Unit 6 - Notes

CSE325

Unit 6: Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

1. Introduction to IPC

Inter-Process Communication (IPC) refers to the mechanisms provided by an operating system that allow processes to manage shared data. Typically, applications can be either independent or cooperating.

- Independent Processes: Execution is not affected by other processes.

- Cooperating Processes: Can affect or be affected by other executing processes. These processes require IPC mechanisms to exchange data and control signals.

Why IPC is needed:

- Information Sharing: Multiple users needing access to the same file.

- Computation Speedup: Breaking a task into sub-tasks to run in parallel.

- Modularity: Constructing a system in modular fashion (e.g., microkernel architecture).

There are two fundamental models of IPC:

- Shared Memory: A region of memory that is shared by cooperating processes.

- Message Passing: Communication takes place by means of messages exchanged between cooperating processes (e.g., Pipes, Sockets).

2. Anonymous Pipes

Concept

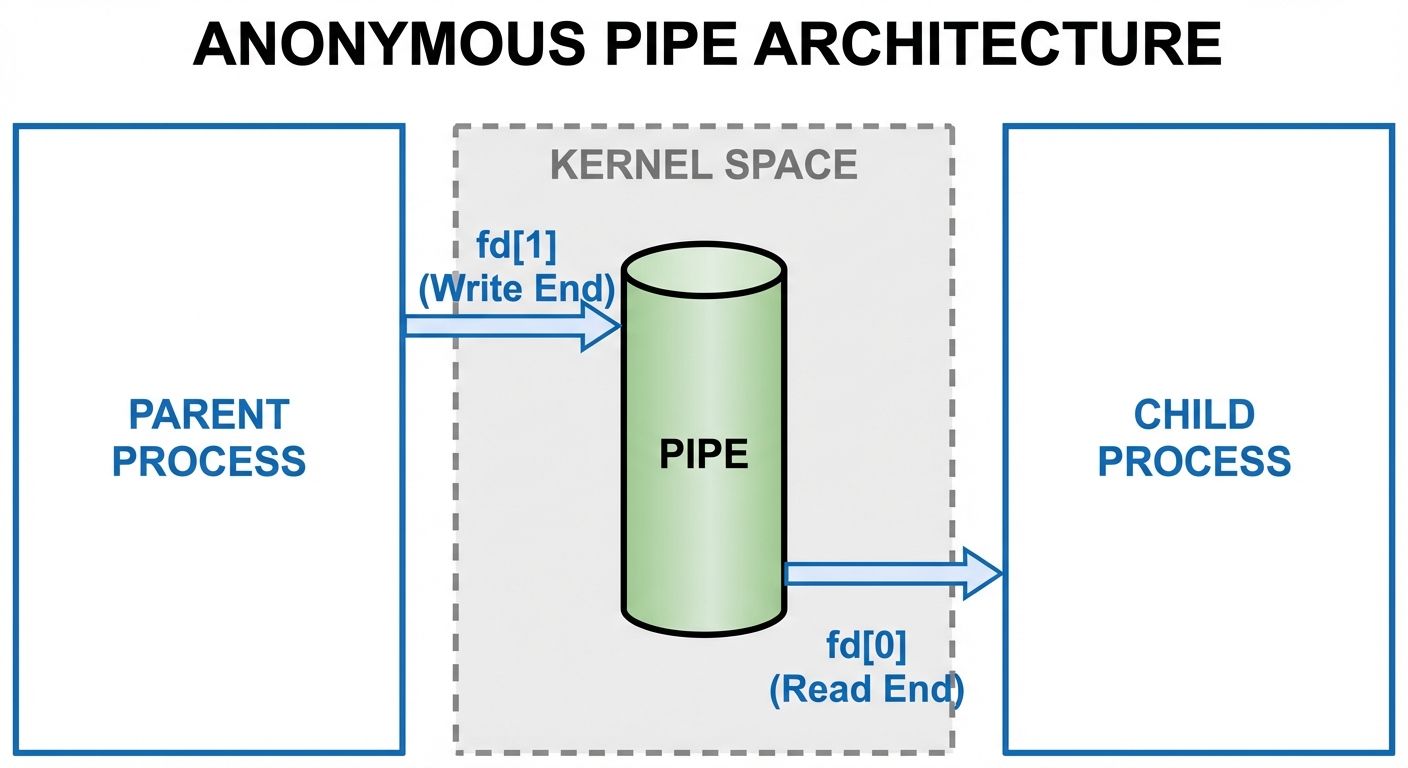

A Pipe is one of the earliest and simplest IPC mechanisms in Unix/Linux. It essentially creates a unidirectional data channel that can be used for inter-process communication.

- Unidirectional: Data flows in one direction only (Half-duplex). If two-way communication is needed, two pipes must be established.

- Ancestry Requirement: Anonymous pipes can only be used between processes that have a common ancestor (e.g., Parent and Child).

- FIFO Nature: Data written to the pipe is read in a First-In-First-Out manner.

- Kernel Buffer: The pipe is essentially a buffer in kernel memory.

System Calls and Implementation

The pipe() system call creates the buffer.

#include <unistd.h>

int pipe(int fd[2]);

- Parameters: An integer array of size 2.

fd[0]: Refers to the read end of the pipe.fd[1]: Refers to the write end of the pipe.

- Return Value: Returns 0 on success, -1 on failure.

Implementation Logic (Parent-Child)

- Parent calls

pipe(fd). - Parent calls

fork(). Now both parent and child have copies of the file descriptors. - Parent (Writer): Closes

fd[0](read end), writes tofd[1]. - Child (Reader): Closes

fd[1](write end), reads fromfd[0].

C Code Example: Anonymous Pipe

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

int fd[2];

pid_t p;

char buffer[100];

// Create pipe

if (pipe(fd) < 0) {

perror("Pipe Failed");

return 1;

}

p = fork();

if (p < 0) {

perror("Fork Failed");

return 1;

}

else if (p > 0) {

// PARENT PROCESS (Writer)

char msg[] = "Hello from Parent!";

close(fd[0]); // Close unused read end

write(fd[1], msg, strlen(msg) + 1);

printf("Parent: Wrote message to pipe.\n");

close(fd[1]); // Close write end after finishing

}

else {

// CHILD PROCESS (Reader)

close(fd[1]); // Close unused write end

read(fd[0], buffer, 100);

printf("Child: Read message -> %s\n", buffer);

close(fd[0]); // Close read end

}

return 0;

}

3. Named Pipes (FIFOs)

Concept

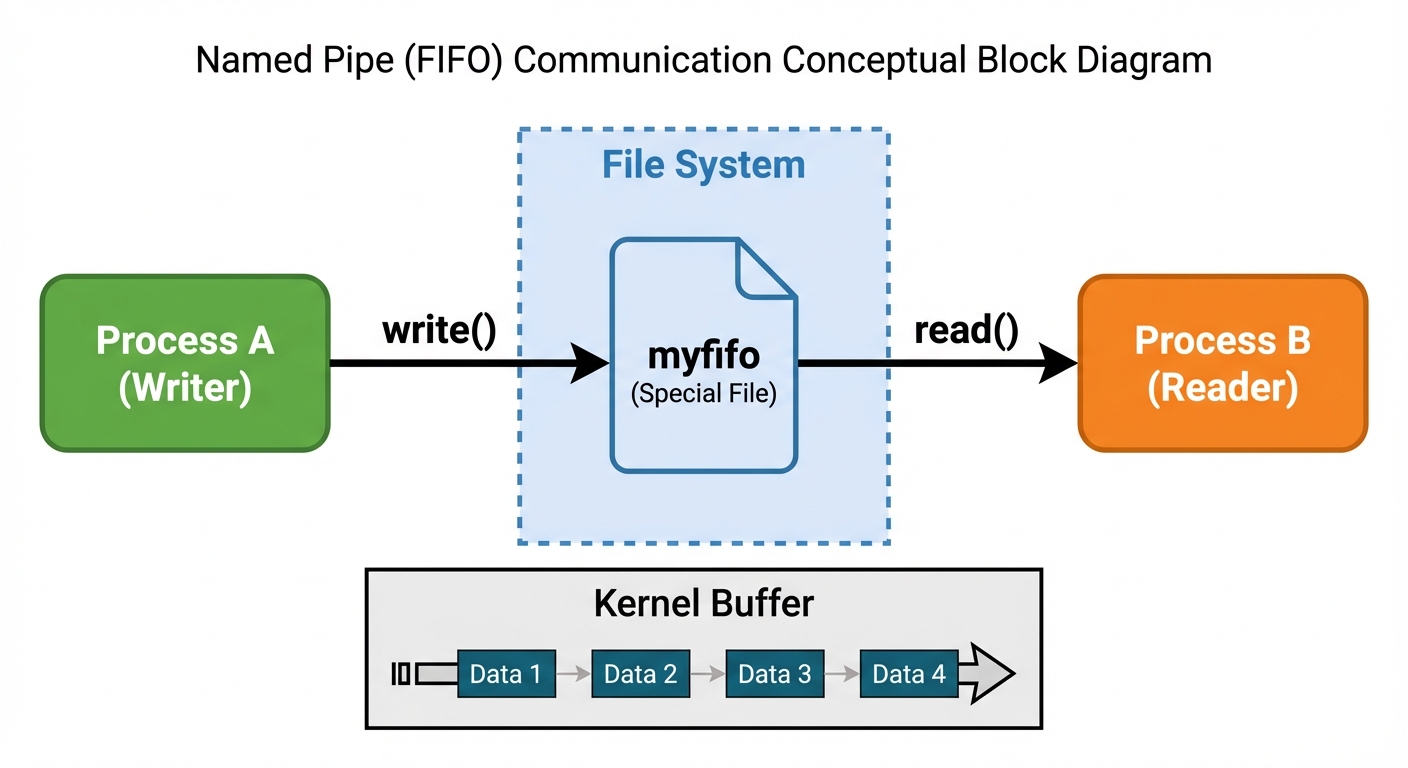

Standard pipes (anonymous) have a major limitation: they disappear when the processes terminate and only work between related processes. Named Pipes (FIFOs) solve this.

- Persistence: A Named Pipe exists as a special file in the file system. It persists even after all processes using it have terminated.

- Unrelated Processes: Any process can communicate with any other process, provided they have the necessary file permissions to access the FIFO.

- Bidirectional capability: While a single FIFO is unidirectional strictly speaking, multiple processes can open it for read/write (though typically two FIFOs are used for full-duplex reliability).

System Calls

- Creation:

C#include <sys/types.h> #include <sys/stat.h> int mkfifo(const char *pathname, mode_t mode); - Access: Once created, FIFOs are accessed using standard

open(),read(),write(), andclose()system calls.

C Code Example: Named FIFOs

This requires two separate programs running simultaneously.

Program 1: The Writer

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

int fd;

char * myfifo = "/tmp/myfifo";

// Create the FIFO (named pipe)

mkfifo(myfifo, 0666);

printf("Writer: Opening FIFO...\n");

// Open FIFO for Write only

fd = open(myfifo, O_WRONLY);

char str[80];

printf("Writer: Enter message: ");

fgets(str, 80, stdin);

write(fd, str, strlen(str)+1);

close(fd);

// Ideally, unlink(myfifo) should be called by one process to cleanup

return 0;

}

Program 2: The Reader

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

int fd;

char * myfifo = "/tmp/myfifo";

char str[80];

printf("Reader: Opening FIFO...\n");

// Open FIFO for Read only

fd = open(myfifo, O_RDONLY);

read(fd, str, 80);

printf("Reader: Received: %s\n", str);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

4. Shared Memory

Concept

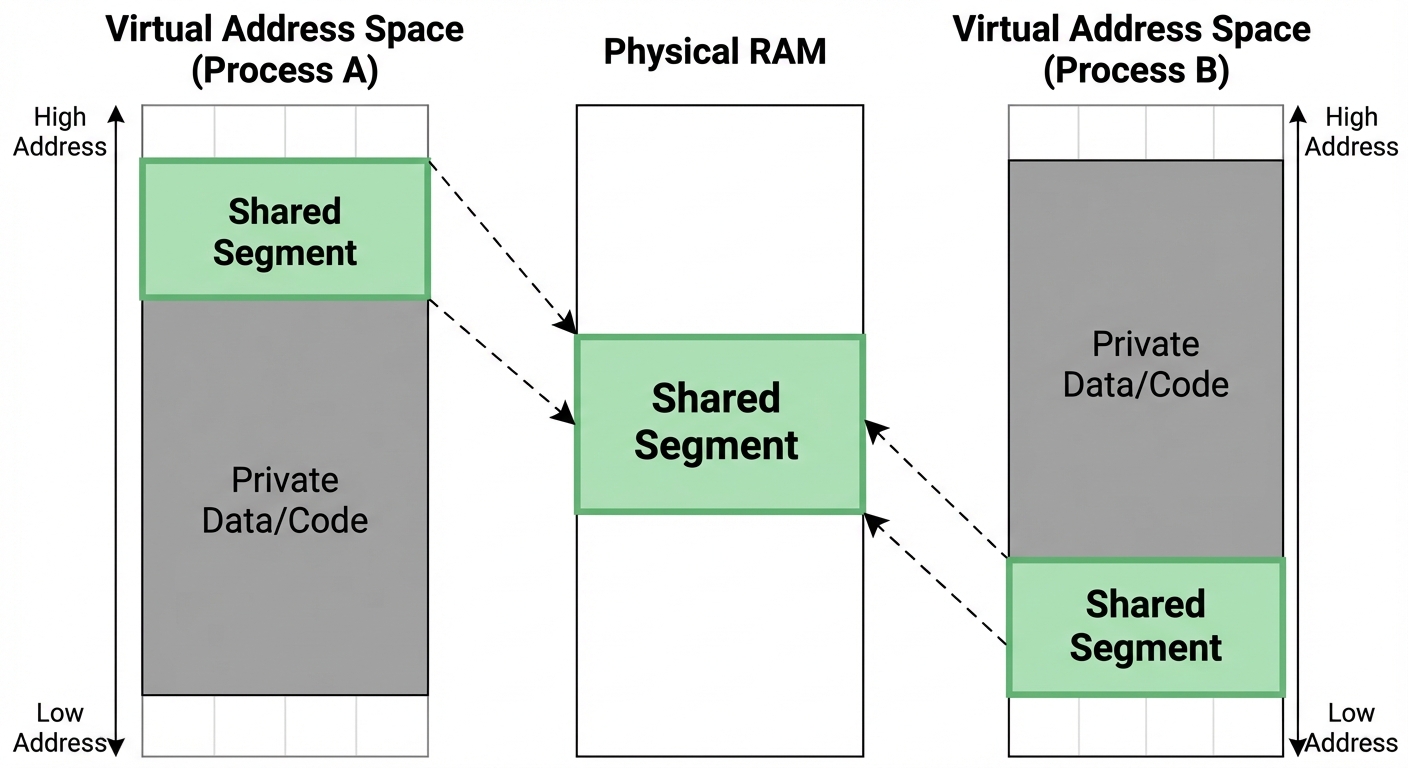

Shared Memory is the fastest IPC mechanism. Instead of the OS copying data from one process's memory to the kernel and then to another process (like pipes), the OS maps a memory segment into the address space of multiple processes.

- Mechanism: Two or more processes agree on a segment of physical memory. They map this segment into their own virtual address spaces.

- Speed: Very fast because no system calls are required to access data once the memory is mapped; it is treated as standard memory access.

- Synchronization: The OS does not provide automatic synchronization. Processes must use semaphores or mutexes to prevent race conditions (e.g., Process A writing while Process B is reading).

System V Shared Memory API

We typically use the System V API in Linux Lab environments.

ftok(): Generates a unique key based on a file path and project ID.shmget(): Creates a shared memory segment or gets the ID of an existing one.int shmget(key_t key, size_t size, int shmflg);

shmat(): Attaches the shared memory segment to the address space of the calling process.void *shmat(int shmid, const void *shmaddr, int shmflg);

shmdt(): Detaches the shared memory segment from the process.shmctl(): Control operations (like deleting the segment usingIPC_RMID).

C Code Example: Shared Memory

We will use a Writer process to write to memory and a Reader process to read from it.

Program 1: Writer (shm_write.c)

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/shm.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// ftok to generate unique key

key_t key = ftok("shmfile", 65);

// shmget returns an identifier in shmid

// 1024 is size, 0666 is permission

int shmid = shmget(key, 1024, 0666|IPC_CREAT);

// shmat to attach to shared memory

char *str = (char*) shmat(shmid, (void*)0, 0);

printf("Write Data : ");

gets(str); // Unsafe in production, used here for lab simplicity

printf("Data written in memory: %s\n", str);

// detach from shared memory

shmdt(str);

return 0;

}

Program 2: Reader (shm_read.c)

#include <sys/ipc.h>

#include <sys/shm.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// ftok to generate unique key (must be same file/id as writer)

key_t key = ftok("shmfile", 65);

// shmget returns an identifier

int shmid = shmget(key, 1024, 0666|IPC_CREAT);

// shmat to attach to shared memory

char *str = (char*) shmat(shmid, (void*)0, 0);

printf("Data read from memory: %s\n", str);

// detach from shared memory

shmdt(str);

// destroy the shared memory

shmctl(shmid, IPC_RMID, NULL);

return 0;

}

Comparison Table: Pipes vs Shared Memory

| Feature | Pipes / FIFOs | Shared Memory |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Slower (requires data copying: User Kernel User) | Faster (Zero-copy, direct RAM access) |

| Communication | Stream of bytes | Direct memory addressing |

| Synchronization | Implicit (OS handles blocking on read/write) | Explicit (User must implement Semaphores/Mutex) |

| Usage | Simple data transfer | Large or complex data structures |