Unit 1 - Notes

MTH401

4 min read

Unit 1: Logic and Proofs

1. Propositional Logic

Propositions are declarative statements that are either True (T) or False (F), but not both.

Logical Operators (Connectives)

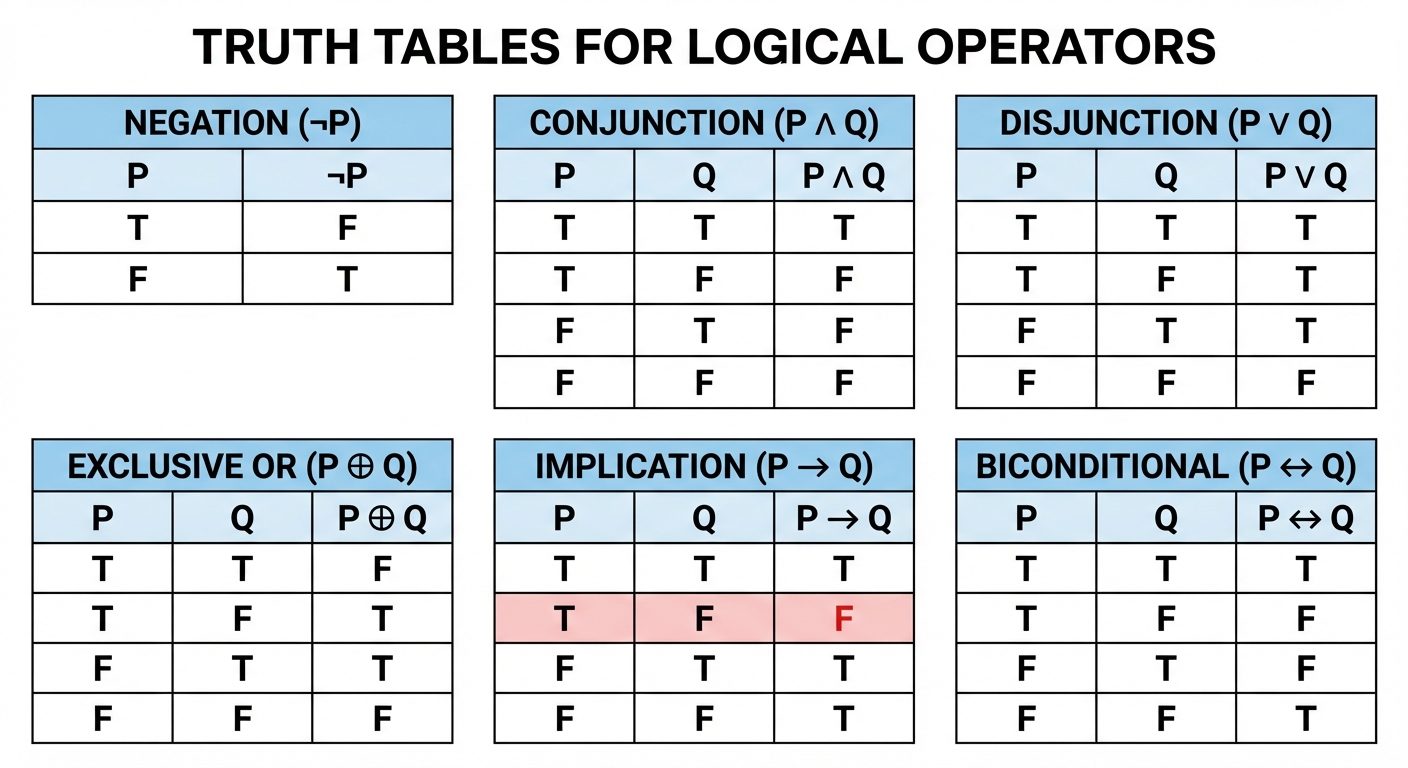

- Negation (): "Not ". Reverses the truth value.

- Conjunction (): "And". True only if both and are true.

- Disjunction (): "Or" (Inclusive). True if at least one is true.

- Exclusive Or (): "XOR". True if exactly one is true, but not both.

- Implication (): "If , then ".

- : Hypothesis/Antecedent.

- : Conclusion/Consequent.

- False only when is True and is False.

- Biconditional (): " if and only if ". True when and share the same truth value.

2. Propositional Equivalences

Two compound propositions are logically equivalent () if they have the same truth values in all possible cases.

Types of Compound Propositions

- Tautology: Always True (e.g., ).

- Contradiction: Always False (e.g., ).

- Contingency: Neither a tautology nor a contradiction.

Key Laws of Logic

- Identity & Domination Laws: ; .

- De Morgan’s Laws:

- Implication Law:

- Contrapositive Law:

3. Predicates and Quantifiers

Predicate Logic deals with statements involving variables. is a propositional function.

Quantifiers

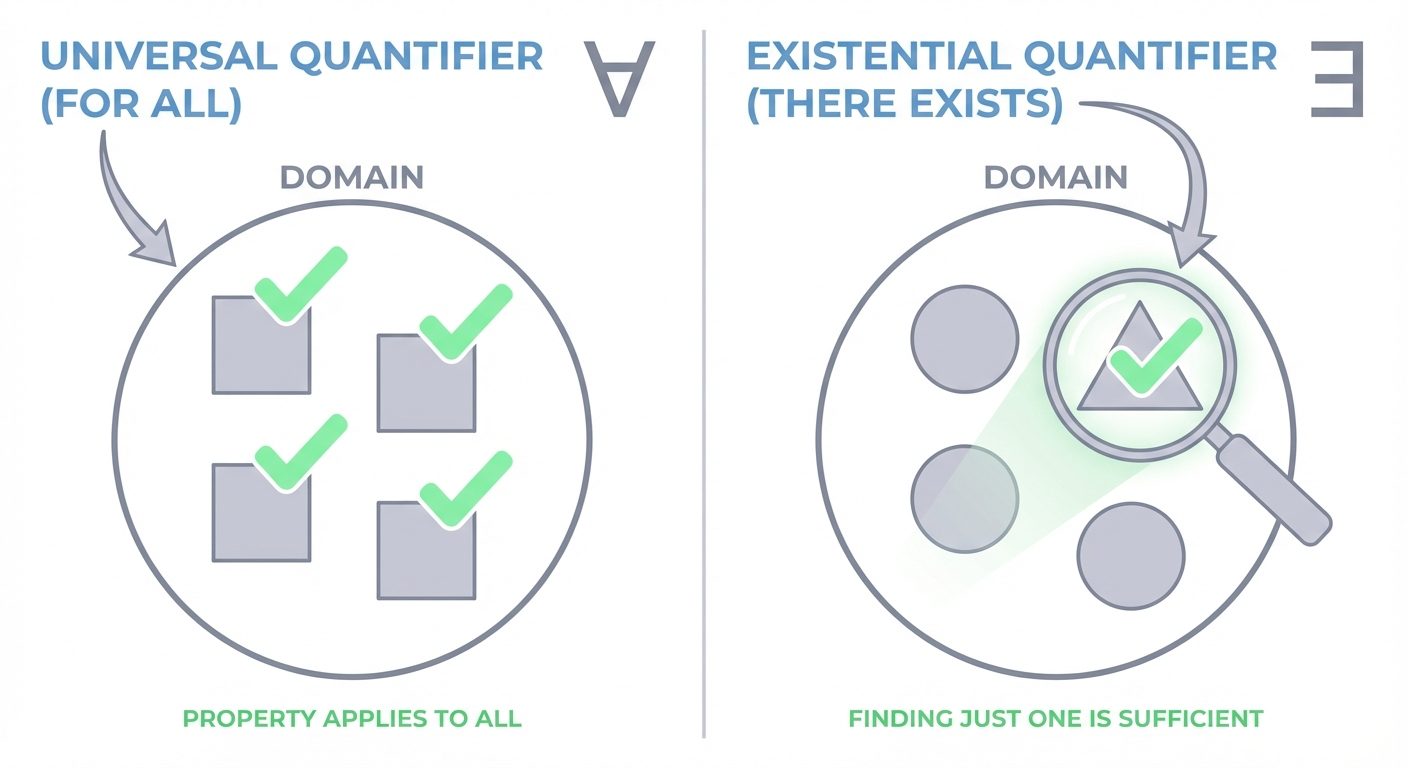

- Universal Quantifier (): "For all , is true."

- True if is valid for every element in the domain.

- False if there is at least one counterexample.

- Existential Quantifier (): "There exists an such that is true."

- True if is valid for at least one element.

- False if is false for every element.

Negating Quantifiers (De Morgan's Laws for Quantifiers)

4. Introduction to Proofs

A proof is a valid argument that establishes the truth of a mathematical statement.

- Theorem: A statement that can be shown to be true.

- Lemma: A helper theorem used to prove a larger theorem.

- Corollary: A result that follows directly from a theorem.

- Conjecture: A statement proposed to be true but not yet proven.

5. Methods of Proof

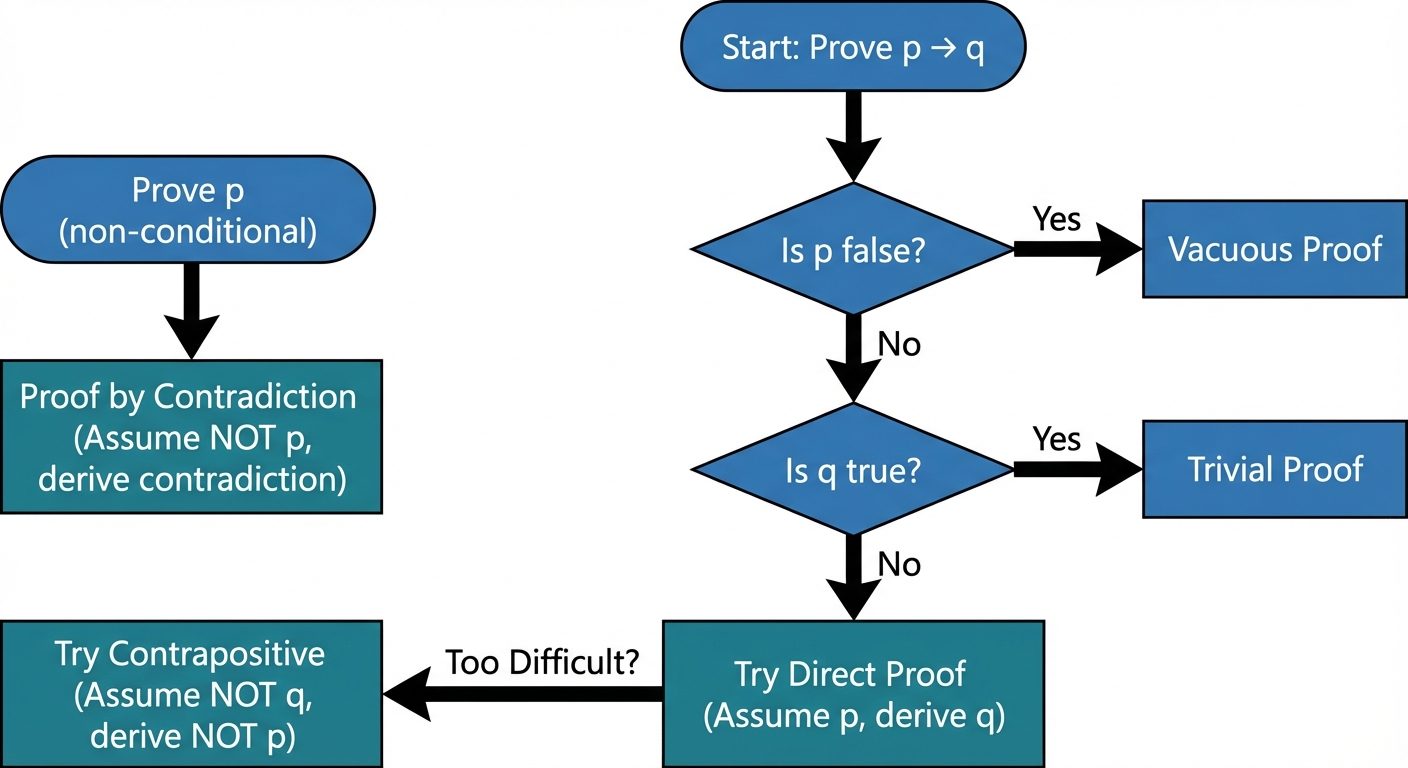

Direct Proof

- Goal: Prove .

- Method: Assume is True. Use axioms, definitions, and logical steps to show that must also be True.

Proof by Contraposition (Indirect)

- Goal: Prove .

- Method: Prove the logically equivalent contrapositive .

- Assume is True (q is false).

- Show that must be True (p is false).

Vacuous and Trivial Proofs

- Vacuous Proof: Used for . If we show is False, the implication is automatically True.

- Trivial Proof: Used for . If we show is True, the implication is automatically True regardless of .

6. Advanced Proof Strategies

Proof by Contradiction

- Goal: Prove proposition is True.

- Method:

- Assume is True (assume the statement is false).

- Derive a logical contradiction (e.g., or ).

- Conclude that since the assumption led to a contradiction, must be False, so is True.

Proof of Equivalence

- Goal: Prove .

- Method: You must prove two parts:

Counterexamples

- Goal: Disprove a universal statement .

- Method: Find a single element in the domain where is False.

7. Mistakes in Proofs (Fallacies)

Common logical errors that invalidate a proof:

- Affirming the Consequent:

- Error: is true, and is true. Therefore, is true. (Invalid)

- Example: "If it rains, the ground is wet. The ground is wet, therefore it rained." (False; could be a sprinkler).

- Denying the Antecedent:

- Error: is true, and is false. Therefore, is false. (Invalid)

- Begging the Question (Circular Reasoning):

- Using the statement you are trying to prove as one of the steps in the proof.