Unit 4 - Notes

Unit 4: Quantum Mechanics

1. Need for Quantum Mechanics

Classical mechanics (Newtonian mechanics) successfully explains macroscopic phenomena (motion of planets, projectiles, etc.). However, toward the end of the 19th century, it failed to explain microscopic phenomena involving atomic and sub-atomic particles.

Key Failures of Classical Mechanics:

- Blackbody Radiation: Classical theory (Rayleigh-Jeans Law) predicted "Ultraviolet Catastrophe"—that an ideal blackbody would emit infinite energy at high frequencies. Max Planck resolved this by assuming energy is quantized ().

- Photoelectric Effect: Classical wave theory could not explain why light below a certain frequency failed to eject electrons regardless of intensity, or why emission was instantaneous.

- Atomic Stability: According to classical electromagnetism, an accelerating electron in an orbit should radiate energy and spiral into the nucleus. This contradicted the observed stability of atoms.

- Atomic Spectra: Classical physics could not explain the discrete line spectra observed in hydrogen and other elements.

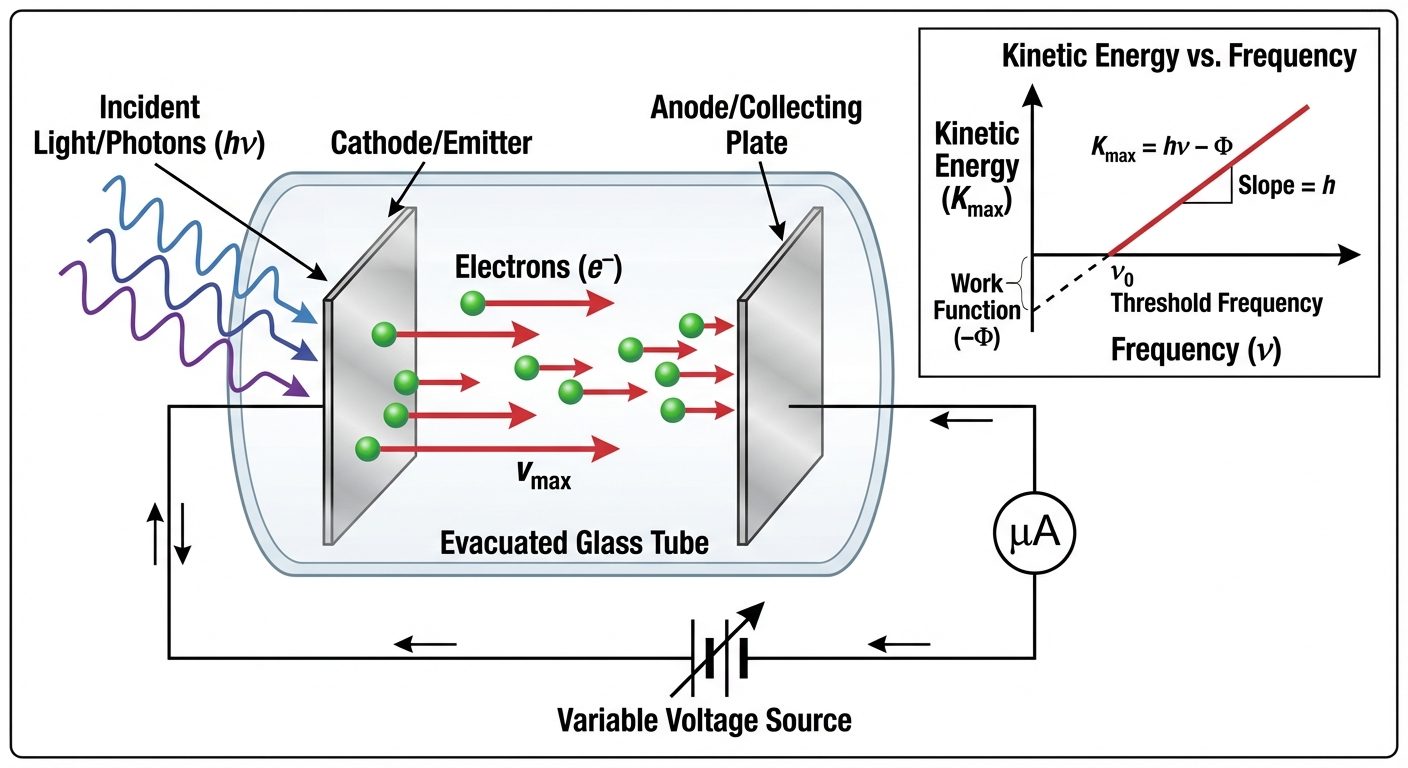

2. Photoelectric Effect

The phenomenon of the emission of electrons from the surface of a metal when electromagnetic radiation (light) of suitable frequency falls on it is called the photoelectric effect.

Experimental Observations:

- Threshold Frequency (): For a given metal, there exists a minimum frequency of incident light below which no emission occurs, regardless of intensity.

- Instantaneous Process: There is no detectable time lag between the incidence of light and emission of photoelectrons ( s).

- Kinetic Energy: The maximum kinetic energy of emitted electrons depends linearly on the frequency of incident light, not its intensity.

- Saturation Current: The number of photoelectrons (photocurrent) is directly proportional to the intensity of incident light (provided ).

Einstein’s Photoelectric Equation:

Einstein applied Planck's quantum theory, suggesting light consists of discrete packets of energy called photons ().

Where:

- : Energy of incident photon.

- (Work Function): Minimum energy required to pull an electron out of the metal surface ().

- : Maximum kinetic energy of the emitted electron ().

Rearranging:

3. De Broglie Matter Waves

In 1924, Louis de Broglie hypothesized the Wave-Particle Duality. He suggested that if nature is symmetrical, and radiation (light) has a dual nature (wave and particle), then matter (particles like electrons, protons) should also possess a dual nature.

Concept:

A moving material particle is associated with a wave, known as a Matter Wave or de Broglie Wave. These waves are pilot waves that guide the particle.

De Broglie Wavelength ():

Where is Planck's constant, is momentum, is mass, and is velocity.

Wavelength of Matter Waves in Different Forms

-

In terms of Kinetic Energy ():

-

For a Charged Particle accelerated by Potential ():

If a particle with charge is accelerated through a potential difference , the work done equals kinetic energy ().

-

Specifically for an Electron:

Substituting constants ( kg, C, Js):

-

For Gas Molecules (Thermal Neutrons) at Temperature :

Average kinetic energy (where is Boltzmann's constant).

4. Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

Proposed by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, this principle is a direct consequence of the wave nature of matter.

Statement:

It is impossible to determine simultaneously both the exact position and the exact momentum (or velocity) of a microscopic particle.

Mathematical Expression:

Where:

- : Uncertainty in position.

- : Uncertainty in momentum.

- : Reduced Planck's constant.

Alternative Forms:

- Energy-Time Uncertainty:

- Angular Displacement-Angular Momentum:

Significance:

- It sets a fundamental limit to measurement precision, independent of instrument quality.

- It explains the non-existence of electrons inside the nucleus (confinement requires energy higher than observed).

- It explains the zero-point energy of oscillators (a particle cannot be at complete rest).

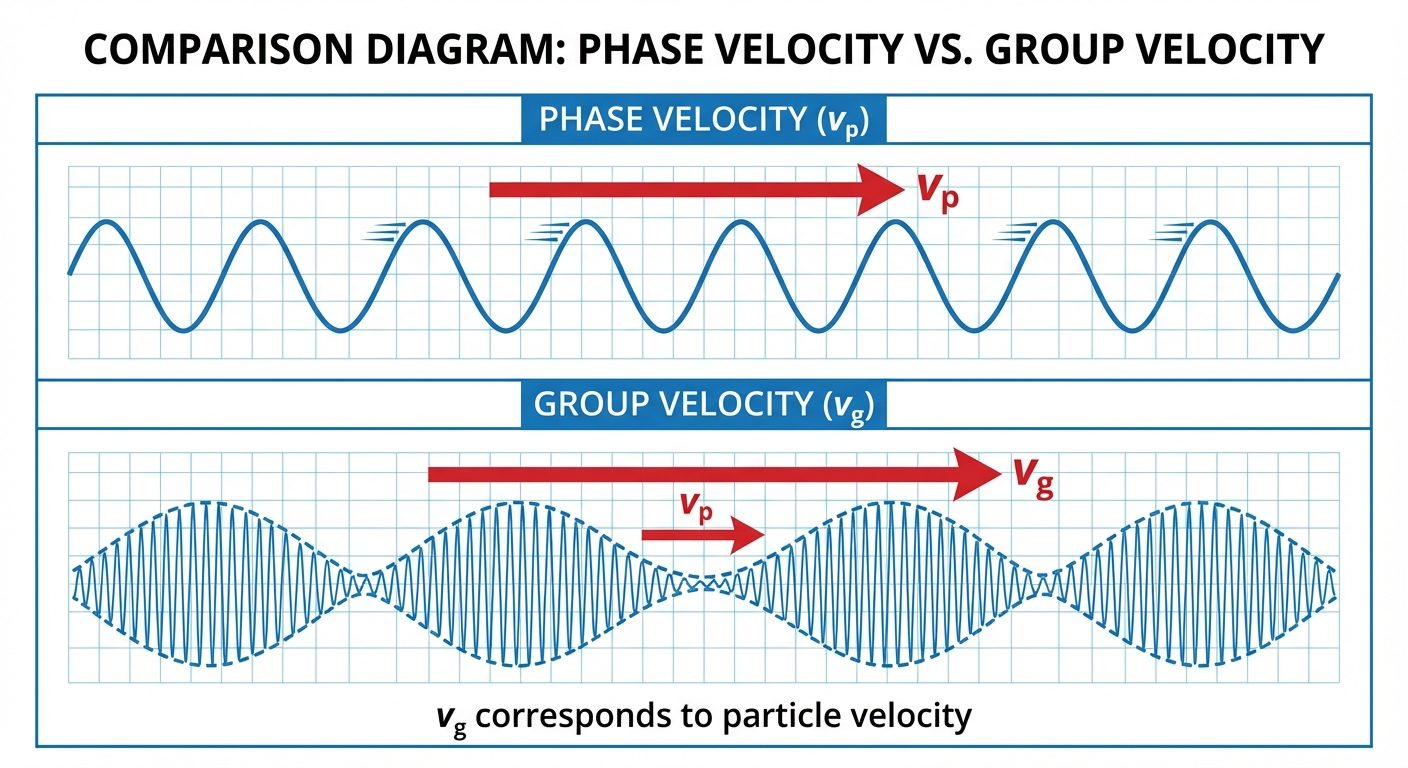

5. Phase Velocity and Group Velocity (Qualitative)

Since a particle is localized in space but a pure sine wave extends infinitely, a single wave cannot represent a particle. Instead, a particle is represented by a Wave Packet formed by the superposition of multiple waves of slightly different frequencies.

Phase Velocity ():

- The velocity with which a definite monochromatic wave (single frequency) travels through a medium.

- Formula:

- Problem: For matter waves, . Since particle velocity , then . This carries no physical information, so it does not violate relativity.

Group Velocity ():

- The velocity with which the envelope of the wave packet (the region of maximum amplitude) travels.

- It represents the velocity of energy transport or the particle itself.

- Formula:

- Relation: For a non-relativistic particle, the group velocity of the matter wave is equal to the classical velocity of the particle ().

6. Wave Function and its Significance

Wave Function ():

The wave function is a mathematical variable that characterizes the state of a quantum mechanical system. It contains all the information that can be known about the system.

Physical Significance (Max Born Interpretation):

- itself has no direct physical meaning. It can be a complex quantity ().

- Probability Density: The square of the modulus of the wave function, , represents the probability of finding the particle at a specific point in space and time.

- Normalization: The total probability of finding the particle somewhere in the universe must be 1.

Conditions for a Well-Behaved Wave Function:

To be physically acceptable, must be:

- Finite: Must not go to infinity.

- Single-valued: Only one probability value per location.

- Continuous: and its first derivative must be continuous everywhere.

7. Schrödinger Equation

Erwin Schrödinger developed a differential equation that describes how the quantum state of a physical system changes over time. It plays the same role in Quantum Mechanics as Newton's laws in Classical Mechanics.

A. Schrödinger Time-Dependent Wave Equation (TDSE)

Describes the evolution of the wave function with time.

Or in operator form: (Total Energy operator = Hamiltonian operator).

B. Schrödinger Time-Independent Wave Equation (TISE)

Used for stationary states where the potential depends only on position, not time.

For 1-Dimension:

Where:

- : Space-dependent part of wave function.

- : Total energy.

- : Potential energy.

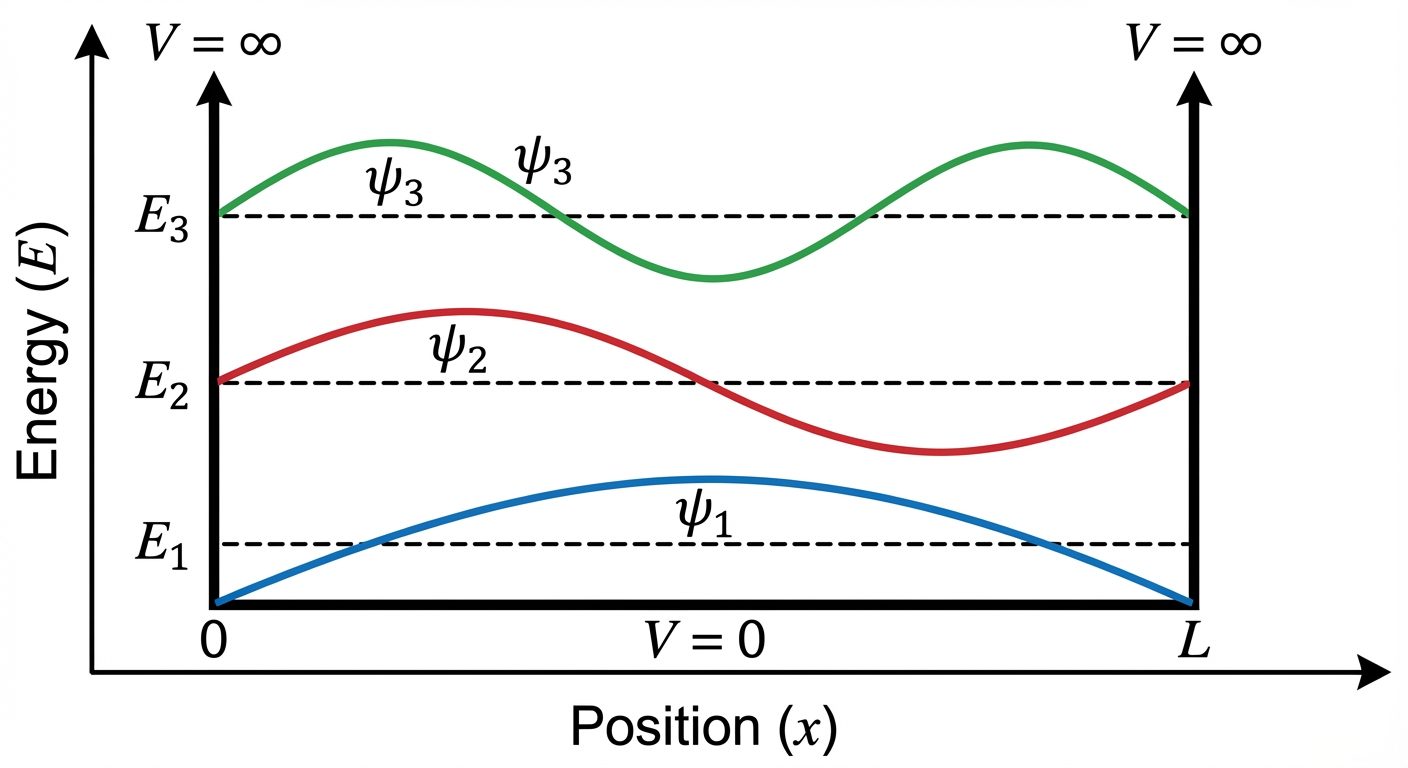

8. Particle in a One-Dimensional Box (Infinite Potential Well)

This is the simplest application of the Schrödinger equation, demonstrating energy quantization.

System Description:

- A particle of mass moves in a 1D box of length (from to ).

- Potential :

- for (Free motion inside).

- for and (Impenetrable walls).

Boundary Conditions:

Since the particle cannot exist outside the box (infinite potential), and .

Solution:

Solving the Time-Independent Schrödinger equation for :

Where (Quantum number).

Energy Eigenvalues:

Applying boundary conditions yields quantized energy levels:

Key Conclusions:

- Discrete Energy: Energy can only take specific discrete values (). It is not continuous.

- Zero-Point Energy: The lowest energy () is . It is not zero, consistent with the Uncertainty Principle.

- Nodes: The number of nodes (points where probability is zero) increases with .

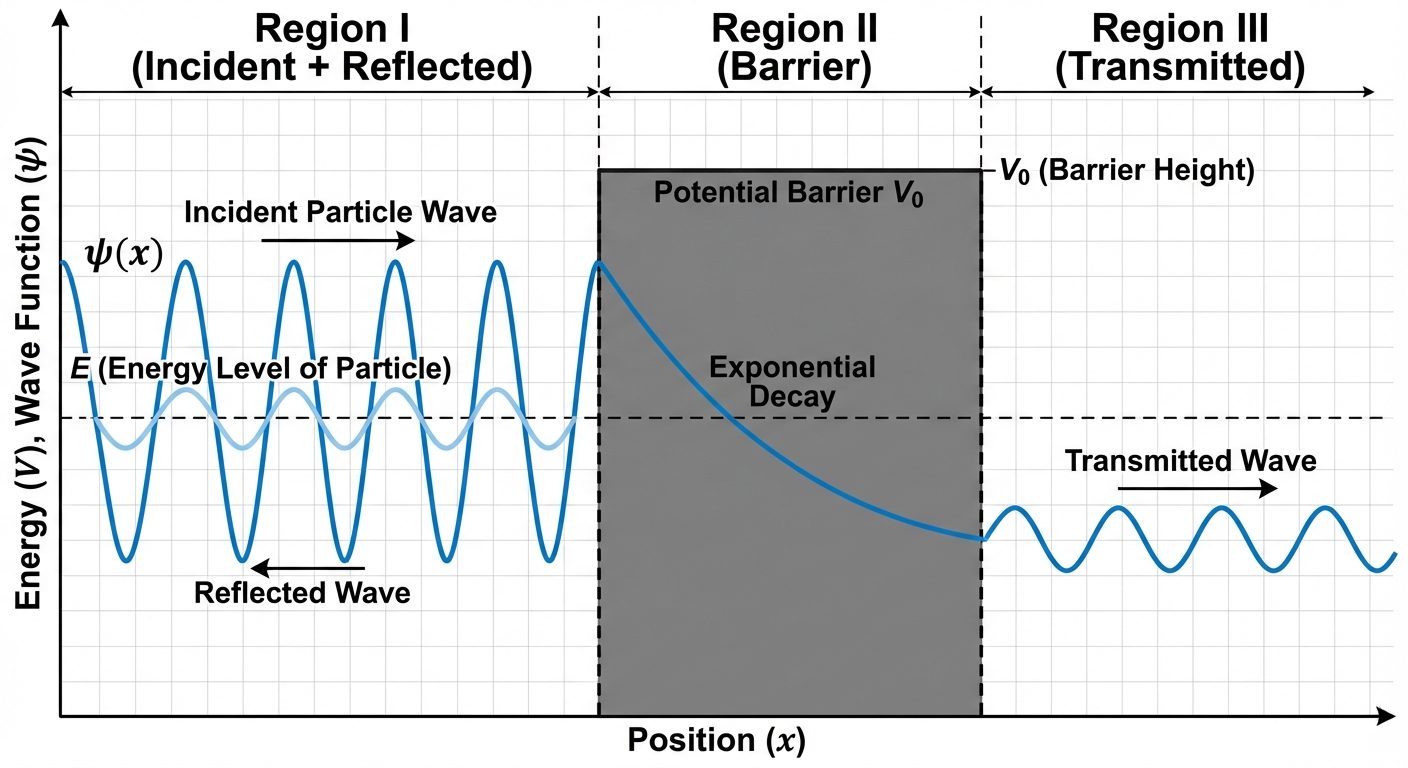

9. Tunneling Effect (Qualitative Idea)

Tunneling is a purely quantum mechanical phenomenon where a particle penetrates through a potential energy barrier that represents a higher energy than the particle's kinetic energy.

Classical View:

If a particle with energy approaches a potential barrier of height where , it will bounce back. Crossing is impossible.

Quantum View:

- The wave function does not drop to zero immediately at the barrier boundary.

- Instead, it decays exponentially inside the barrier region.

- If the barrier is thin enough, the wave function will emerge on the other side with a non-zero amplitude.

- This means there is a finite probability () that the particle will be found on the other side.

Applications:

- Alpha Decay: Explains how alpha particles escape the nuclear potential well despite having insufficient energy.

- Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM): Uses electron tunneling to image surfaces at the atomic level.

- Tunnel Diode: A semiconductor device utilizing tunneling for high-speed switching.