Unit 6 - Notes

Unit 6: Quality Management, Maintenance & Emerging Technologies

1. Quality Management & Standards

Software Quality Management (SQM) ensures that the required level of quality is achieved in a software product. It involves defining appropriate quality standards and procedures and ensuring that these are followed.

ISO 9001 (International Organization for Standardization)

ISO 9001 is a generic standard that applies to any organization, but it is widely used in the software industry to ensure quality assurance in design, development, production, installation, and servicing.

- Core Principles:

- Customer Focus: Understanding current and future customer needs.

- Process Approach: Managing activities and resources as a process.

- Continual Improvement: A permanent objective of the organization.

- Evidence-based Decision Making: Analysis of data and information.

- Relevance to Software: While ISO 9001 is generic, ISO 9000-3 provided specific guidelines for applying ISO 9001 to software development, later replaced by ISO/IEC 90003.

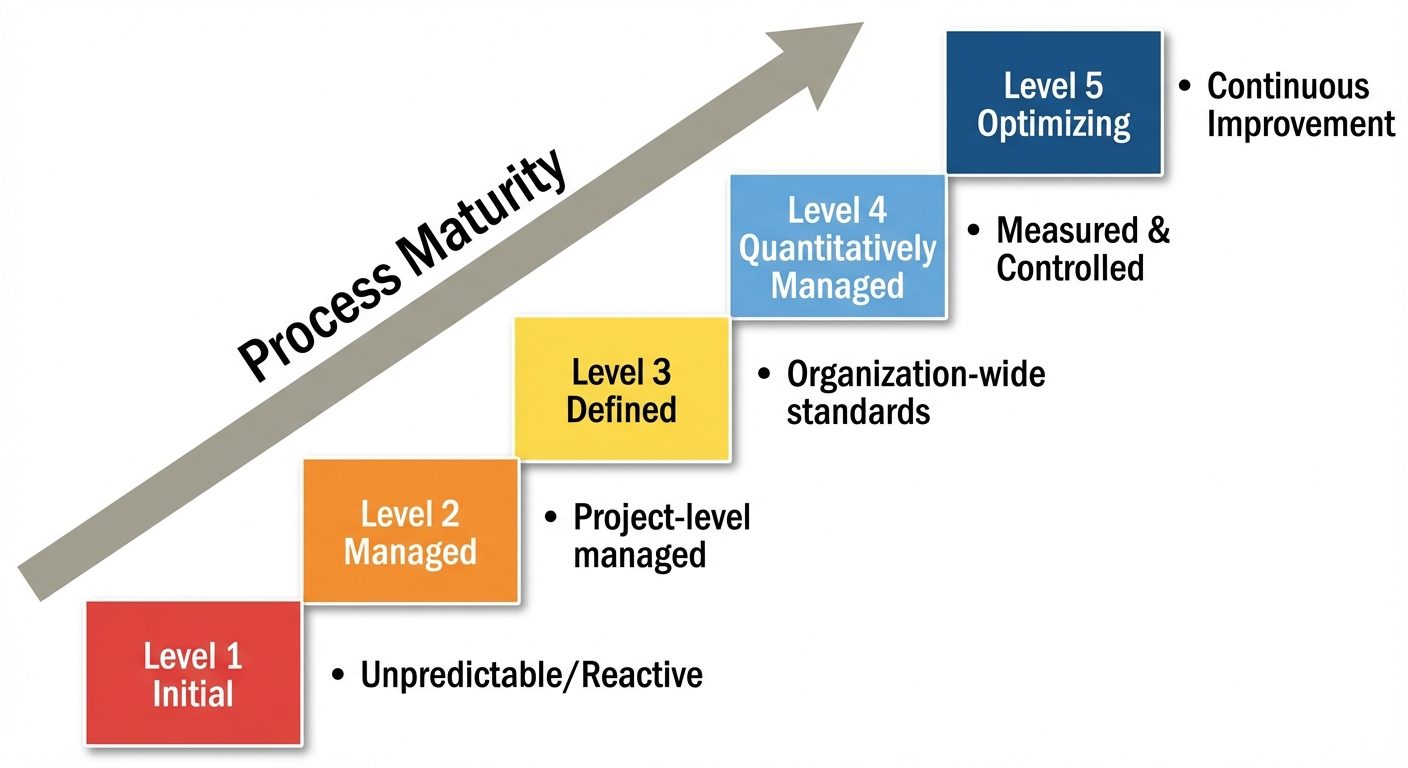

SEI CMMI (Capability Maturity Model Integration)

Developed by the Software Engineering Institute (SEI), CMMI is a process improvement training and appraisal program. It defines five maturity levels for processes:

- Level 1: Initial (Chaotic)

- Processes are unpredictable, poorly controlled, and reactive.

- Success depends on individual heroics rather than established processes.

- Level 2: Managed

- Processes are characterized for projects and is often reactive.

- Basic project management is in place to track cost and schedule.

- Level 3: Defined

- Processes are characterized for the organization and are proactive.

- Standard processes are established and improved over time.

- Level 4: Quantitatively Managed

- Processes are measured and controlled.

- Quantitative data is used to predict process performance.

- Level 5: Optimizing

- Focus on continuous process improvement.

- Innovations and feedback are used to optimize processes.

Six Sigma

Six Sigma is a data-driven approach for eliminating defects in any process.

- Goal: To achieve 3.4 defects per million opportunities (DPMO).

- Methodologies:

- DMAIC: For improving existing processes (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control).

- DMADV: For designing new processes/products (Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify).

PSP (Personal Software Process)

PSP is a structured software development process that is intended to help software engineers understand and improve their own performance.

- Focus: Individual level (unlike CMMI which is organizational).

- Key Activities:

- Time Recording: Tracking time spent on different phases.

- Defect Recording: Logging every defect found and when it was injected/removed.

- Planning: Estimating size and time based on historical data.

2. Computer-Aided Software Engineering (CASE) Tools

CASE tools are software applications used to automate SDLC activities. They reduce the effort required to produce a work product and improve the quality of the product.

Classification of CASE Tools

- Upper CASE Tools:

- Support the early stages of the SDLC (Planning, Analysis, Design).

- Examples: Diagramming tools (Lucidchart), Requirement analysis tools.

- Lower CASE Tools:

- Support the later stages (Implementation, Testing, Maintenance).

- Examples: Compilers, Debuggers, Code generators, Static Analysis tools.

- Integrated CASE (I-CASE):

- Offer a seamless flow of information between Upper and Lower CASE tools.

- Example: Modern IDEs (Visual Studio, IntelliJ) with plugin ecosystems that cover design through deployment.

Benefits:

- Standardization of notations.

- improved documentation quality.

- Faster prototyping and development.

3. Software Maintenance

Software maintenance is the process of modifying a software system or component after delivery to correct faults, improve performance, or adapt to a changed environment.

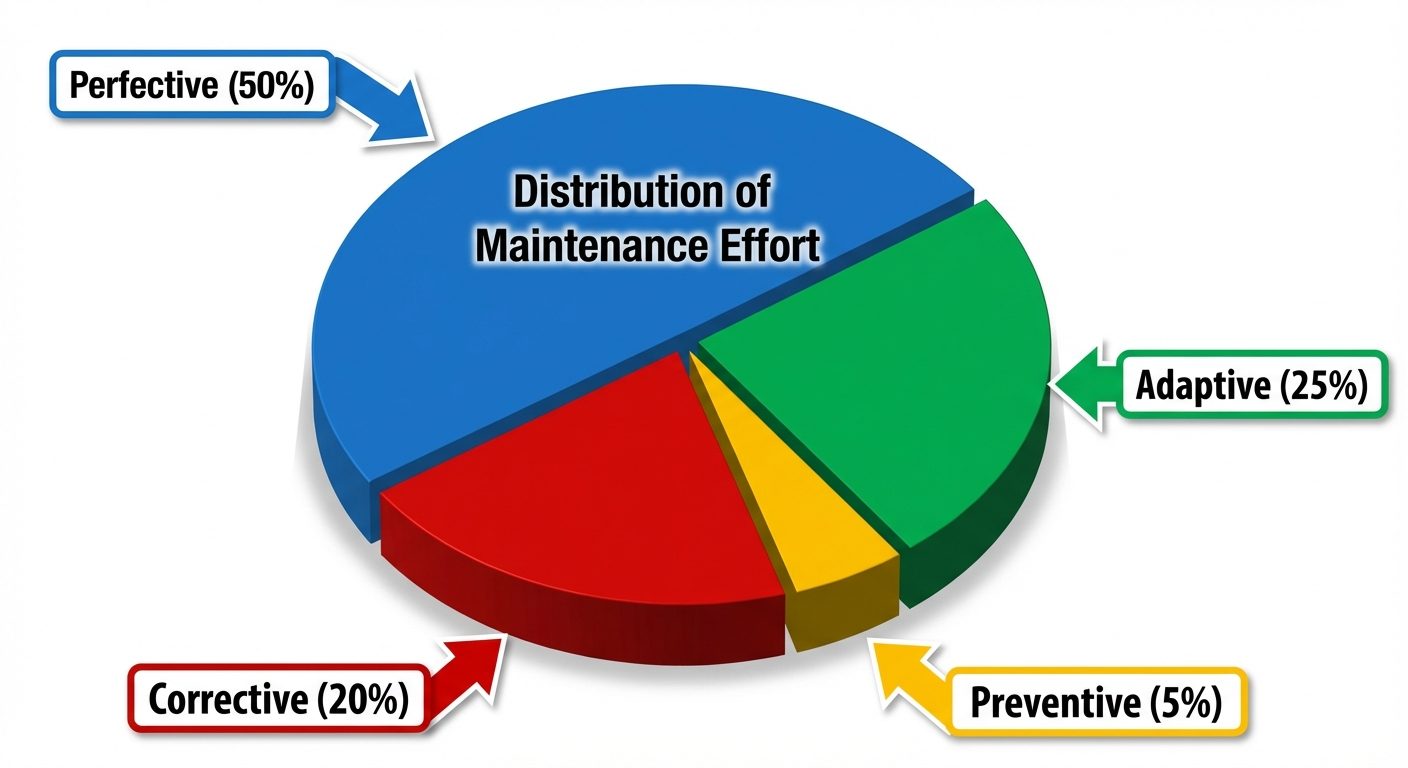

Types of Maintenance

- Corrective Maintenance (approx. 20%):

- Fixing errors and bugs reported by users after deployment.

- "Emergency repairs."

- Adaptive Maintenance (approx. 25%):

- Modifying software to work in a new or changed environment (e.g., OS upgrade, new hardware, new compiler).

- Perfective Maintenance (approx. 50% - The Largest Portion):

- Implementing new functional or non-functional requirements.

- Improving performance or user interface based on user requests.

- Preventive Maintenance (approx. 5%):

- Software Re-engineering.

- Making changes to prevent future problems (e.g., refactoring code to improve maintainability).

Challenges in Software Maintenance

- Legacy Code: Old code often lacks documentation and structure ("Spaghetti code").

- Personnel Turnover: The original developers are often unavailable, requiring new staff to learn the system from scratch.

- Cost: Maintenance is the most expensive phase of the SDLC (often 60-80% of total lifecycle cost).

- Regression: Fixing one bug may introduce new bugs in other parts of the system.

4. Software Reuse & Component-Based Software Development (CBSD)

Software Reuse

The use of existing software artifacts (code, designs, test cases, documentation) to build new software.

- Levels of Reuse:

- Code Reuse: Libraries, classes, functions.

- Design Reuse: Design patterns, architectural patterns.

- Application Reuse: COTS (Commercial Off-The-Shelf) software.

Component-Based Software Development (CBSD)

CBSD focuses on building large software systems by integrating pre-existing software components.

- Component Definition: A self-contained unit of composition with contractually specified interfaces and explicit context dependencies only.

- Key Characteristics:

- Independent: Components can be deployed independently.

- Standardized: Must adhere to component models (e.g., JavaBeans, .NET, COM).

- Black-box: Internal implementation is hidden; interaction occurs only via interfaces.

- CBSD Lifecycle:

- Requirements gathering.

- Component search and selection (Buy vs. Build).

- Component adaptation (wrapping/bridging).

- System integration.

5. Advanced and Future Techniques

Cloud-Native Software Development

An approach to building and running applications that exploits the advantages of the cloud computing delivery model.

- Microservices: Breaking monolithic apps into loosely coupled services.

- Containers: Packaging code and dependencies together (e.g., Docker) for consistency across environments.

- DevOps & CI/CD: Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment pipelines automate delivery.

- Scalability: Applications can auto-scale horizontally based on demand.

AI in Software Development (AI-Assisted SE)

The integration of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning into the software engineering workflow.

- Generative AI Coding Assistants:

- GitHub Copilot / Amazon CodeWhisperer: These tools use Large Language Models (LLMs) trained on billions of lines of public code.

- Functionality: They suggest whole lines or functions of code, write unit tests, and translate code between languages.

- Benefits:

- Increased developer velocity.

- Reduction in boilerplate coding tasks.

- Assistance with syntax and API discovery.

- Challenges:

- Security: AI might suggest insecure code patterns.

- IP/Copyright: Legal concerns regarding the training data used for the models.

- Over-reliance: Developers may approve code they do not fully understand.

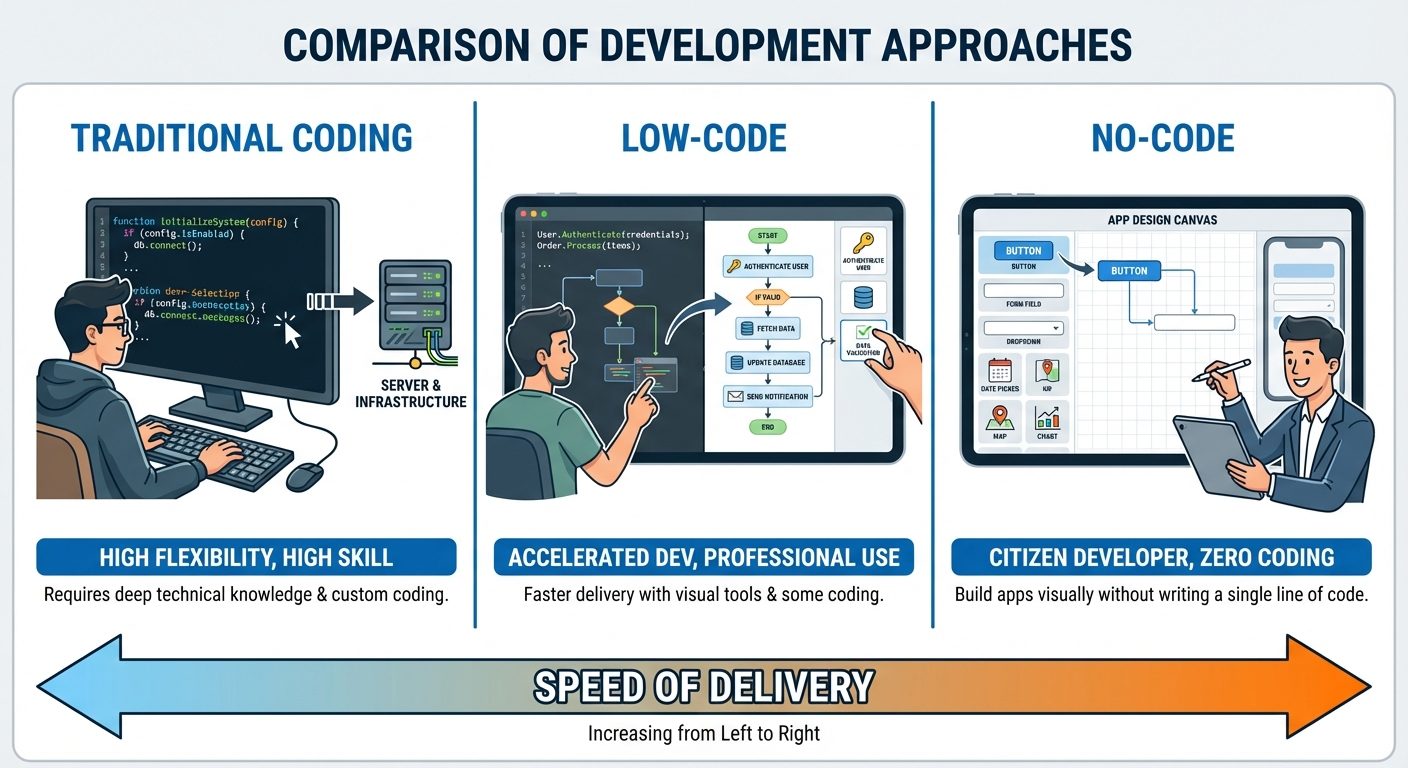

Low-Code / No-Code Platforms

Development platforms that allow the creation of application software through graphical user interfaces and configuration instead of traditional computer programming.

- No-Code: Targeted at "Citizen Developers" (business users). purely visual, drag-and-drop. Good for simple apps.

- Low-Code: Targeted at professional developers. Requires some coding for complex logic but automates standard CRUD operations and UI design.

- Examples: Mendix, OutSystems, Microsoft PowerApps, Bubble.