Unit 3 - Notes

CSC203

Unit 3: Basic Distributed Computing and Cryptography

1. Atomic Broadcast and Consensus

In distributed systems like blockchain, ensuring that all participants (nodes) agree on a specific state or sequence of events is crucial. This is achieved through Atomic Broadcast and Consensus protocols.

Atomic Broadcast

Atomic broadcast (often called Total Order Multicast) is a communication primitive used in distributed systems to ensure that messages are delivered reliably and in the same order to all participants.

- Definition: A protocol where if a message is sent to a group of processes, either all correct processes deliver the message, or none do (Atomicity), and all processes deliver the set of messages in the exact same sequence (Total Order).

- Key Properties:

- Validity: If a correct process broadcasts a message , then all correct processes eventually deliver .

- Uniform Agreement: If a process delivers message , then all correct processes eventually deliver .

- Uniform Integrity: A message is delivered at most once per process, and only if it was broadcast.

- Total Order: If processes and both deliver messages and , then delivers before if and only if delivers before .

- Role in Blockchain: Atomic broadcast is equivalent to consensus. In a blockchain, the "messages" are transactions or blocks. The network must ensure every node appends the same block in the same position in the chain.

Consensus

Consensus is the process by which a network of unreliable nodes reaches an agreement on a specific data value or state of the network.

- The Problem: Nodes may crash, messages may be lost/delayed, or nodes may act maliciously (Byzantine faults). The system must still reach a decision.

- FLP Impossibility: The Fisher-Lynch-Paterson theorem states that in an asynchronous network (where message timing is unpredictable), it is impossible to guarantee consensus if even a single node can crash (fail-stop). Blockchains solve this by using probabilistic finality or synchronous assumptions (timeouts).

- Standard Properties Required:

- Termination: Every correct node eventually decides on a value.

- Agreement: All correct nodes decide on the same value.

- Validity: If all correct nodes propose the same value , then the decided value must be .

2. Byzantine Models of Fault Tolerance

Distributed systems must handle failures. The most severe type of failure is a Byzantine Failure, where a component acts arbitrarily, maliciously, or sends conflicting information to different parts of the system.

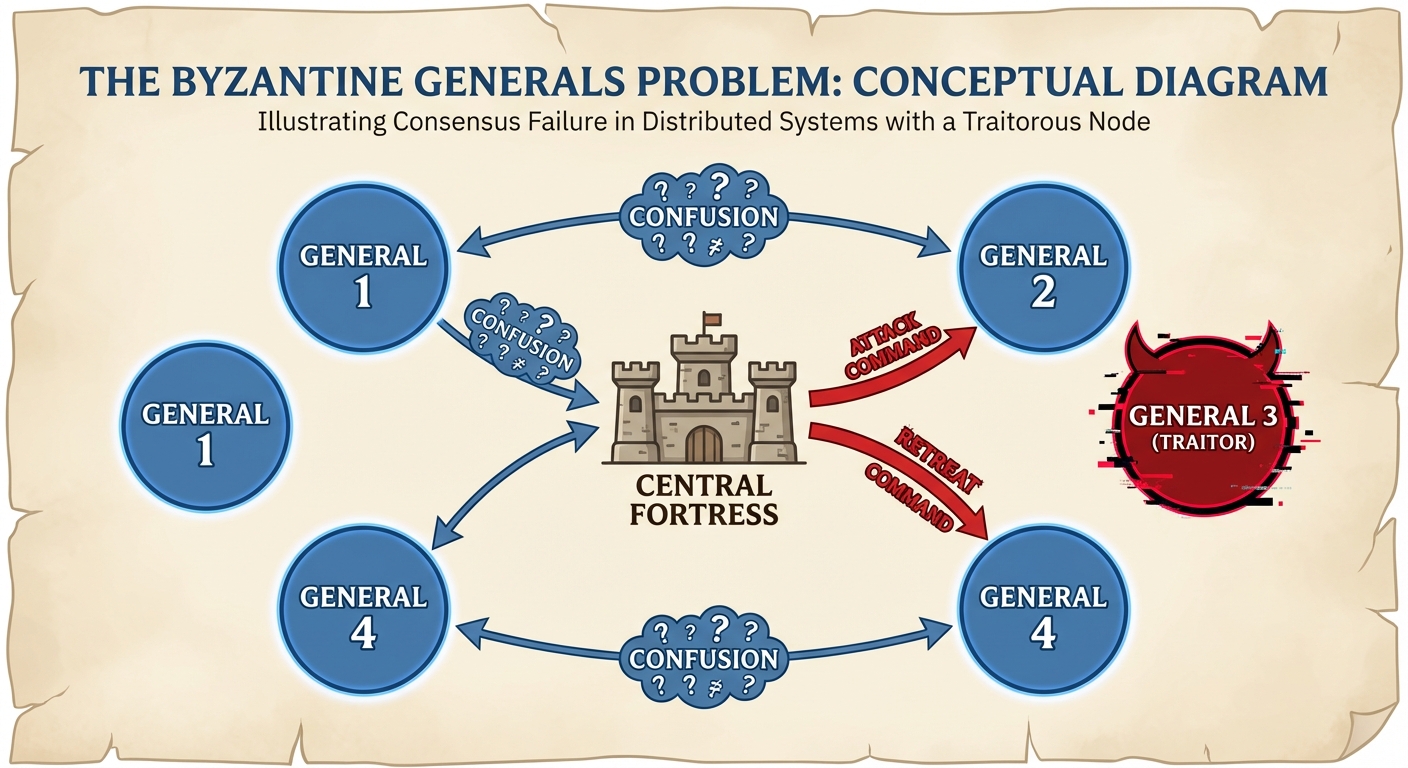

The Byzantine Generals Problem

This is a logical dilemma illustrating how a group of separated generals must agree on a battle plan (Attack or Retreat) while communicating only via messengers, knowing that some generals (nodes) may be traitors (malicious).

- Scenario: Generals encompass a city. They must attack simultaneously to win. If only some attack, they die. They must agree on a consensus.

- The Traitor: A traitorous general might tell General A "Attack" and General B "Retreat" to cause chaos.

- The Constraint: It is proven that for a system to reach consensus in the presence of Byzantine (malicious) nodes, the total number of nodes must be at least .

- Mathematical requirement: .

Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT)

BFT is the property of a system that is able to resist the class of failures derived from the Byzantine Generals Problem.

- Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT): A popular algorithm optimized for low latency. It relies on a state machine replication where nodes cycle through views (Pre-prepare, Prepare, Commit).

- Pros: High throughput, low energy usage.

- Cons: High communication overhead (scales poorly as node count increases).

- Blockchain Application:

- PoW (Proof of Work): Uses probabilistic BFT via mining power (Nakamoto Consensus). Requires 51% honest computing power.

- Tendermint / Cosmos: Uses classic BFT voting mechanisms requiring 2/3rds honest validators.

3. Cryptographic Hash Functions

A cryptographic hash function is a mathematical algorithm that maps data of an arbitrary size to a bit string of a fixed size (the hash). It is a one-way function.

Basic Properties

- Determinism: The same input always results in the same output.

- Avalanche Effect: A tiny change in the input (e.g., flipping one bit) results in a drastically different output hash.

- Pre-image Resistance (One-way): Given a hash , it is computationally infeasible to determine the original input .

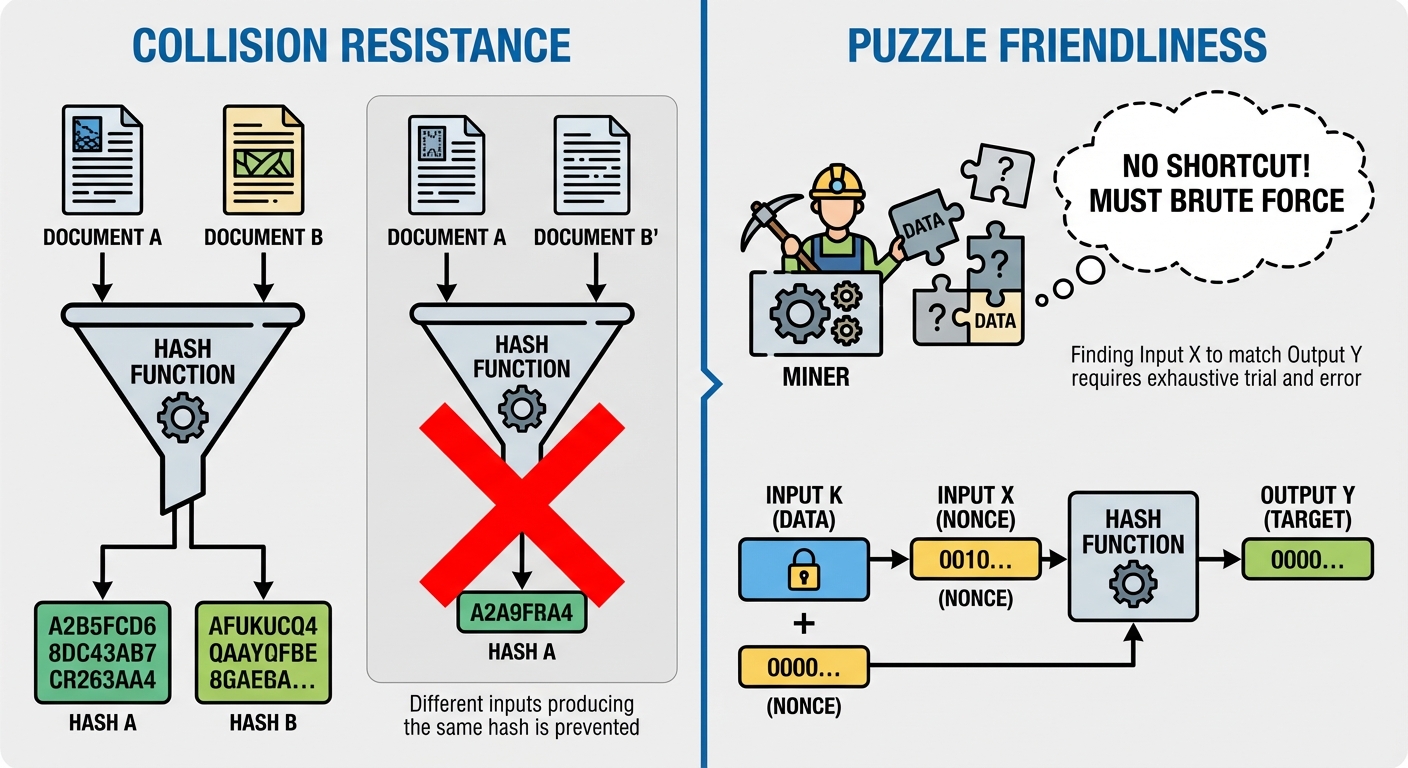

Collision Resistant Hash

A collision occurs when two distinct inputs produce the same output hash: but .

- Collision Resistance Definition: A hash function is collision-resistant if it is computationally infeasible to find any two distinct inputs and that hash to the same result.

- Importance in Blockchain:

- Addresses and transaction IDs rely on unique hashes.

- Merkle Trees rely on collision resistance to ensure data integrity. If collisions were easy, a bad actor could substitute fake transaction data that produces the same Merkle root.

- Birthday Paradox: The probability of finding a collision increases faster than one might intuitively expect as the number of inputs increases, dictating the necessary bit-length of the hash (e.g., SHA-256).

Puzzle Friendly Hash

This property is specifically required for cryptocurrency mining (Proof of Work).

- Definition: A hash function is puzzle-friendly if, for every possible -bit output value , if is chosen from a distribution with high min-entropy (unpredictable), it is infeasible to find such that significantly faster than operations.

- Implication: In simple terms, there are no shortcuts. To find a hash that meets a specific difficulty target (e.g., starts with 10 zeros), the miner must brute-force the solution by trying random nonces. Knowing the previous block hash doesn't help predict the nonce for the current block.

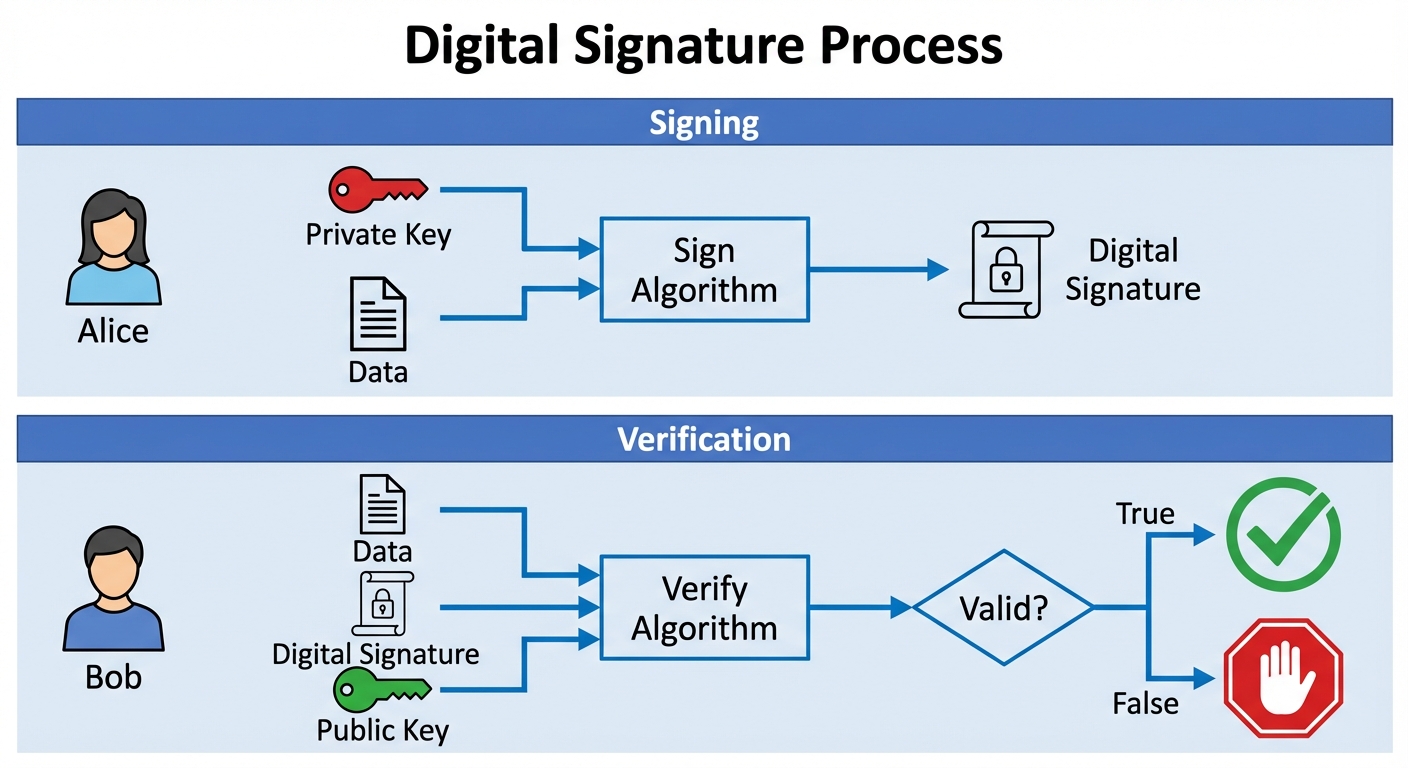

4. Digital Signatures

Digital signatures serve as the digital equivalent of a handwritten signature or a stamped seal, but with far higher security guarantees. They use asymmetric cryptography (Public/Private key pairs).

Core Mechanisms

- Key Generation: A user generates a pair . is the Secret/Private Key (kept safe), is the Public Key (shared).

- Signing (): The sender calculates a signature . The signature depends on both the specific message and the private key.

- Verification (): The receiver checks validity using . It outputs True or False.

Properties

- Authentication: The receiver can verify the sender is who they claim to be (owner of the private key).

- Integrity: The message has not been altered in transit. If the message changes, the signature becomes invalid.

- Non-repudiation: The signer cannot deny having signed the message later, as only they possess the private key.

Blockchain Usage

- Authorizing transactions: Sending Bitcoin requires signing the transaction with the private key associated with the wallet address.

- Algorithms used: ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) used in Bitcoin/Ethereum; Ed25519 used in Solana/Cardano.

5. Verifiable Random Functions (VRF)

In many blockchain protocols (especially Proof of Stake), generating random numbers securely is difficult. If the random number generation (RNG) is predictable, validators can game the system to be selected as block leaders.

Definition

A VRF is a cryptographic primitive that maps an input to a verifiable pseudorandom output. It is essentially a random number generator that provides a cryptographic proof that the number was generated correctly.

Components

- Input: A seed value (public) and a Private Key ().

- Output: A Random Value () and a Proof ().

- Function: .

Verification

Any user with the Public Key () can check that corresponds to the using the Proof , without knowing the Private Key.

- Verify() True/False.

Application

- Algorand: Uses VRF to secretly select committees for consensus. Users run a lottery locally; if they win, they submit the proof.

- Preventing Grinding Attacks: Attackers cannot try different inputs to get a favorable random outcome because the output is deterministic based on their private key, yet looks random to everyone else.

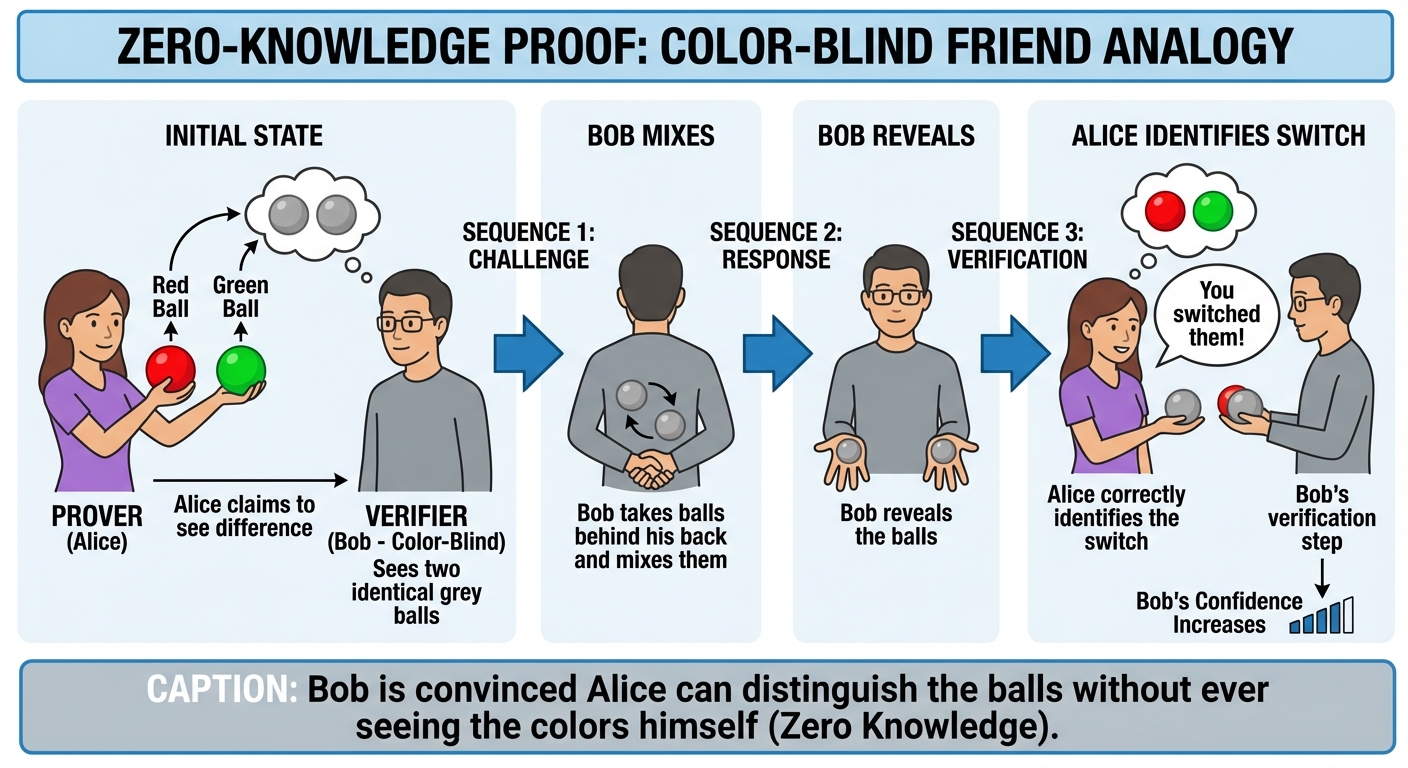

6. Zero-Knowledge Systems

Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) allow one party (the Prover) to prove to another party (the Verifier) that they know a specific value or that a statement is true, without conveying any additional information apart from the fact that the statement is true.

The Three Properties

- Completeness: If the statement is true and both parties follow the protocol, the verifier will accept the proof.

- Soundness: If the statement is false, a cheating prover cannot convince the verifier that it is true (except with negligible probability).

- Zero-Knowledge: If the statement is true, the verifier learns nothing other than the fact that the statement is true. (They do not learn the secret).

Types of ZKPs

- Interactive ZKP: Requires back-and-forth communication between Prover and Verifier (e.g., Sigma Protocols).

- Non-Interactive ZKP (NIZK): The prover generates a single proof string that the verifier checks. This is essential for blockchains to minimize communication.

- zk-SNARKs (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge): Used in Zcash. Requires a "trusted setup." Very small proof size.

- zk-STARKs (Scalable Transparent Argument of Knowledge): No trusted setup required, quantum resistant, but larger proof sizes.

Blockchain Use Cases

- Privacy: Zcash and Monero allow transactions where the sender, receiver, and amount remain hidden, yet the network verifies the coins exist and haven't been double-spent.

- Scalability (Rollups): ZK-Rollups bundle hundreds of transactions off-chain and submit a single validity proof to the main chain (e.g., Ethereum), reducing gas costs.