Unit 5 - Notes

CSE325

Unit 5: Multithreading & Synchronization

1. POSIX Thread Creation and Termination

1.1 Introduction to Threads

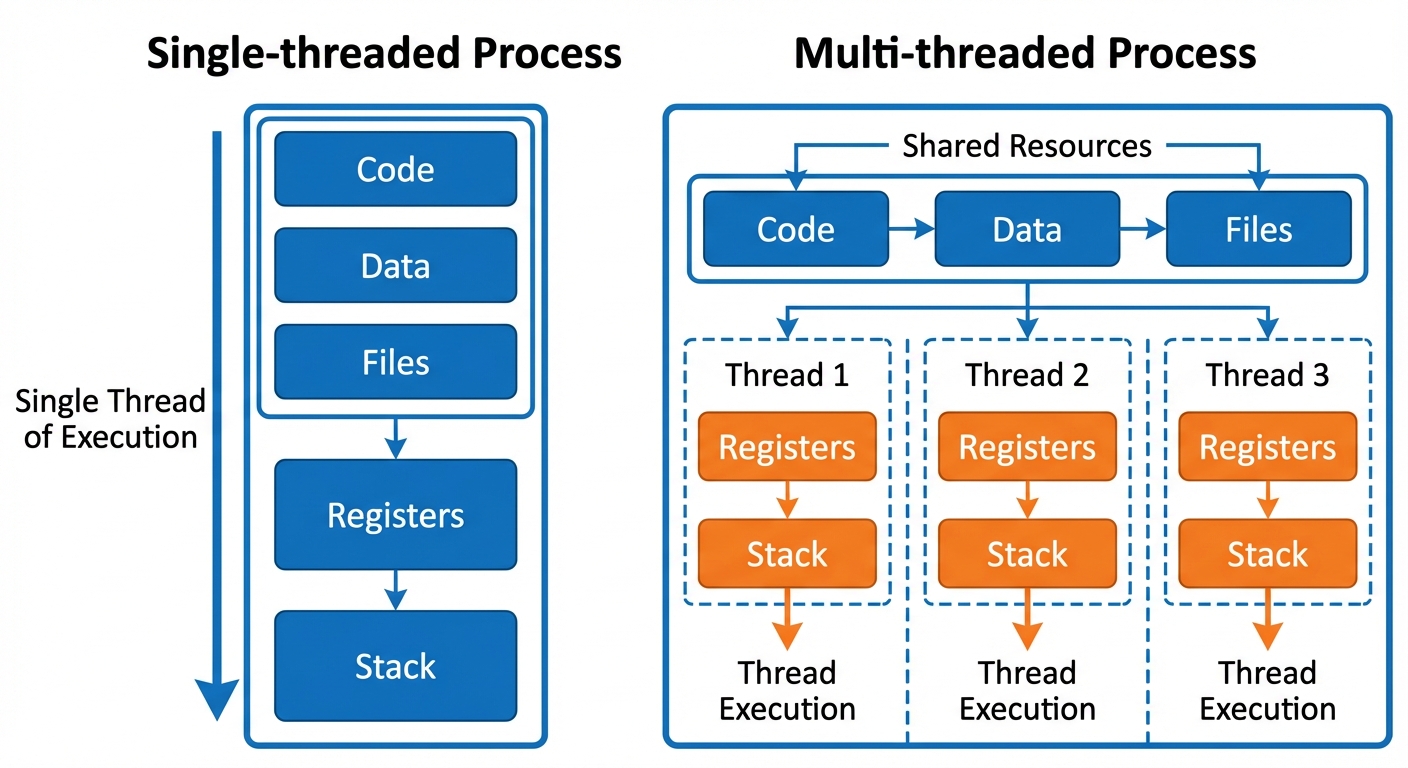

A thread is a basic unit of CPU utilization, consisting of a thread ID, a program counter, a register set, and a stack. It shares with other threads belonging to the same process its code section, data section, and other operating-system resources, such as open files and signals.

- Process (Heavyweight): Has a single thread of control.

- Thread (Lightweight): Multiple threads of control within the same address space.

1.2 The Pthreads API

POSIX Threads (Pthreads) is a standard for threading defined by IEEE POSIX 1003.1c. In Linux, programs using pthreads must be compiled with the -pthread (or -lpthread) flag.

Key Functions

-

pthread_create: Spawns a new thread.

Cint pthread_create(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*start_routine) (void *), void *arg);thread: Pointer to a buffer where the unique thread ID is stored.attr: Attributes for the thread (NULL for default).start_routine: Pointer to the function the thread will execute.arg: Single argument passed to the function.

-

pthread_exit: Terminates the calling thread.

Cvoid pthread_exit(void *retval);retval: Return value passed to the thread joining this one.

-

pthread_join: Waits for a specific thread to terminate (similar towait()for processes).

Cint pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **retval); -

pthread_self: Returns the ID of the calling thread.

Cpthread_t pthread_self(void);

1.3 Lab Example: Basic Thread Creation

File: thread_creation.c

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

// Thread function

void* print_message(void* ptr) {

char* message = (char*)ptr;

printf("%s \n", message);

pthread_exit(NULL); // Terminate thread

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread1, thread2;

const char* msg1 = "Thread 1: Hello World";

const char* msg2 = "Thread 2: OS Laboratory";

int ret1, ret2;

// Create threads

ret1 = pthread_create(&thread1, NULL, print_message, (void*)msg1);

if(ret1) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error - pthread_create() return code: %d\n", ret1);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

ret2 = pthread_create(&thread2, NULL, print_message, (void*)msg2);

if(ret2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error - pthread_create() return code: %d\n", ret2);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Wait for threads to finish

pthread_join(thread1, NULL);

pthread_join(thread2, NULL);

printf("Main thread: Both threads completed.\n");

return 0;

}

Compilation and Execution:

gcc thread_creation.c -o thread_creation -pthread

./thread_creation

2. Race Conditions and Critical Sections

2.1 The Critical Section Problem

When multiple threads access and manipulate the same data concurrently, the outcome of the execution depends on the particular order in which the access takes place. This is called a Race Condition.

- Critical Section (CS): A segment of code where a thread accesses shared resources (global variables, common files, etc.).

- Criteria for Solution:

- Mutual Exclusion: If thread T1 is in its CS, no other thread can be in its CS.

- Progress: If no thread is in the CS, the decision of who enters next cannot be postponed indefinitely.

- Bounded Waiting: There must be a limit on the number of times other threads are allowed to enter their CS after a thread has made a request to enter its CS.

2.2 Visualizing the Race Condition

Consider two threads trying to increment a global variable counter = 5.

- Thread A reads

counter(5). - Context switch occurs. Thread B reads

counter(5). - Thread B increments value to 6 and writes to memory.

- Context switch back to A. Thread A (holding old value 5) increments to 6 and writes to memory.

- Result:

counteris 6, but it should be 7. This is the "Lost Update" problem.

[Image generation failed: A chronological timeline diagram illustrating a Ra...]

2.3 Lab Example: Simulating a Race Condition

File: race_condition.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int counter = 0; // Shared resource

void* increment(void* arg) {

unsigned long i = 0;

// Massive loop to increase probability of context switch during execution

for (i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

counter += 1; // Critical Section (Read, Modify, Write)

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t t1, t2;

pthread_create(&t1, NULL, increment, NULL);

pthread_create(&t2, NULL, increment, NULL);

pthread_join(t1, NULL);

pthread_join(t2, NULL);

printf("Final Counter Value: %d (Expected: 2000000)\n", counter);

return 0;

}

Note: Run this multiple times. You will likely see results less than 2,000,000 due to race conditions.

3. Mutex Locks (Mutual Exclusion)

3.1 Concept

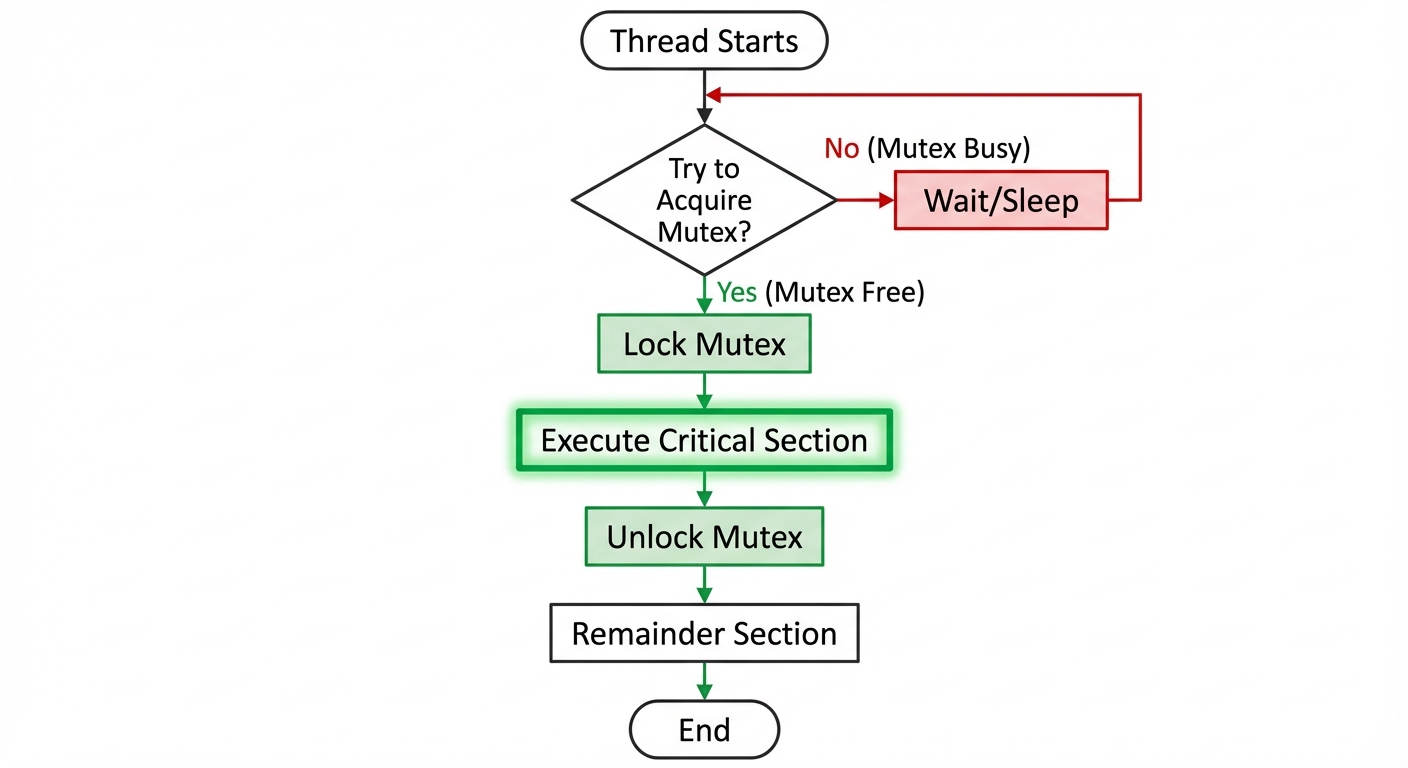

A Mutex is a synchronization primitive that grants exclusive access to the shared resource to only one thread. It acts like a lock on a door.

- If the lock is set, other threads attempting to lock it are blocked (put to sleep) until the thread holding the lock releases it.

3.2 Mutex API

- Initialization:

pthread_mutex_init(&mutex, NULL); - Locking:

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);(Entry Section) - Unlocking:

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);(Exit Section) - Destruction:

pthread_mutex_destroy(&mutex);

3.3 Lab Example: Solving Race Condition with Mutex

File: mutex_solution.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

int counter = 0;

pthread_mutex_t lock; // Declare mutex

void* increment(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

// Entry Section

pthread_mutex_lock(&lock);

// Critical Section

counter += 1;

// Exit Section

pthread_mutex_unlock(&lock);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t t1, t2;

// Initialize Mutex

if (pthread_mutex_init(&lock, NULL) != 0) {

printf("\n Mutex init has failed\n");

return 1;

}

pthread_create(&t1, NULL, increment, NULL);

pthread_create(&t2, NULL, increment, NULL);

pthread_join(t1, NULL);

pthread_join(t2, NULL);

// Destroy Mutex

pthread_mutex_destroy(&lock);

printf("Final Counter Value: %d (Expected: 2000000)\n", counter);

return 0;

}

4. Semaphores

4.1 Concept

A semaphore is a more robust synchronization tool than a mutex. It is an integer variable S that, apart from initialization, is accessed only through two standard atomic operations: wait() and signal().

- P (Proberen/Wait/Down): Decrements the value. If

S <= 0, the process blocks. - V (Verhogen/Signal/Post/Up): Increments the value. Wakes up a blocked process if any.

Types:

- Binary Semaphore: Value ranges between 0 and 1 (Similar to Mutex).

- Counting Semaphore: Value can range over an unrestricted domain (Used to control access to a resource with finite instances).

4.2 Semaphore API (POSIX)

Header: <semaphore.h>

sem_init(sem_t *sem, int pshared, unsigned int value): Initialize semaphore.pshared=0for threads.sem_wait(sem_t *sem): Decrements (locks). Blocks if value is 0.sem_post(sem_t *sem): Increments (unlocks).sem_destroy(sem_t *sem): Cleans up.

4.3 Lab Example: Binary Semaphore (Synchronization)

File: semaphore_demo.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <semaphore.h>

#include <unistd.h>

sem_t mutex; // Define semaphore

void* thread_func(void* arg) {

// Wait (P operation)

sem_wait(&mutex);

// Critical Section

printf("\nThread %ld entered Critical Section..\n", (long)pthread_self());

// Simulate work

sleep(1);

printf("Thread %ld exiting Critical Section..\n", (long)pthread_self());

// Signal (V operation)

sem_post(&mutex);

return NULL;

}

int main() {

// Initialize semaphore to 1 (Binary Semaphore behavior)

sem_init(&mutex, 0, 1);

pthread_t t1, t2;

pthread_create(&t1, NULL, thread_func, NULL);

sleep(2); // Ensure t1 starts first to demonstrate locking

pthread_create(&t2, NULL, thread_func, NULL);

pthread_join(t1, NULL);

pthread_join(t2, NULL);

sem_destroy(&mutex);

return 0;

}

4.4 Difference between Mutex and Semaphore

| Feature | Mutex | Binary Semaphore |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | Locked by a thread, must be unlocked by the same thread. | Can be waited on by one thread and posted by another. |

| Nature | Locking mechanism. | Signaling mechanism. |

| Speed | Generally faster. | Slightly slower due to kernel involvement. |