Unit 5 - Notes

CSE316

Unit 5: Memory Management

1. Logical & Physical Address Space

To manage memory efficiently, the operating system distinguishes between the address view of the process and the actual storage location in hardware.

- Logical Address (Virtual Address):

- Generated by the CPU during program execution.

- It is the address seen by the user program.

- The set of all logical addresses generated by a program is the Logical Address Space.

- Physical Address:

- The actual address in the memory unit (RAM) where data is stored.

- The set of all physical addresses corresponding to logical addresses is the Physical Address Space.

- The user program deals with logical addresses; it never sees the real physical addresses.

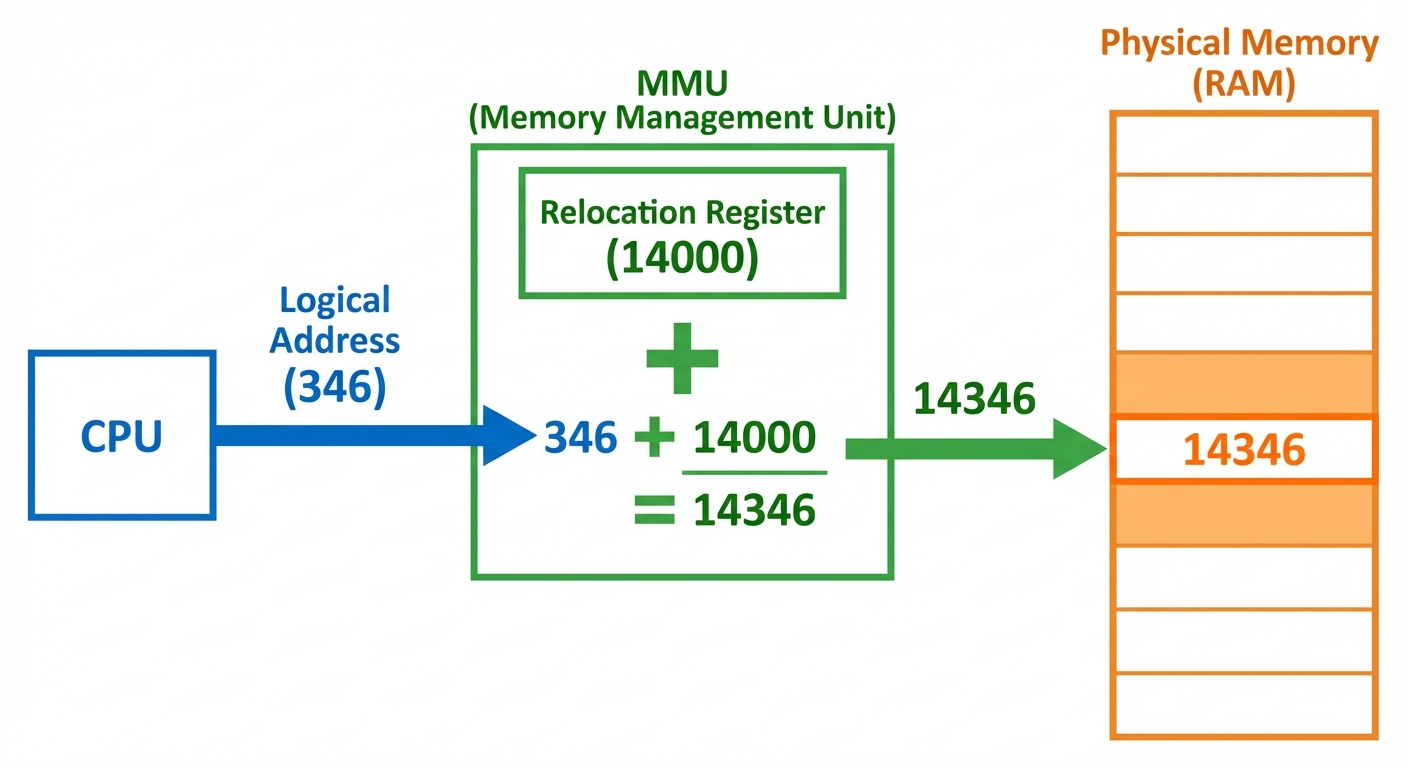

Memory Management Unit (MMU)

The MMU is a hardware device that maps logical addresses to physical addresses at runtime.

- Relocation Register: The base register value is added to every address generated by a user process at the time it is sent to memory.

- Formula:

Physical Address = Logical Address + Relocation Register Value

2. Basic Memory Management Schemes

Swapping

Swapping allows a process to be temporarily moved out of main memory to a backing store (disk) and then brought back into memory for continued execution. This allows the total physical address space of all active processes to exceed the real physical memory.

- Roll out, Roll in: Used for priority-based scheduling. Lower priority processes are swapped out so higher priority processes can load and run.

- Backing Store: Fast disk large enough to accommodate copies of all memory images for all users.

Overlays

Overlays are used to enable a process to be larger than the amount of memory allocated to it.

- Concept: Keep in memory only those instructions and data that are needed at any given time. When other instructions are needed, they are loaded into space occupied previously by instructions that are no longer needed.

- Implementation: Implemented by the user (programmer), not the OS. The programmer must define the overlay structure. This is complex and rarely used in modern systems due to virtual memory.

3. Contiguous Memory Allocation

In this scheme, each process is contained in a single contiguous section of memory. Memory is usually divided into two partitions: one for the resident OS and one for user processes.

Fragmentation

Fragmentation occurs when memory is wasted due to allocation methods.

- External Fragmentation:

- Total memory space exists to satisfy a request, but it is not contiguous (scattered holes).

- Solution: Compaction (shuffling memory contents to place all free memory together) or Paging.

- Internal Fragmentation:

- Allocated memory may be slightly larger than requested memory. The size difference is memory internal to a partition, but not being used.

- Common in: Fixed partitioning or paging (last page is rarely full).

Allocation Strategies

When a process needs memory, the OS searches the set of holes (free blocks).

- First Fit: Allocate the first hole that is big enough. (Fastest).

- Best Fit: Allocate the smallest hole that is big enough. (Produces the smallest leftover hole).

- Worst Fit: Allocate the largest hole. (Produces the largest leftover hole).

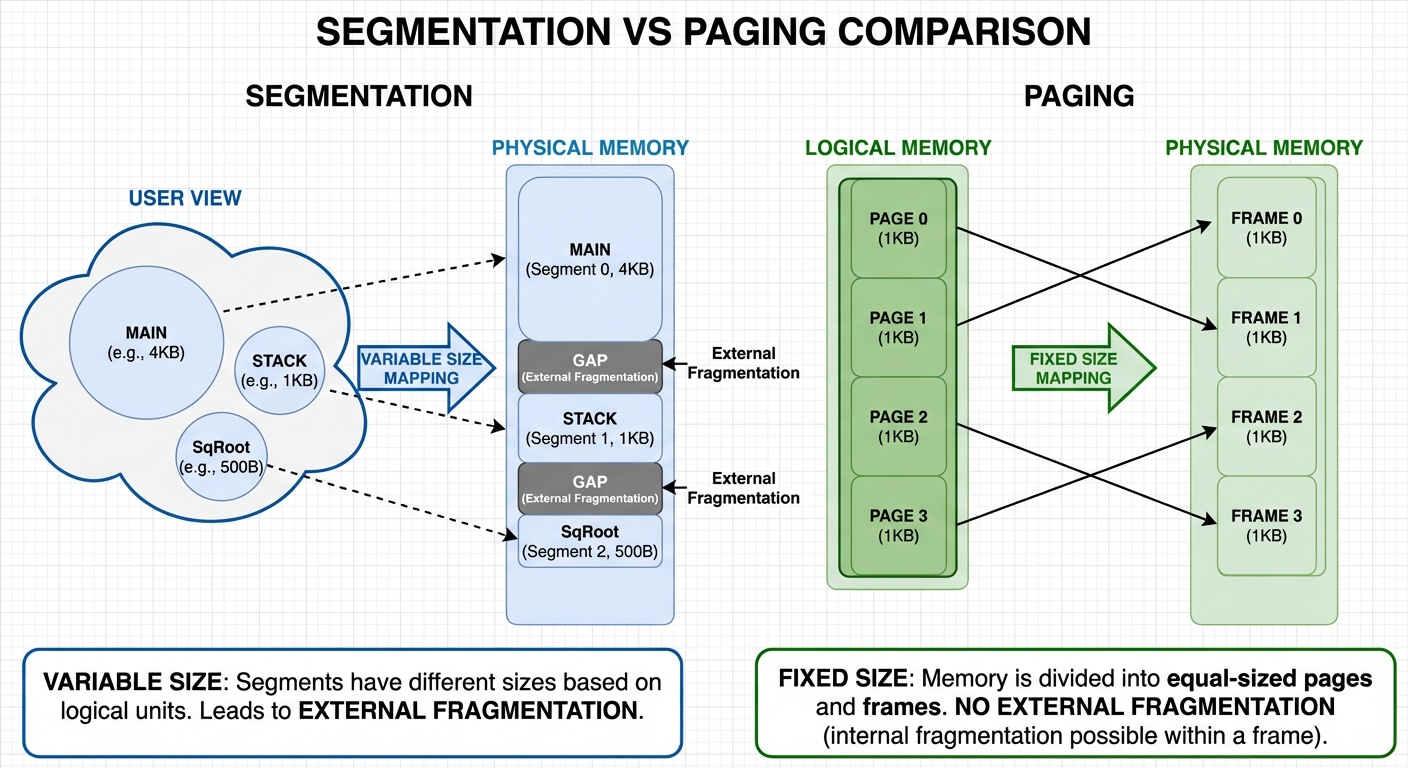

4. Paging

Paging is a memory management scheme that eliminates the need for contiguous allocation of physical memory. It avoids external fragmentation.

Basic Concepts

- Frames: Physical memory is broken into fixed-sized blocks called frames.

- Pages: Logical memory is broken into blocks of the same size called pages.

- Page Table: A data structure used by the OS to map Page Numbers to Frame Numbers.

Address Translation Architecture

Every address generated by the CPU is divided into two parts:

- Page Number (p): Used as an index into a page table.

- Page Offset (d): Combined with the base address of the frame to define the physical memory address.

Physical Address = (Frame Number * Frame Size) + Offset

[Image generation failed: A diagram of Paging Hardware Architecture. On the ...]

Multi-level Paging (Hierarchical Paging)

For very large logical address spaces (e.g., 64-bit systems), the page table itself becomes too large to fit in one contiguous block of memory.

- Concept: Break the page table into smaller pieces. We page the page table.

- Two-Level Paging: The logical address is split into:

Outer Page Table Index | Inner Page Table Index | Offset.

5. Segmentation

Segmentation supports the user view of memory. A user does not view memory as a linear array of bytes, but as a collection of variable-sized segments (e.g., main program, stack, symbol table, distinct functions).

Mechanism

- Logical Address: A tuple

<segment-number, offset>. - Segment Table: Maps two-dimensional user-defined addresses into one-dimensional physical addresses. Each entry has:

- Base: Starting physical address.

- Limit: Length of the segment.

- Protection: Validation checks if

offset < Limit. If not, a trap (segmentation fault) is generated.

Segmentation with Paging

To solve the external fragmentation and long search times inherent in pure segmentation, systems (like Intel x86) use segmentation with paging.

- The CPU generates a logical address (Segment #, Offset).

- The segmentation unit produces a Linear Address.

- The paging unit maps the linear address to a Physical Address.

6. Virtual Memory & Demand Paging

Virtual Memory allows the execution of processes that are not completely in memory. It separates user logical memory from physical memory.

Demand Paging

Pages are loaded into memory only when they are needed (demanded) during program execution. This is a "Lazy Swapper" approach.

Page Fault

A Page Fault occurs when a process tries to access a page that is not currently in main memory (the valid-invalid bit in the page table is set to 'invalid').

Steps in Handling a Page Fault:

- Trap: The OS traps the interrupt caused by the invalid access.

- Check: OS checks if the reference was valid (logical address) but not in memory.

- Find Frame: OS finds a free frame in physical memory.

- Disk Operation: OS issues a disk operation to read the desired page into the newly allocated frame.

- Modify Table: Once the read is complete, the internal table and page table are updated to indicate the page is now in memory (valid bit = 1).

- Restart: The instruction that caused the trap is restarted.

7. Page Replacement Algorithms

When a page fault occurs and there are no free frames available, the OS must free a frame by writing its contents to swap space and changing the page table. This is Page Replacement.

The goal is to select a "victim" frame that minimizes the page-fault rate.

1. FIFO (First-In-First-Out)

- Logic: Replace the oldest page in memory.

- Pros: Easy to understand and program.

- Cons: Performance is not always good.

- Belady’s Anomaly: Increasing the number of frames may actually increase the number of page faults in FIFO.

2. Optimal Page Replacement

- Logic: Replace the page that will not be used for the longest period of time.

- Pros: Guarantees the lowest possible page-fault rate for a fixed number of frames.

- Cons: Impossible to implement in practice because it requires future knowledge of the reference string. Used primarily for comparison/benchmarking.

3. LRU (Least Recently Used)

- Logic: Replace the page that has not been used for the longest period of time. (Approximation of Optimal).

- Implementation: Requires hardware support (counters or stack) to track when pages were last accessed.

- Pros: Good performance; does not suffer from Belady's Anomaly.

- Cons: High overhead to maintain the history.

Summary of Differences

| Feature | Paging | Segmentation |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation | Non-contiguous (Fixed size) | Non-contiguous (Variable size) |

| Fragmentation | Internal Fragmentation | External Fragmentation |

| User View | Invisible to user | Visible (based on logic) |

| Size | Hardware determined | User determined |