Unit 6 - Notes

Unit 6: NoSQL Databases

1. Introduction: SQL vs NoSQL

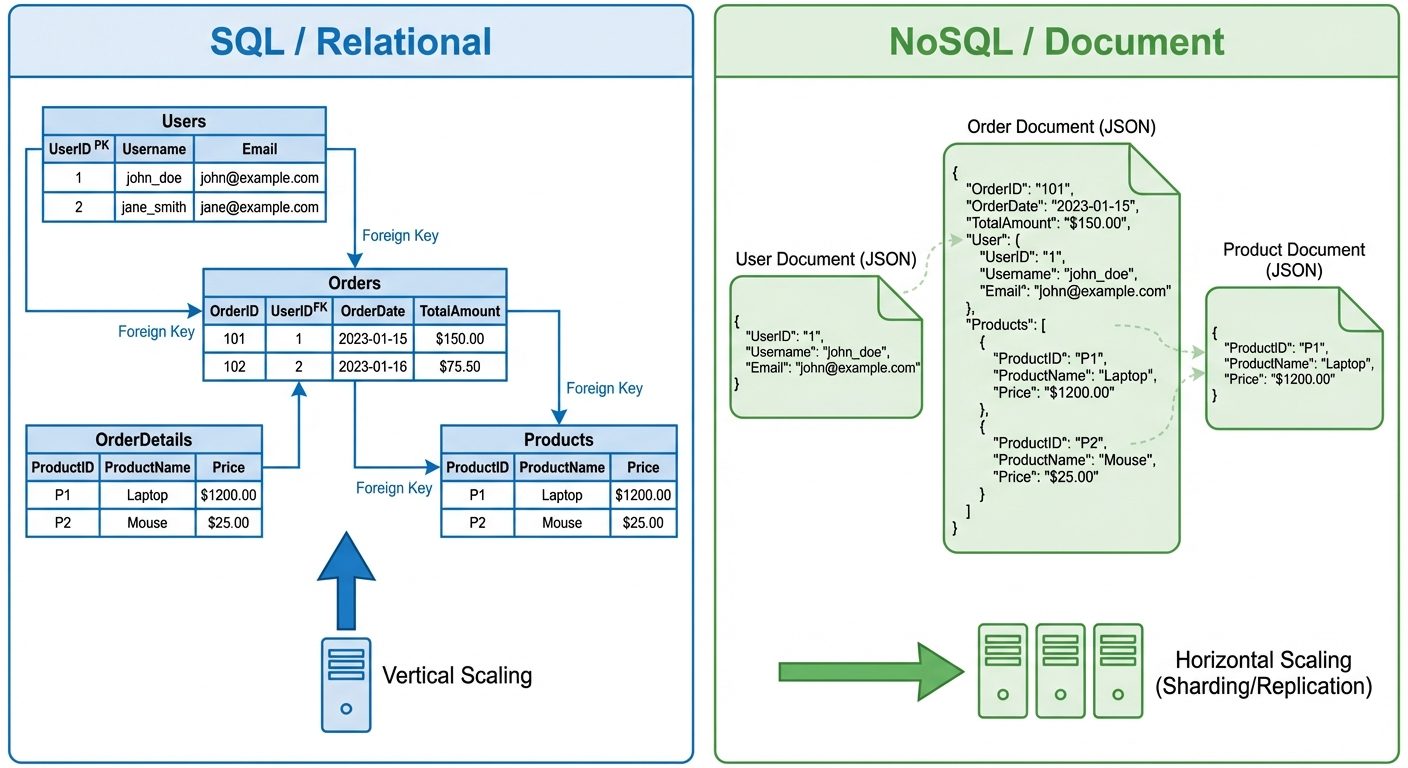

The transition from RDBMS (Relational Database Management Systems) to NoSQL (Not Only SQL) represents a shift from rigid, schema-based storage to flexible, scalable data management designed for modern web-scale applications.

Key Differences

| Feature | SQL (Relational) | NoSQL (Non-Relational) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Structure | Table-based with Rows and Columns. | Document, Key-Value, Wide-Column, or Graph-based. |

| Schema | Pre-defined (Static). Schema must be altered before inserting new data types. | Dynamic (Schemaless). Fields can be added on the fly; documents in the same collection can differ. |

| Scalability | Vertical Scaling (Scale Up): Increasing RAM/CPU of a single server. | Horizontal Scaling (Scale Out): Adding more servers (Sharding) to distribute load. |

| Relationships | Uses JOINs to connect tables. | Data is usually denormalized (embedded) or linked via references (no native complex JOINs). |

| Transactions | ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) compliance is standard. | Often follows BASE (Basically Available, Soft state, Eventual consistency), though many now support ACID. |

2. Introduction to MongoDB & Structure

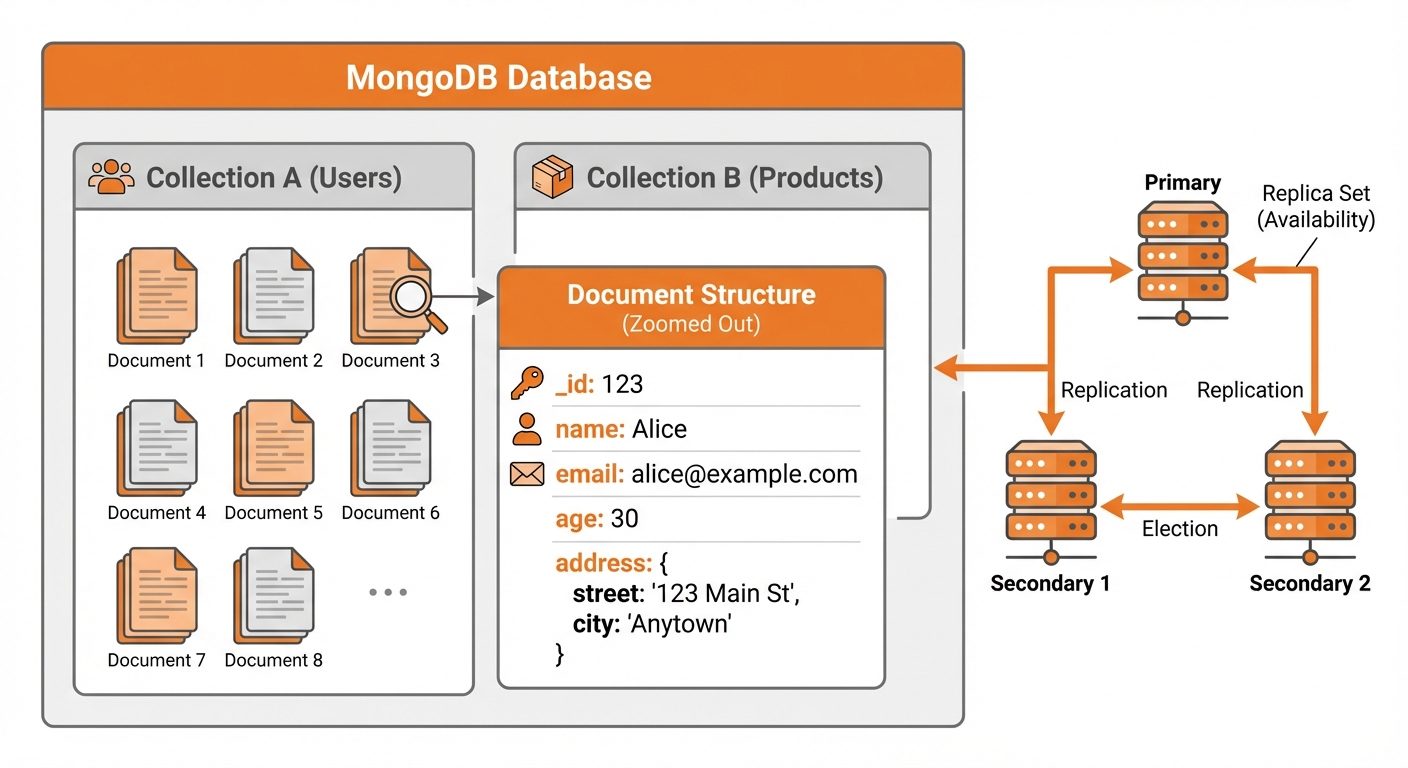

MongoDB is the most popular document-oriented NoSQL database. It is open-source and provides high performance, high availability, and automatic scaling.

Core Concepts and Hierarchy

- Database: A physical container for collections. A single MongoDB server can hold multiple databases.

- Collection: A group of MongoDB documents. This is the equivalent of an RDBMS "Table". It does not enforce a schema.

- Document: A set of key-value pairs. This is the equivalent of an RDBMS "Row". Documents utilize BSON (Binary JSON) format.

- Field: A key-value pair in a document. Equivalent to a "Column".

BSON (Binary JSON)

While MongoDB allows developers to work with JSON, it stores data internally as BSON.

- Efficiency: BSON is designed to be efficient for storage and scanning speed.

- Data Types: BSON supports types not found in standard JSON, such as

Date,ObjectId(primary key), and rawBinarydata.

Architecture Features

- Replica Sets: Multiple copies of data on different servers to ensure high availability and redundancy. If the primary node fails, a secondary node automatically becomes primary.

- Sharding: The process of storing data records across multiple machines. It is MongoDB's approach to meeting the demands of data growth (Horizontal Scaling).

3. DynamoDB & Serverless Cloud Databases

Amazon DynamoDB

DynamoDB is a fully managed, proprietary NoSQL database service provided by Amazon Web Services (AWS).

- Type: Key-Value and Document store.

- Architecture: It runs on AWS infrastructure and automatically distributes data and traffic over a sufficient number of servers.

- Performance: It delivers single-digit millisecond performance at any scale. It uses SSDs solely.

Serverless Cloud Databases

"Serverless" does not mean there are no servers; it means the developer does not have to manage them.

- Auto-scaling: The database automatically scales up or down based on request volume (throughput).

- Pay-per-use: You are charged based on the read/write capacity units consumed, not for a fixed server size.

- Zero Administration: No need to patch OS, install software, or configure replication manually.

- Examples: AWS DynamoDB, Google Cloud Firestore, Azure Cosmos DB.

4. JSON Databases & Representation

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is a lightweight data-interchange format. It is easy for humans to read and write and easy for machines to parse and generate.

JSON Syntax Rules

- Data is in name/value pairs (

"name": "value"). - Data is separated by commas.

- Curly braces

{}hold objects. - Square brackets

[]hold arrays.

JSON Representation of a Dataset

Below is a representation of an E-commerce dataset. Note the Embedding (Denormalization) where the address and orders are stored inside the user document, rather than in separate tables.

{

"_id": "507f1f77bcf86cd799439011",

"username": "john_doe",

"email": "john@example.com",

"is_active": true,

"roles": ["customer", "subscriber"],

"contact_details": {

"phone": "555-0199",

"address": {

"street": "123 Main St",

"city": "Metropolis",

"zip": "10012"

}

},

"recent_orders": [

{

"order_id": "ORD-999",

"total": 45.50,

"items": [

{"product": "Wireless Mouse", "qty": 1},

{"product": "Battery Pack", "qty": 2}

],

"status": "delivered"

}

],

"joined_date": "2023-10-15T14:30:00Z"

}

5. Working with MongoDB (CRUD Operations)

Interaction with MongoDB is primarily done through the MongoDB Shell (mongosh) or drivers (Python, Node.js, Java).

1. Create (Insert)

Adding new documents to a collection.

// Insert a single document

db.users.insertOne({ name: "Alice", age: 25, city: "NYC" });

// Insert multiple documents

db.users.insertMany([

{ name: "Bob", age: 30 },

{ name: "Charlie", age: 35 }

]);

2. Read (Query)

Retrieving data using find().

// Find all documents

db.users.find();

// Find with filter (WHERE name = 'Alice')

db.users.find({ name: "Alice" });

// Comparison Operators: Find age > 26

// $gt = Greater Than, $lt = Less Than, $eq = Equal

db.users.find({ age: { $gt: 26 } });

3. Update

Modifying existing documents.

// Update the first matching document

// Uses Atomic Operators like $set to modify specific fields

db.users.updateOne(

{ name: "Bob" }, // Filter

{ $set: { age: 31 } } // Update Action

);

4. Delete

Removing documents.

// Delete all users named Charlie

db.users.deleteMany({ name: "Charlie" });

6. Index Creation & Performance Comparison using EXPLAIN

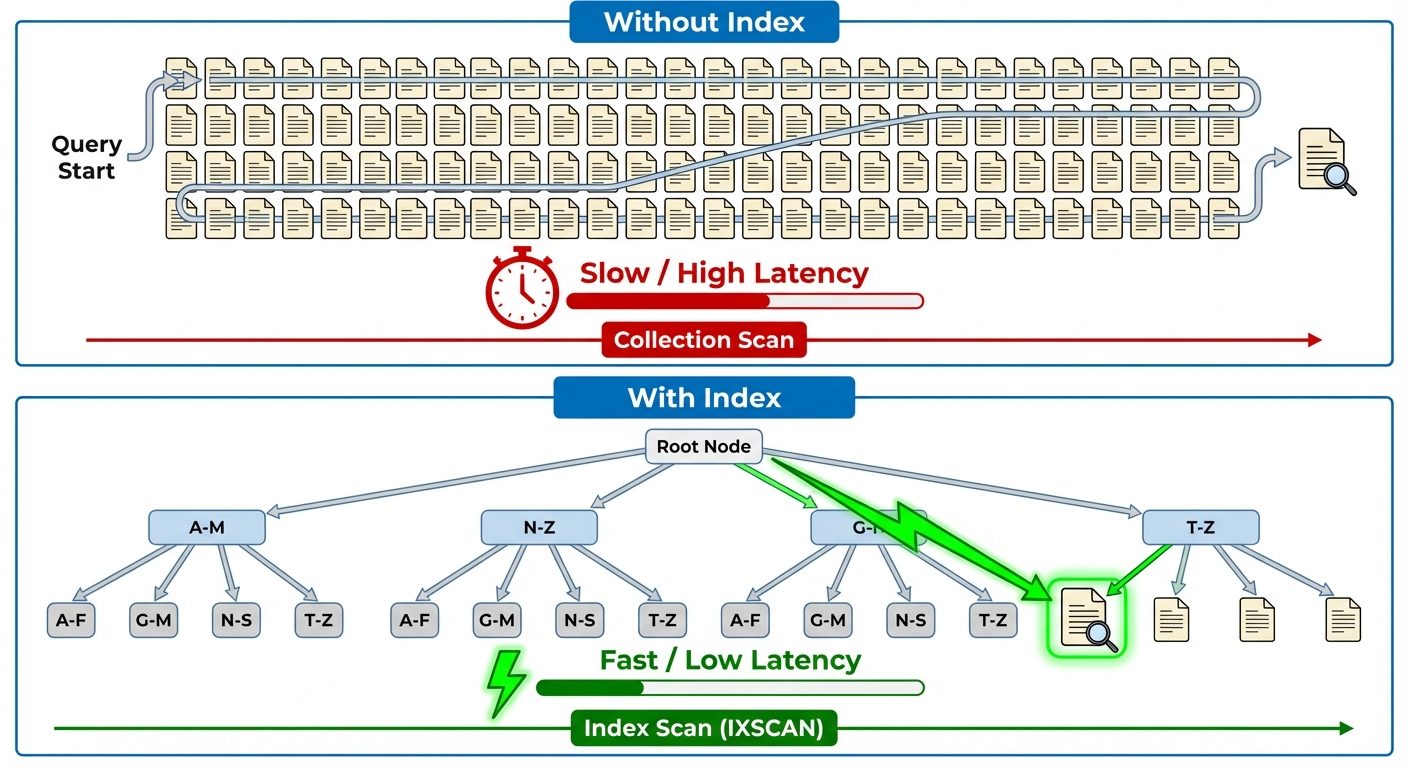

In NoSQL, just like in SQL, indexes are crucial for performance. Without an index, MongoDB must perform a Collection Scan (scan every document) to find query matches.

Creating an Index

Indexes are created on specific fields to support queries.

// Create an index on the 'username' field (1 for ascending order)

db.users.createIndex({ username: 1 });

The EXPLAIN Command

The explain() method provides details on the execution plan of a query. It tells you whether the query used an index or scanned the whole collection.

Syntax:

db.users.find({ username: "john_doe" }).explain("executionStats");

Performance Comparison

| Metric | Without Index (COLLSCAN) | With Index (IXSCAN) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage | COLLSCAN (Collection Scan) |

IXSCAN (Index Scan) |

| totalDocsExamined | High (e.g., 1,000,000 if 1M docs exist) | Low (e.g., 1 - specific match) |

| nReturned | 1 | 1 |

| executionTimeMillis | High (e.g., 500ms) | Low (e.g., 2ms) |

Interpretation:

- COLLSCAN: The engine had to read every document in memory to check if it matched. Very slow for large datasets.

- IXSCAN: The engine used the B-Tree index to jump directly to the record. Very fast.

7. Vector Databases

Vector databases have emerged as a critical component of the modern AI/ML stack, distinct from standard NoSQL document stores.

Concept

Traditional databases query for exact matches (e.g., "Find user where ID = 5"). Vector databases are designed to store and query Vector Embeddings.

- Embeddings: High-dimensional arrays of numbers (vectors) generated by AI models (like GPT-4 or BERT) that represent the semantic meaning of text, images, or audio.

How it Works

- Vectorization: Raw data (text/image) is converted into a vector (e.g.,

[0.1, -0.5, 0.8, ...]). - Storage: The database stores this vector.

- Similarity Search: When a user queries, the query is converted to a vector. The database searches for vectors that are mathematically "closest" to the query vector using algorithms like Cosine Similarity or Euclidean Distance.

Use Cases

- Semantic Search: Searching for "Something to sit on" returns "Chair" even if the word "sit" isn't in the product description.

- Recommendation Systems: Finding items with similar feature vectors.

- GenAI Context (RAG): Providing relevant long-term memory to LLMs (Large Language Models).

Popular Vector Databases

- Pinecone (Native Vector DB)

- Milvus (Open Source)

- MongoDB Atlas Vector Search (NoSQL + Vector capabilities)