Unit 6 - Notes

Unit 6: Introduction to Engineering Materials

1. Dielectric Materials

1.1 Definition

Dielectric materials are essentially electrical insulators that can be polarized by an applied electric field. Unlike conductors, they do not have free electrons for conduction. When a dielectric is placed in an electric field, electric charges do not flow through the material as they do in a conductor, but only slightly shift from their average equilibrium positions causing dielectric polarization.

Key Characteristics:

- Large energy gap () between the valence and conduction bands.

- Examples: Mica, Glass, Plastic, Ceramics, Distilled Water.

1.2 Dielectric Constant ( or )

The dielectric constant (also known as relative permittivity) is a measure of a material's ability to store electrical energy in an electric field. It is the ratio of the permittivity of the substance () to the permittivity of free space ().

Formula:

Where:

- = Dielectric constant (unitless)

- = Absolute permittivity of the medium

- = Permittivity of free space ()

- = Capacitance with the dielectric material

- = Capacitance with a vacuum/air

Physical Significance:

- A higher dielectric constant indicates that the material can store more electrical charge at a given voltage.

- It reduces the effective electric field within the material due to the induced opposing field created by polarization.

2. Magnetic Materials

Magnetic materials are classified based on their response to an external magnetic field. This response is determined by the magnetic susceptibility () and relative permeability ().

2.1 Classification of Magnetic Materials

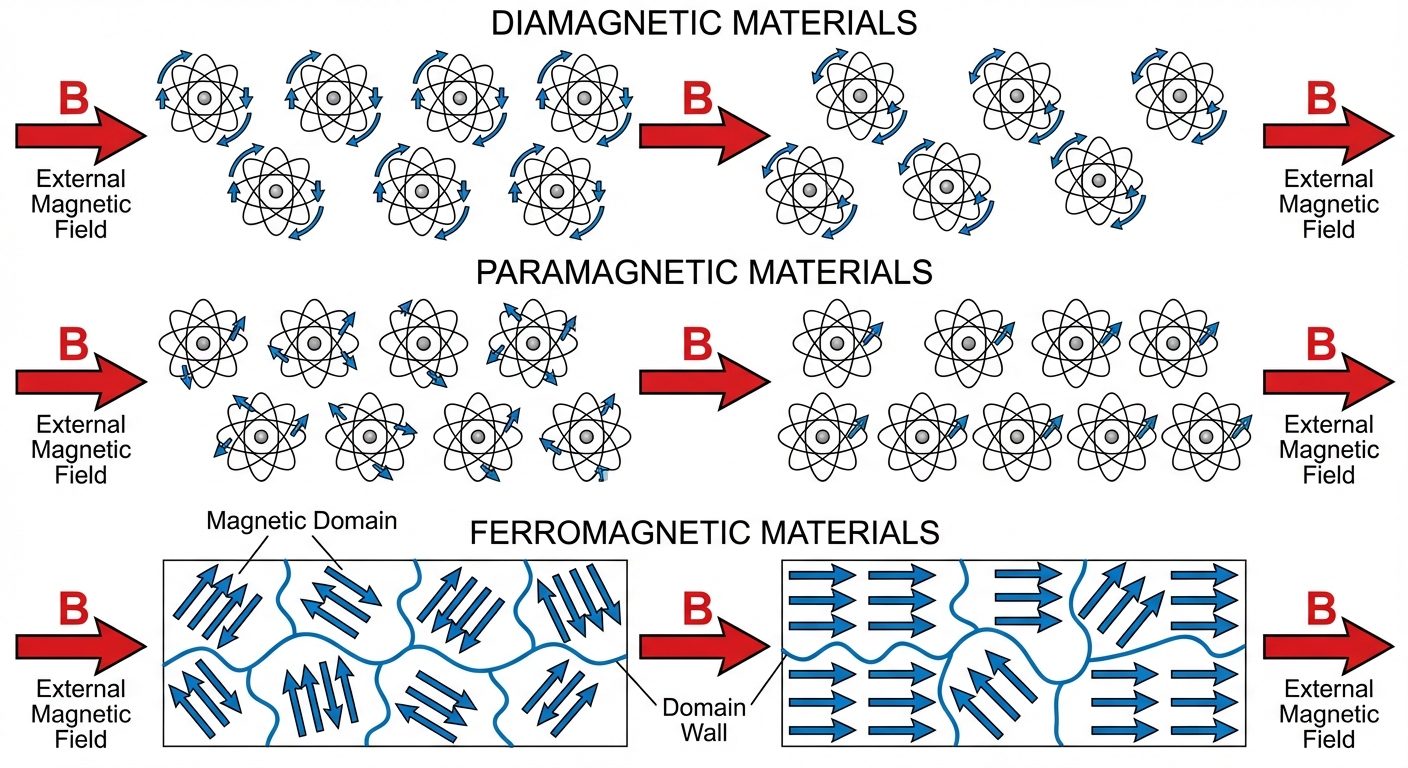

A. Diamagnetic Materials

Materials that create an induced magnetic field in a direction opposite to an externally applied magnetic field.

- Behavior: They are weakly repelled by magnetic fields.

- Atomic Origin: Arises from the orbital motion of electrons; present in all materials but often masked by stronger effects.

- Properties:

- Susceptibility () is small and negative ().

- Relative permeability .

- Independent of temperature.

- Examples: Bismuth, Copper, Gold, Water, Superconductors.

B. Paramagnetic Materials

Materials that form an internal, induced magnetic field in the same direction as the applied magnetic field.

- Behavior: They are weakly attracted by magnetic fields.

- Atomic Origin: Due to unpaired electrons causing permanent magnetic dipoles. Thermal agitation randomizes alignment.

- Properties:

- Susceptibility () is small and positive.

- Relative permeability .

- Susceptibility is inversely proportional to temperature (Curie’s Law: ).

- Examples: Aluminum, Platinum, Oxygen, Manganese.

C. Ferromagnetic Materials

Materials that exhibit strong magnetism in the same direction as the applied field and retain magnetism after the field is removed.

- Behavior: Strongly attracted to magnets.

- Atomic Origin: Due to "Exchange Interaction" resulting in parallel alignment of dipoles within regions called Magnetic Domains.

- Properties:

- Susceptibility () is very large and positive.

- Relative permeability (can be thousands).

- Exhibits Hysteresis (lagging of magnetization behind the magnetizing field).

- Above a specific temperature called the Curie Temperature (), they become paramagnetic.

- Examples: Iron, Nickel, Cobalt, Gadolinium.

2.2 Magnetic Data Storage

Magnetic materials are foundational to data storage technologies (Hard Disk Drives - HDD, Magnetic Tape).

- Principle: Data is stored by magnetizing tiny ferromagnetic particles (domains) on the surface of a disk or tape.

- Mechanism:

- Write: An electromagnet (write head) generates a field that aligns the magnetic domains in specific directions.

- Binary Encoding: The orientation of the domains represents binary data ($0$ or $1$). For example, North-South orientation might represent '1' and South-North '0'.

- Read: As the magnetized medium passes under a read head (often using Giant Magnetoresistance - GMR), the changing magnetic field induces a current (or changes resistance) which is interpreted as data.

- Material Requirement: Materials must have high Retentivity (ability to stay magnetized) and high Coercivity (resistance to demagnetization) to ensure data permanence.

3. Piezoelectric Materials

Piezoelectricity is the electric charge that accumulates in certain solid materials in response to applied mechanical stress. The word is derived from the Greek piezein, which means to squeeze or press.

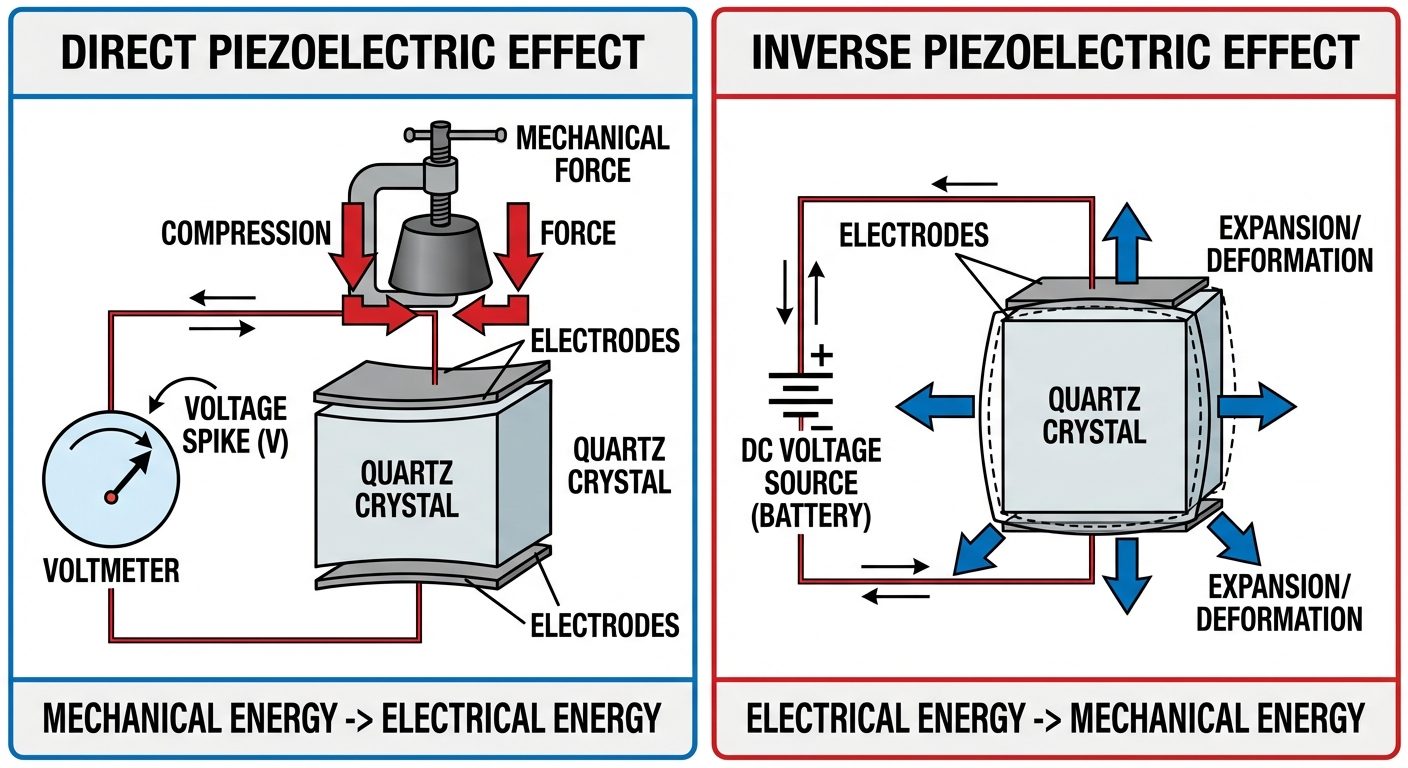

3.1 Direct Piezoelectric Effect

- Definition: The generation of an electric potential difference (voltage) across a material when it is subjected to mechanical stress (compression or tension).

- Mechanism: Mechanical deformation displaces the positive and negative charge centers within the crystal lattice, creating an electric dipole moment.

- Applications:

- Gas lighters (spark generation).

- Sensors (pressure sensors, accelerometers).

- Microphones (sound waves compress crystal electrical signal).

3.2 Inverse Piezoelectric Effect

- Definition: The mechanical deformation (change in shape/dimensions) of a material when an electric field is applied across it.

- Mechanism: Applying a voltage realigns the internal dipoles, causing the crystal lattice to expand or contract depending on the polarity of the field.

- Applications:

- Quartz watches (electric field keeps crystal vibrating at precise frequency).

- Piezoelectric actuators (ultra-precise positioning).

- Ultrasonic transducers (electrical signal mechanical vibration sound waves).

Common Materials: Quartz (), Rochelle Salt, Barium Titanate (), PZT (Lead Zirconate Titanate).

4. Superconducting Materials

4.1 Definition

Superconductivity is a phenomenon occurring in certain materials at extremely low temperatures, characterized by exactly zero electrical resistance and the expulsion of magnetic flux fields.

4.2 Key Properties

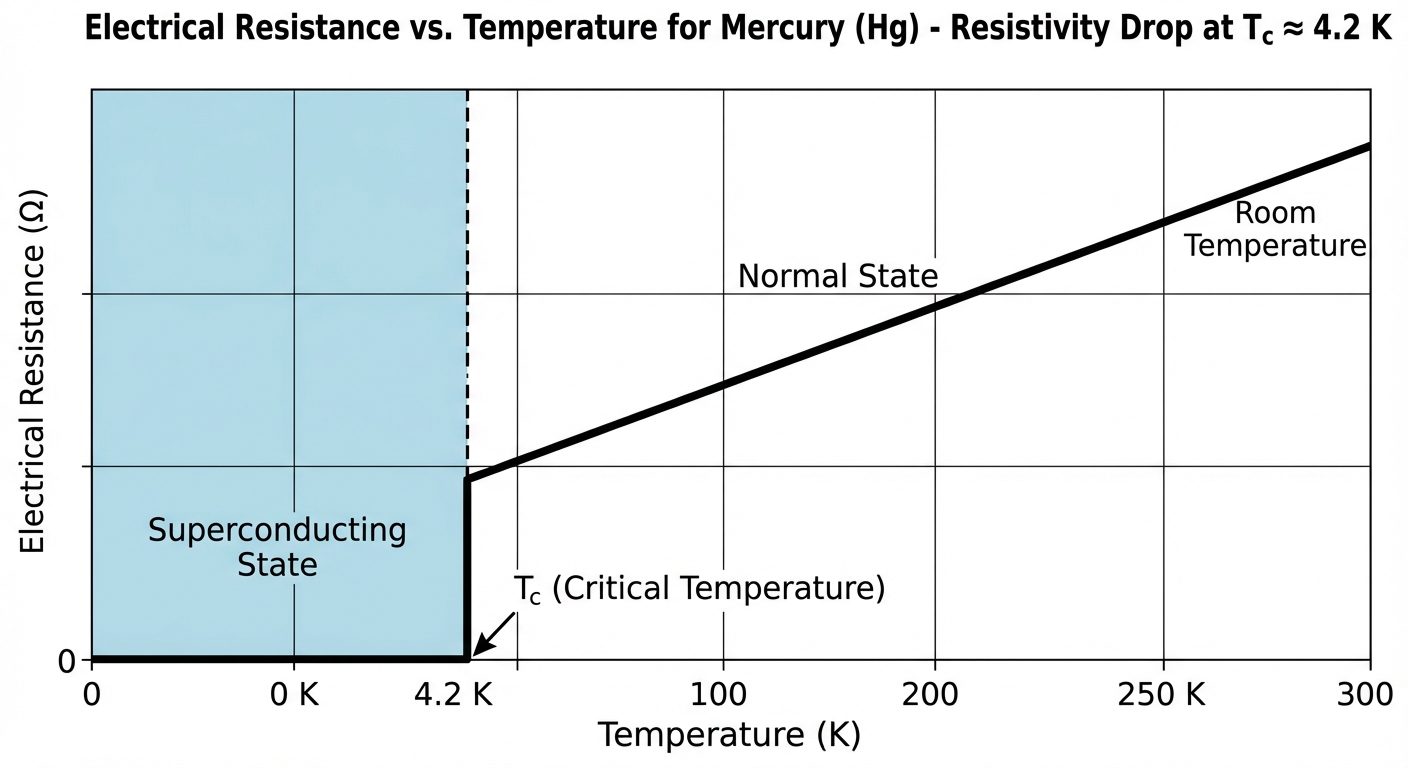

- Zero Electrical Resistance: Below the Critical Temperature (), the DC resistance becomes zero. Current can flow indefinitely without energy loss.

- Critical Temperature (): The specific temperature at which the material transitions from a normal conductor to a superconductor.

- Critical Magnetic Field (): A strong external magnetic field can destroy superconductivity, even below . The minimum field required to destroy the superconducting state is .

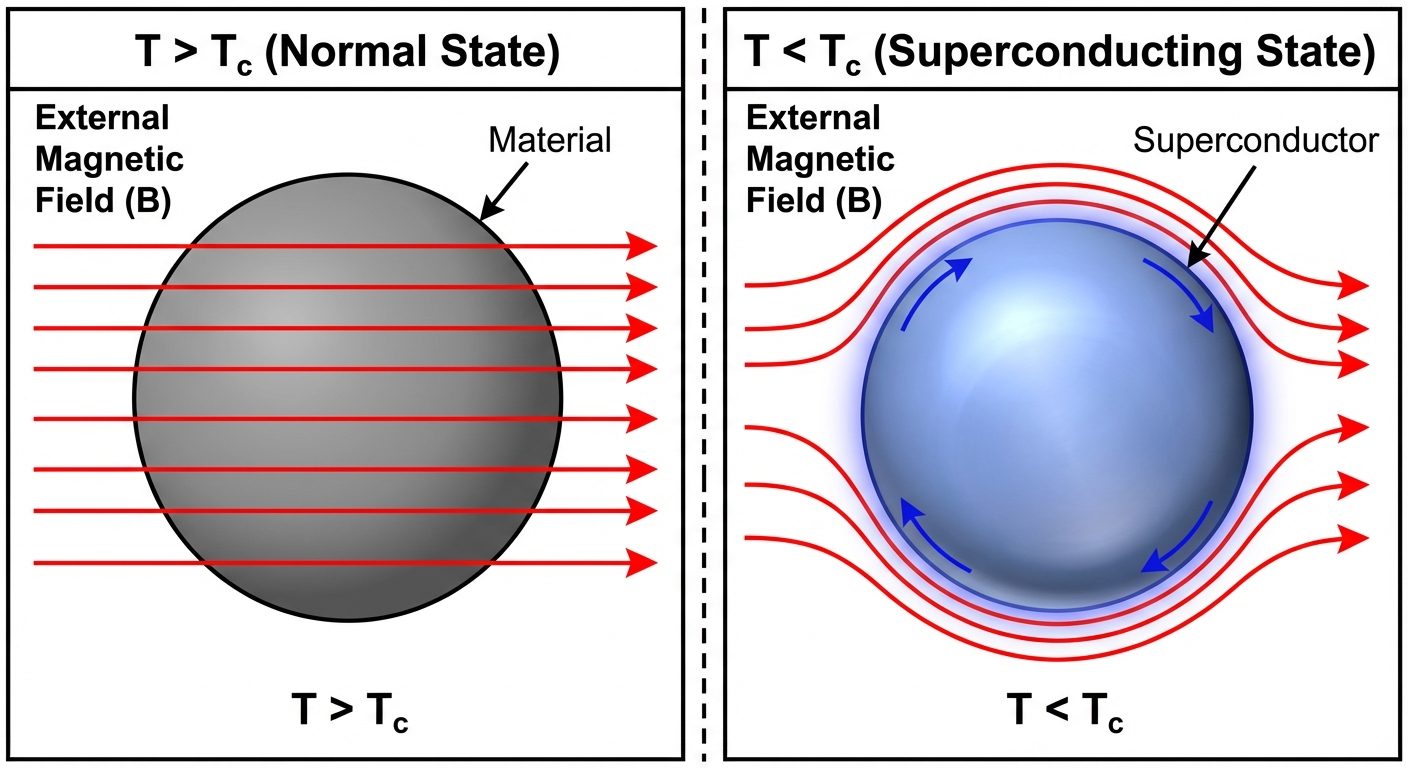

4.3 The Meissner Effect

The Meissner effect is the expulsion of a magnetic field from the interior of a material during its transition to the superconducting state.

- Perfect Diamagnetism: Inside a superconductor, the magnetic field .

- Susceptibility: .

- This proves superconductivity is a thermodynamic state, not just perfect conductivity.

4.4 Type I and Type II Superconductors

| Feature | Type I (Soft Superconductors) | Type II (Hard Superconductors) |

|---|---|---|

| Transition | Exhibits a sudden, sharp loss of superconductivity at Critical Field . | Loses superconductivity gradually between Lower Critical Field () and Upper Critical Field (). |

| Meissner Effect | Follows Meissner effect strictly (perfect diamagnetism). | Follows Meissner effect only up to ; between and , field lines penetrate in "vortices" (Mixed State). |

| Examples | Pure metals (Lead, Mercury, Tin). | Alloys and Compounds (Nb-Ti, ). |

| Practical Use | Limited (low values make them unfit for high-field magnets). | High (retain superconductivity in strong fields; used in MRI). |

4.5 Applications of Superconductors

- MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Uses Type II superconducting solenoids to generate massive, stable magnetic fields for medical imaging.

- Maglev Trains: Utilizes the Meissner effect (magnetic levitation) to float trains above tracks, eliminating friction and allowing high speeds.

- SQUIDs (Superconducting QUantum Interference Devices): extremely sensitive magnetometers used to detect subtle magnetic fields (e.g., brain activity).

- Power Transmission: Lossless transmission cables could revolutionize energy grids (currently limited by cooling costs).

- Particle Accelerators: Used in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) to steer particle beams.