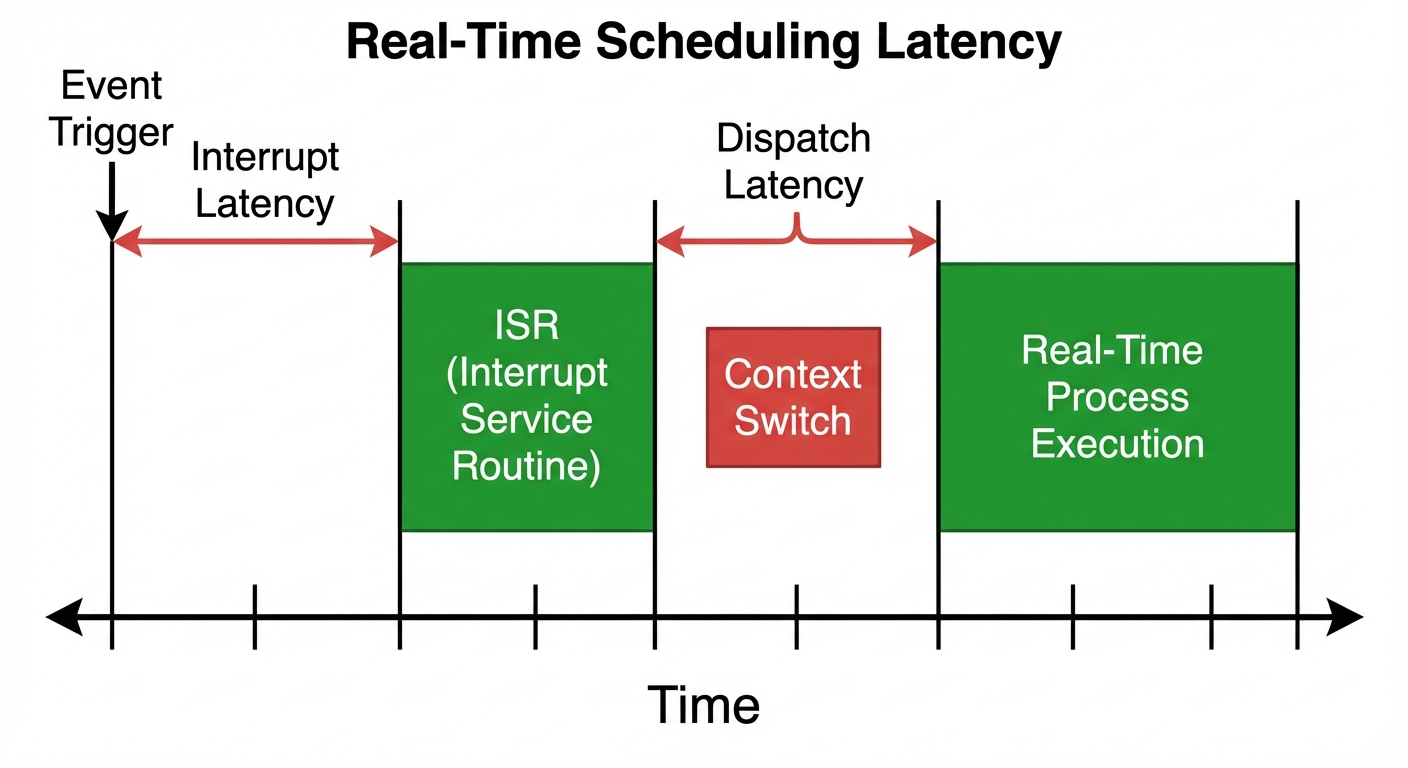

Latency Issues

To ensure real-time performance, the OS must minimize:

- Interrupt Latency: Time from the arrival of an interrupt to the start of the interrupt service routine (ISR).

- Dispatch Latency: Time for the scheduler to take the current process off the CPU and switch to another.

Real-Time Algorithms

- Rate Monotonic Scheduling: A static priority policy using preemption. Priorities are assigned based on the cycle period (shorter period = higher priority).

- Earliest Deadline First (EDF): Dynamic priority assignment. The closer the deadline, the higher the priority.